Committee to Protect Journalists

Kazakhstan journalist Diana Saparkyzy of the independent news agency KazTAG was assaulted while covering a coal mining disaster.By ERIC FREEDMAN

Capital News Service

LANSING – Reporting on environmental problems and controversies remains a perilous endeavor, as demonstrated by a series of incidents around the globe.

Journalists are physically assaulted, jailed, interrogated by police, kidnapped, fired, sued for libel, harassed and even murdered for seeking to expose environmental crimes, corruption and misconduct by powerful government, military and business interests.

I recently interviewed Diana Saparkyzy of the independent news agency KazTAG in Kazakhstan who was assaulted while reporting on a fatal mining accident last summer.

The incident happened after a fire at a coal mine owned by a subsidiary of a multinational steel manufacturer based in Luxembourg. More than 220 miners were safely evacuated, but five remained underground when Saparkyzy arrived on the scene.

The company refused to release information about the dead men or provide their photos to the journalists who gathered there.

Saparkyzy told me, “I came to the mine and there were guards. They asked, ‘Young woman, who are you?’ I said I was a miner’s relative because if I said I was a journalist they wouldn’t let me inside. Then the company’s PR managers went into the office and saw me and were shocked.”

The guards seized Saparkyzy as she was recording the incident on her iPhone, and a guard who was deleting her videos didn’t realize it was still recording. She grabbed the phone, restored the deleted videos from its trash bin and immediately sent it to her editors who “put it on the website nonstop.”

How did Saparkyzy feel at the time? “I was in shock. I was very scared. It was the first time in my life I was attacked by a group of guys, and they were big. During the investigation, my lawyer and I found out they were former prison guards.”

For more than 20 years, I’ve been privileged to interview and train journalists, journalism educators and press rights defenders on six continents, many of them working – or trying to work – in some of the world’s most corrupt, dangerous and repressitarian countries.

Thus it’s no surprise that environmental journalism has been called one of the world’s most dangerous beats.

That’s because our work and mission challenge powerful industries, institutions and people. Many are in extractive industries such as logging, oil drilling, fishing and mining. Many operate polluting factories.

It’s greed, pure and simple with huge amounts of money and political and economic clout at stake.

Many victims of environmental injustice are the powerless, often in poor urban and rural areas or Indigenous regions far from media scrutiny. Their communities lack political influence and financial resources to effectively challenge those in power.

I admire environmental journalists’ bravery and commitment to mission.

One of them is Liberian independent newspaper editor Rodney Seih, who spent three months in his country’s most notorious prison because of an unpaid $1.5 million fine for a libel conviction. His so-called crime? Exposing a former Cabinet minister’s involvement with a corrupt financing scheme for treating an infectious parasite killing farm crops.

Seih told me: “Most media houses are strangled by the (Liberian) government because the government is a big advertiser in paying media. They strangle you so you become a slave to them. It deprives you from really doing what you want to do in covering these environmental stories, these political stories that affect people.”

Sam Cowie, a British freelancer based in Brazil, covers environmental issues in the Amazon.

Cowie described his encounter with illegal gold miners when he and a photographer were reporting on ecologically damaging mining activities in the northern part of the country.

On their arrival at the miners’ encampment. “it quickly transpired we weren’t welcome.”

“There were indirect and fairly explicit threats. People were telling us, ‘We all know who you are and what you’re doing here,” he recalled. The crowd told them ominously, “People disappear here all the time. People get shot and killed here all the time.”

Spine-chilling is the degree of intimidation that some corporations and their lawyers wield, with the open or unspoken support of government officials. Cowie said, “They don’t need a hitman to kill you. They can send their lawyer to crush you.”

Tragically, these aren’t isolated stories. The roster of attacks and threats in 2023 includes the arrest and detention of a Venezuelan journalist covering illegal gold mining and the kidnapping of a Bangladeshi journalist while reporting on illegal brickyard operations.

It’s by no means a problem only in developing countries. U.S., Canadian and European journalists are targeted too.

Here’s an account of corporate influence from independent journalist Tsira Gvasalia in the Republic of Georgia.

In her investigation into misdeeds by the country’s only gold mining company, she was unable to get information from the local prosecutor, from the agency with environmental responsibilities and from courts. “The company has a close connection with the government,” she told me. Ordinary citizens aren’t always willing to talk to the press under such circumstances.

When the project began, she visited the small town where the mining took place. Covering roadways and bus stops were thick layers of dust from uncovered trucks carrying ore to the mining company’s processing facility.

