State Police

Col. James Grady II is the director of the State Police.By ALEX WALTERS

Capital News Service

LANSING – The State Police is struggling to diversify as its new academy classes continue to be whiter than the department’s overall force and the people of the state it polices.

“We have some work to do,” State Police Director Col. James Grady II said. “I’m not happy with the current demographics of the agency.”

State Police officers are 90% white, according to the latest department data.

Michigan’s population is 74% white, the most recent census data shows.

At this point, the department doesn’t seem to be trending towards a more diverse future.

Of the last 10 academy classes, held between 2018 and 2023, five were whiter than the force overall, according to the data.

Grady said he believes a large part of the problem is a negative perception of law enforcement due to police brutality incidents, like the 2020 murder of George Floyd, going viral on social media.

Floyd, an unarmed Black man, was slain by a white Minneapolis police officer who knelt on his neck for more than nine minutes. The officer was convicted of murder and other charges.

“Sometimes I feel it’s a little unfair,” Grady said. “Most law enforcement officers and state troopers are doing the right thing every day. I’ve never done anything like what you saw with George Floyd. I’ve been in the profession for 25 years, and I’ve never seen anybody do that in my presence.”

That negative perception of the police deters people of color from seeking positions as State Police troopers, Grady said.

“People see 30 seconds of a video and they go, ‘OK, well police officers are bad,’” Grady said. “Well, what about the other four and a half minutes of that video that you didn’t see? I always tell people to wait until you see it all before you pass judgment.”

In hopes of changing that perception, Grady has tasked recruiters with spending more in-person time in communities of color.

“We gotta let people know we want them,” Grady said.

The department has been hosting sessions across the state where potential applicants can take entrance exams and fill out applications, said Brian Buege, the commander of the department’s Recruiting and Selection Section.

“We’re finding that by going there and actually having face-to-face interaction with candidates, we’re able to answer their questions and make a real personal connection,” he said.

The department is also attempting to provide more support to applicants.

The State Police’s application and training process is much more demanding than that of most local agencies, said Ann Ryan, an organizational psychology researcher at Michigan State University who studies law enforcement recruitment.

After a candidate passes the written exam and submits an application, they have to pass a hiring interview, a physical fitness test, a background investigation, a medical examination and a psychological evaluation.

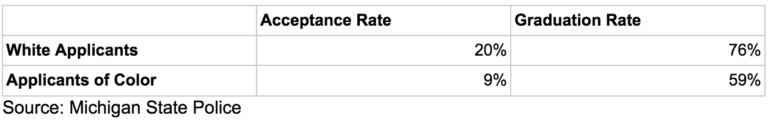

White applicants have been favored by that process, according to department data. In the last 10 academy classes, the acceptance rate for white applicants was 11% higher than that of applicants of color.

The department is looking to close that gap.

It has mandated implicit bias training for interviewers and is attempting to narrow socioeconomic gaps by providing laptop computers to applicants, Buege said.

Some barriers however are out of the department’s control, he said. For example, the entrance exam is created and regulated by the Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards.

The retention challenges don’t stop once applicants begin the academy.

When the current State Police recruit class began less than a month ago, it had 73 cadets. Today, only 57 remain, Buege said.

That’s nothing new. He said the first weeks of the academy lose the most people.

The racial disparities also contribute to that attrition.

In the last 10 classes, white recruits graduated at a rate 17% higher than their peers of color, the data shows.

Ryan, the psychologist, said negative perceptions of law enforcement aren’t a factor in the dropout rate. Rather, she said, she believes the lower graduation rate is a product of barriers recruits face during training.

“Those are people who have gone through the whole application process,” Ryan said. “They’re interested in the job, they want the job, they’re making a commitment to it. For them, it’s a different set of things.”

The department is working to lower the overall drop-out rate by offering training and information sessions to applicants before they begin the intense, residential academy program.

The academy has started offering sessions on fitness and legal knowledge. It also offers overnight stays at the academy before recruit school starts to familiarize candidates with the facilities and instructors ahead of training, Buege said.

“We’re trying a new holistic approach to recruiting to best prepare candidates for success in the recruit school,” he said. “We want to expose them to what to expect.”

State Police

The proportion of white and non-white State Police Academy applicants and their academy graduation rates