Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Fentanyl testing strips are used “off label” to detect dangerous fentanyl in street drugs.By JUDY PUTNAM

Capital News Service

LANSING – New dollars distributed to groups fighting substance abuse can be used to purchase strips that test whether drug dealers cut heroin or other street drugs with often-deadly fentanyl.

The simple paper strips are illegal in some 20 states.

But fentanyl test strips, along with sterile needles and opioid overdose reversal medication called naloxone, are among a wide range of “harm reduction” tactics the Department of Health and Human Services supports. The department recently announced it was distributing the first funds from national lawsuits settled in 2021 against prescription opioid manufacturer Johnson & Johnson and three distributors.

“We are actually saving lives with these supplies,” said Lauren Hodson, a harm reduction analyst for the department who, until recently, worked in prevention services with the Detroit Recovery Project. “We get that direct feedback from people using the substances.”

Fentanyl is a cheap, synthetic opioid often found in street drugs including cocaine, methamphetamine and fake prescription pills. It’s also manufactured legally as a painkiller.

Its potency has driven a dramatic rise in overdose deaths across the nation and in Michigan.

According to Health and Human Services, the state had 3,096 overdose deaths in 2021, up from 2,738 in 2020.

Deaths have grown tenfold since 2000, and each year outpace deaths from car crashes, the department notes.

Fentanyl is 50 times more powerful than heroin and 100 times more than morphine, according to the Centers on Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC reports it as a major contributor to both fatal and nonfatal overdoses.

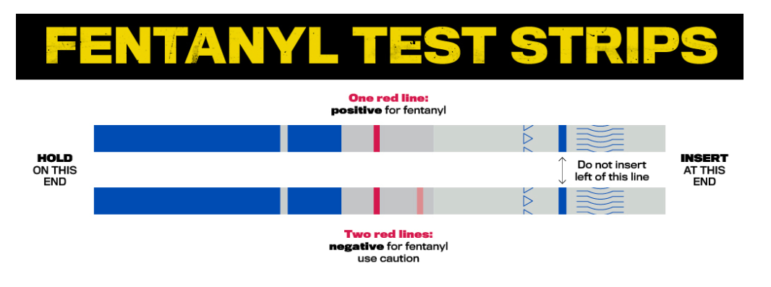

Fentanyl testing strips initially were used to test urine for illicit drugs. They cost about $1 per strip.

For several years, they’ve been used “off label” to test street drugs, using a tiny amount of the drug mixed with water before dipping in the strip.

A June 2022 report from Legislative Analysis Public Policy Association, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit that drafts model state laws on substance use, found that using fentanyl strips is legal in 25 states, including Michigan, but illegal under laws in other states prohibiting drug paraphernalia.

Since that 2022 report was released, more states – Ohio, Georgia, Tennessee, Louisiana and Pennsylvania, according to news reports – legalized the strips and still more are debating legalization.

Some opponents argue that the testing strips promote drug use, but many states are reversing course as fentanyl-related overdoses rise.

Michigan never outlawed the testing strips though it has a law dating back to 1978 that criminalizes drug paraphernalia. The law applies only to those selling drugs, according to the association’s study.