When she asked residents how the pollution affected their everyday lives, people were “very careful. Once I mentioned the name of the company, everybody went silent. Everyone worked for the company,” Gvasalia said. Only later did residents become “more open, more daring to speak of it.”

In the U.S.environmental reporter Tim Wheeler is the associate editor of a nonprofit magazine that reports on the Chesapeake Bay watershed in parts of six states and Washington, D.C.

His investigation of environmental violations at a scrapyard near Baltimore Harbor revealed a state agency’s loose enforcement and lack of vigilance. The scrapyard owner sued him and the magazine for defamation.

Wheeler told me the lawsuit “didn’t allege any (reporting) errors” but claimed the company was “cast in an unfavorable and false light.” The case dragged on for three years.

Elsewhere last year, a British journalist and documentary maker was arrested while covering an environmental protest during the coronation of King Charles III. An Albanian TV crew was threatened at gunpoint and a crew member was assaulted while using a drone to film an illegal mining operation.

Such attacks may discourage or deter watchdog environmental journalism and may prevent disclosure of public health hazards, corruption and incompetence.

Many journalists I’ve interviewed said their experiences reinforced their sense of mission, however.

Saparkyzy, the Kazakh journalist, said, “This situation hardened me and made me more stable in the face of stress. When I was under pressure, it got on my nerves. I had some kind of psychosis and wanted to give up at some point, but then I got my things together and decided to go till the end.”

But other targeted journalists choose to go into exile, change careers or both – a loss to the profession and the loss of expertise in covering the environment. They also describe psychological problems, especially post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and fear of another arrest, another attack, another threat.

Some who stay in the profession have good reason to worry. A psychologist said they face the pressures of “living in very precarious situations” and knowing that the repressive regime in their home country remains in power.

So why do they persevere?

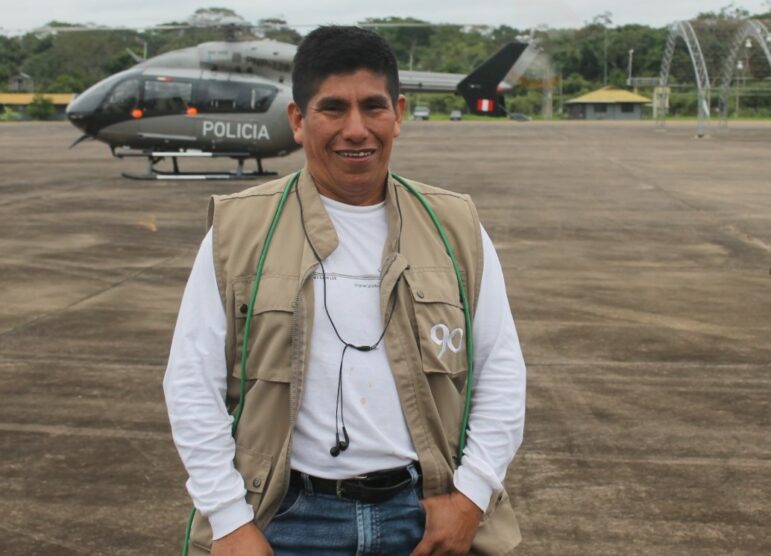

I asked Peruvian environmental journalist Manuel Calloquispe who, among other attacks, once had a machete thrown at him. He reports for a national television channel and newspaper, focusing on the black market, underground economy, gold mining and coca plantations.

While investigating illegal trafficking in fuel used for illegal mining, a company owner warned him that “very powerful people were behind these businesses.”

And when Calloquispe reported the incident to a Peruvian journalism group, he was advised to wear a bulletproof vest and helmet when he goes out. And he does.

He’s turned down job offers in Lima, the much safer capital.

Why does he stay?

Here’s his explanation: He’s seen the biodiversity of the place and the migrants who move to the region seeking new opportunities but are kidnapped, killed or enmeshed in illegal activities. He’s seen the damage from illegal mining to the forests, vast parts of which are becoming deserts or savannahs.

But perhaps the most compelling reason: “I decided that if I don’t do it, who else will do it?”

Eric Freedman is the director of Capital News Service.

Committee to Protect Journalists

Despite threats and attacks, Peruvian journalist Manuel Calloquispe continues to cover environmental controversies, saying, “I decided that if I don’t do it, who else will do it?”

Bay Journal

Tim Wheeler, the associate editor of Bay Journal, based in Maryland, was sued for reporting on environmental violations at a scrapyard near Chesapeake Bay.

Michigan State University