By KELSEY LESTER

Capital News Service

LANSING — Although perilous to native species of mussels, the invasive zebra and quagga mussels have made Michigan’s murky waters into a clear blue within the last three decades.

The word “invasive” sounds hostile, but in terms of filtering power, these mussels are able to clean water at a hyper-speed.

Expert “clammer” Joe Rathbun of Lansing has spent the majority of his life researching clams and mussels. Although retired, he still dedicates his time to the study of mussels.

“You know, they’re not Bengal tigers — they can’t even move — but it’s the little things that run the world,” Rathbun said.

Renee Mulcrone from Portage agreed.

Working as an aquatic biologist, Mulcrone first found her curiosity with clams working for the Illinois Natural History Survey’s research institute while going to the University of Illinois. After getting her doctorate from the University of Michigan, mussels still feed her passion.

“Little slimy things with no brains and no eyes need lovin’ too,” she said. “That’s our exotic species.”

“You can go to Africa and see the elephants or go down to South America and see all kinds of interesting wildlife. The mussels in North America are our unique species,” she said.

Michigan’s fresh waters are home to around 43 species of mussels. There are over 300 in the world.

Mussels, often referred to as clams, typically lay in or on the bottoms of lakes and rivers. While there is a biological difference between clams and mussels, the terms are used synonymously among researchers.

“Some of these (native) mussels can even reach 40 to 50 years old — they’ve seen a lot,” said Jo Latimore, who is an MSU aquatic ecologist and outreach specialist.

“They can’t tolerate a highly disturbed system or a highly polluted system, so I see them as indicators of how healthy or unhealthy a waterway is,” she said.

Because of their colonization, invasive mussel species are a concern for all clammers. While there are now around 30 mussel biologists in the state, Rathbun is one of only three to see what clam life was like before the invasion of zebra mussels in the 1980s.

Zebra mussels invaded Michigan’s Great Lakes in the 1980s because of contaminated water discharged from cargo ships’ ballast tanks.

Now, not only is Michigan home to trillions in the Great Lakes, but they’ve made 255 inland lakes their homes too, according to the Michigan Sea Grant.

Native populations have drastically decreased according to a Central Michigan University three-year study of the remaining populations in the St. Clair River and Detroit River.

“Bordering Lake St. Clair, we know that historically there were hundreds of thousands or more native mussels on the bottom of both those rivers. Millions probably. Now there are only dozens to hundreds in a few places — the rest have been wiped out by the zebra mussels,” he said.

Invasives blanket colonies of native mussels, so that surrounded mussels cannot feed or receive the bacteria they need to survive. Zebra mussels are even competitive with some game fish, like perch in Lake Michigan.

However, zebra mussel populations have been declining because of the quagga mussel, which arrived at the Great Lakes about a decade after zebra mussels and have shown to be even tougher.

That’s because quagga mussels can multiply without having to attach themselves to anything, meaning they can breed just about anywhere.

Fisheries biologist Thomas Goniea sits on the Department of Natural Resources mussel committee.

“Quagga mussels are zebra mussels on steroids,” Goniea said.

“There’s no comparing the environmental impacts of the two species. Most of the Great Lakes mussels that you see now are almost 100% quagga mussels,” he said.

Zebra mussels colonize the shallower portions of the Great Lakes, while quaggas can colonize the deepest depths.

The Center for Invasive Species Research at the University of California Riverside Campus says there were about 900 zebra mussels per square meter in Lake Michigan, but quagga mussels have reproduced up to eight times more and have been counted at around 8,000 per square meter.

“We’re a ways from seeing the final impacts of these things on the Great Lakes,” Goniea said.

However, some experts say the invasives could have benefits. That’s because of their immense power to filter waters.

Goniea said he walked away from a presentation on the invaders with something that’s stuck with him ever since.

“They measured the filtration rates of quagga mussels and how fast they could filter the water,” Goniea said. “Based on the filtration rates and the densities of those mussels, they said every drop of Lake Michigan water goes through a quagga mussel every 48 hours.”

Rathbun agreed.

“You could argue that zebra mussels almost don’t matter if you’re just thinking of filtering the water, improving its clarity and removing nutrients,” he said. “If all you’re interested in is mechanical filtration of water — zebra mussels do that at least as well as native mussels do.”

Goniea highlighted their impact and potential strength in Michigan’s ecosystem.

“Their impact in the ecosystem is unrivaled,” he said.

“What the Great Lakes looks like in five, 10, 15 years from now, unless something else comes in, is going to be determined by quagga mussels,” Goniea said.

“Based on what I’ve read, the impact of quagga mussels on the Great Lakes is only rivaled by the impact of the sun on the Great Lakes — that’s how powerful and how much of a keystone species they are in the system,” he said.

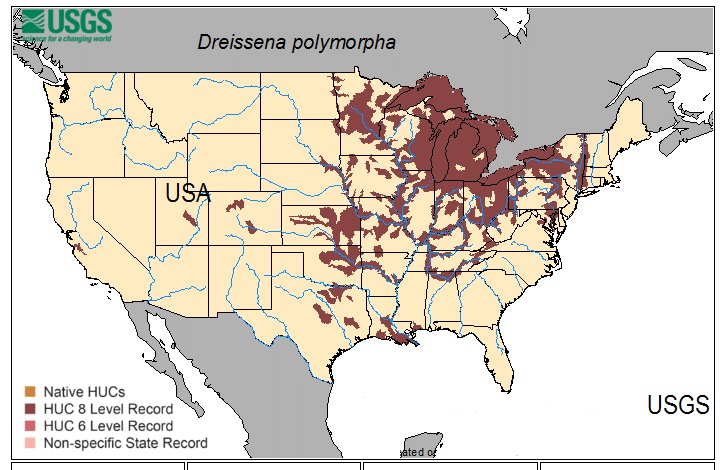

U.S. Geological Survey

Where zebra mussels have invaded inland lakes.