Michigan State University Press

By REESE CARLSON

Capital News Service

LANSING – Jane Elder once escorted a live cormorant to a congressional hearing.

Elder, then a Sierra Club lobbyist, and James Ludwig, a Great Lakes ecologist, drove the bird named Cosmos from the Upper Peninsula to Washington in 1989.

Cosmos had a beak deformity, and the two brought her into the hearing to show lawmakers proof of the effects of toxic air pollution.

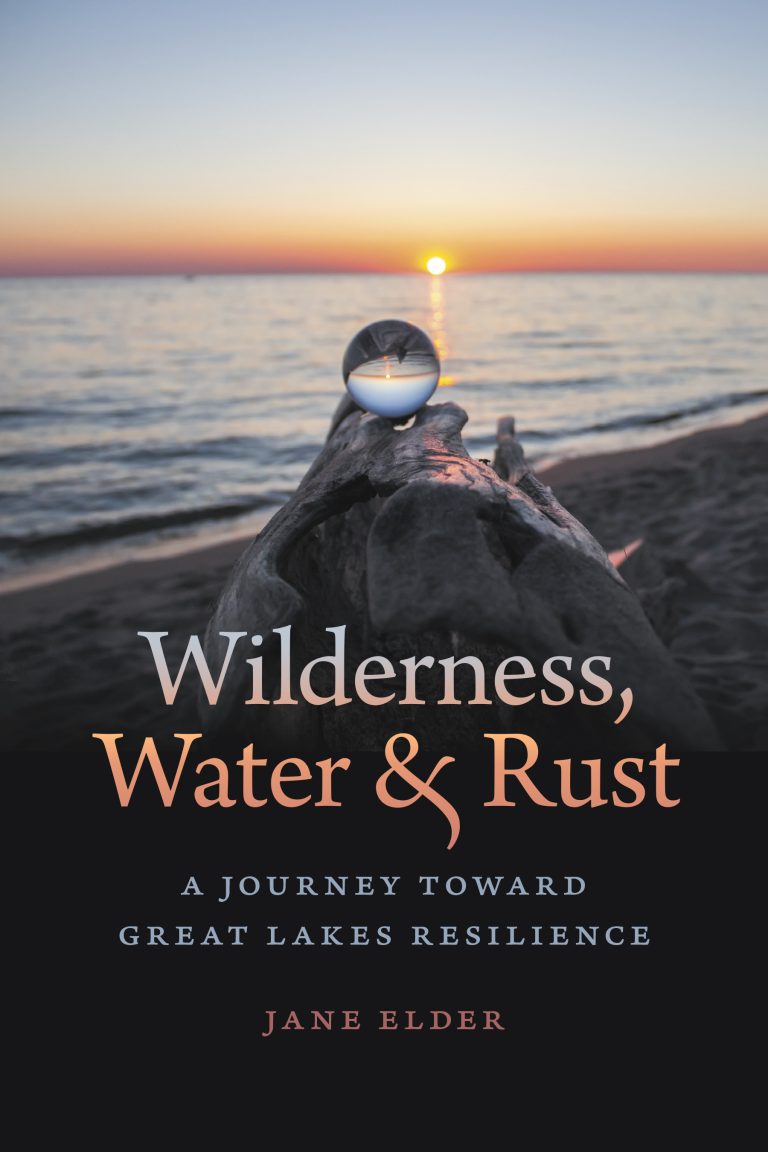

Elder features other similar moments in her new book, Wilderness, Water & Rust: A Journey toward Great Lakes Resilience (Michigan State University Press, $39.95).

She once brought water pollution to the forefront of many politicians’ eyes when she provided them with a buffet of fish no one could eat because they were highly contaminated.

The book is a memoir of 50 years in environmental advocacy and leadership, including serving as a lobbyist and then director of Michigan’s chapter of the Sierra Club, as a consultant and as the executive director of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts & Letters.

It is also a policy critique of what has been accomplished in the Great Lakes region regarding ecological resilience, an ecosystem’s ability to maintain its normal patterns when experiencing disturbances.

“When talking about resilience, it is everything from water quality pollution control to biological diversity to physical protection of the habitat that all weaves into what makes a system resilient,” Elder said.

The region can be resilient but is inhibited by many human factors, Elder said. Humans need to put in the work to help the ecosystem become resilient once more.

The 311-page book is riddled with bits and pieces of Elder’s experiences in the natural world. She tells readers about her part in establishing Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore and Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, helping find the money to create those new parks.

“I worked on the early stages of the national lakeshores: Pictured Rocks, Sleeping Bear Dunes, Indiana Dunes,” Elder said. “They had all been established in the 1960s or the 1970s, but getting the money to create a new national park is a story that a lot of people don’t know when they’re standing on the beautiful dunes looking out at the lake.”

The book offers a glimpse of growing up in a world with few environmental protections. Scientists would publish their findings on the effects of air pollution or water pollution and no one would believe them, Elder said.

One section focuses on land and another on water. Another is about treasured wilderness areas and our connections with these places that require protections.

“Jane has been such an influential person in the realm of environmentalism for years and years,” said Anne Woiwode, Elder’s longtime friend and a former director of the Sierra Club’s Michigan chapter. “She was one of the first people working in the environmental arena to focus on the Great Lakes as a place that needed significant attention.”

And she had a flair for attracting attention to a specific issue, Woiwode said.

“She wanted to make sure that Congress knew about pollution in Great Lakes fish,” Woiwode said.

“So, she put on a buffet for Congress that included all of those polluted Great Lakes fish. This was a great way to put the issues right in front of people. When you can visualize what is happening – this is the level of expected contamination in this fish – it really brings it home,” Woiwode said.

Elder made the fish look pretty, complete with lemons, and large signs reading “DO NOT EAT, POLLUTED FISH” in bright red lettering.

Most of the sections are based on her journal entries, Elder said.

“When something that felt important happened to me, I would write down how I felt and how I experienced it,” she said.

With nearly 50 years of environmental advocacy under her belt, Elder has many journal entries worth sharing. She says she hopes they offer lessons in leadership for the younger generations and their battles in environmental advocacy.

That seems likely, Woiwode said. It wasn’t just policy that Elder influenced. She also had a significant impact on the people who worked for change.

“She was my personal mentor and was a mentor to many environmental leaders in this region,” Woiwode said. “You look for people to be heroes, and she is one of those sorts of people, but she also made sure other people could be heroes as well.”

Reese Carlson writes for Great Lakes Echo.

Schoolcraft Tourism & Commerce

The 26-mile Pine Marten Run Trail is in the Hiawatha National Forest’s Ironjaw Semi-Primitive Area. Credit.