Michigan Supreme Court.

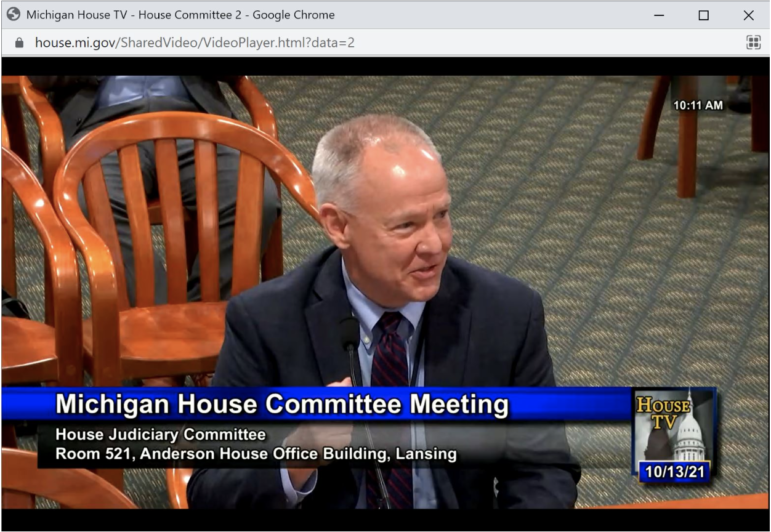

Tom Boyd, who heads the State Court Administrative Office, testifying about court funding at a House Judiciary Committee hearingBy JACK TIMOTHY HARRISON

Capital News Service

LANSING – Local criminal court funding remains uncertain as a deadline next year approaches that could eliminate a major source of money for local trial courts.

Meanwhile, the Michigan Supreme Court is considering whether judges can constitutionally impose costs on convicted criminal defendants. Those costs provide a significant chunk of trial court budgets, up to $291 million annually as of 2019.

The court heard arguments in the Alpena County case of Travis Johnson, who is challenging $1,200 in court costs assessed after he pleaded guilty and no contest to a series of charges. He was sentenced to spend between 13 months and five years in prison on the most serious charge, aggravated domestic assault.

County officials say they worry that if the court rules in Johnson’s favor, the May 2024 sunset for the law allowing such court costs would become irrelevant. That’s because collection of court costs would stop immediately, officials fear.

According to Samantha Gibson, a governmental affairs associate for the Michigan Association of Counties, those costs account for over a quarter of trial court funding.

If the law authorizing judges to impose costs expires as scheduled, and if the Legislature doesn’t fill the budget hole, “this is a massive problem for counties because the problem falls on us to backfill that (money), and we just do not have the funding to do so,” Gibson said.

Deena Bosworth, the director of governmental affairs for the association, said that counties receive less than half of the money to run the court system from the state, calling that financial obligation an “unfunded mandate” imposed on local governments.

“We struggle with the funding for it and have regular battles with the judicial branch and how much we spend for each court. It remains a huge, huge issue,” Bosworth said.

In 2014, the state Supreme Court ruled that courts lack the authority to assess costs in criminal cases since that power was not written in state laws, according to State Court Administrator Tom Boyd.

“So the Legislature’s response was to create court costs,” Boyd said. “But, at the request of the Michigan District Judges Association, they sunseted that, so that we could test to see if it’s a good idea.”

Court costs differ from fines, a form of punishment levied by a judge, and also differ from fees, such as filing fees, according to Boyd.

Boyd said the influence of money in the justice system is a problem, and a top concern about the current arrangement is that judges may feel pressured to assess costs on defendants to financially support court operations.

In 2019, the state Trial Court Funding Commission released its recommendations, including creating a stable court funding system whose money comes from the state.

“If we take that money, whatever money comes in, and only return the money to the court that it needs to operate, no revenue and excessive costs, the theory here is that the pressure on judges to generate revenue will go away,” Boyd said. “They won’t see the fruits of their labor.”

Gibson, of the Michigan Association of Counties, is focused on that recommendation as well because it would “distribute dollars to trial courts based on their operational requirements, but also ensure that local trial courts have the discretion to make their own decisions.”

Appeals Judge Michelle Rick, the president of the Michigan Judges Association, has tracked the issue of court funding.

A financial analysis should be done to determine a defendant’s ability to pay, but mandatory fines and costs must be enforced under the law, Rick said.

Rick, a former circuit judge in Gratiot County, said, “My perspective was, look, if you’re going to make me assess these fines and costs, I at least want to have the ability to review the person’s standing before me and see if they realistically can ever pay them.”

She said she agrees with the Trial Court Funding Commission’s recommendation that judges not make such decisions, and said it is also important to understand that inmates released from prison may struggle or be unaware they have to pay court costs.

If the costs are not paid and if the hearing is missed, a bench warrant could be issued and that person could return to prison, Rick said.

“It shouldn’t matter where a person is arrested for a crime, the law shouldn’t change depending upon where you are within the state,” Rick said. “It’s not so much that the law changes, but recognizing that some counties have different financial pressures than others.”

Boyd said problems in the current trial court funding system will not be fixed in the next 14 months, but he is focused on implementing the commission’s recommendations.

However, a solution could be to extend the sunset date for several more years to allow the Legislature time to solve the issue, he said.

It would be an emergency if the Supreme Court were to find these costs unconstitutional, according to Boyd, since courts would immediately stop collecting costs and each county would have a hole in its budget.

“Even if the statute is constitutional, it is bad public policy, and the question then becomes are we going to have years to fix bad public policy, or are we going to have days to fix an unconstitutional law,” Boyd said.

As for Rick, she said it’s important people have confidence in the courts when they stand before judges, and that judges want to focus on judging.

Judges don’t want to be bill collectors, she said.