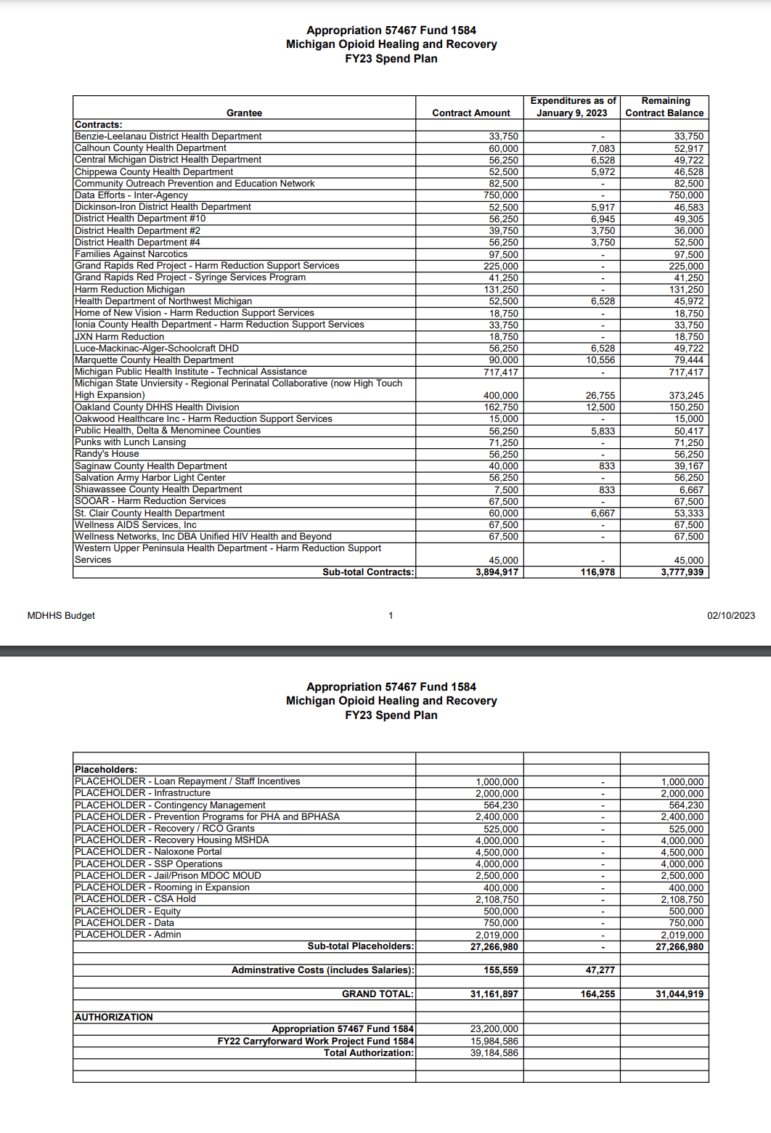

The opioid settlement will total nearly $800 million to the state and local governments over 18 years as part of a $26 billion national settlement. As part of the first $39 million received by the state, Health and Human Services said it’s distributing $3.9 million to 34 nonprofits and health departments operating “syringe service programs” offering clean needles and other supplies to those using street drugs.

Those groups have grown from five in 2018 to 34 today, according to Lynn Sutfin, a department public information officer. Many have distributed fentanyl testing strips using private donations because they weren’t allowed to buy syringes, testing strips and other supplies with federal drug prevention dollars until the Biden administration approved it in 2021.

Sutfin said the state’s approach to addiction is supportive and promotes “change at your own pace.”

“Get some of these individuals in the door, and maybe they are ready at some point to take that next step,” she said.

Steve Alsum, the executive director of the Red Project in Grand Rapids, said his syringe services group serves six counties: Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, Newaygo, Lake and Allegan. It offers naloxone in three more counties: Mason, Oceana and Montcalm.

From October to December 2022, the group served 3,300 individuals and distributed 4,800 fentanyl testing strips.

“First and foremost, fentanyl testing strips are a tool that enables people to have a greater degree of knowledge of what they’re putting in their body. People can then use that to make decisions to reduce the risk,” he said.

He supports the use of fentanyl testing strips but said they aren’t perfect.

For example, they can’t identify all forms of fentanyl. Because fentanyl has grown so pervasive in heroin, most heroin samples test positive, he said.

The strips have been more useful in recent months to identify fentanyl contamination in cocaine and methamphetamine, he said.

Kelly Rumpf, a health educator at the Dickinson-Iron District Health Department in the Upper Peninsula, said fentanyl strips, along with sterile needles, naloxone, sharps containers and alcohol wipes, are at the health department office in Kingsford.

The service, which helps 150 to 200 people a year, depends on word of mouth because local officials have shied away from promoting it, fearing public backlash, Rumpf said.

“People look at it like we’re enabling,” she said.

But it’s needed because the area has a high hepatitis C rate that can be spread by sharing needles, she said.

“It’s building momentum,” Rumpf said of the syringe services program.

Julia Miller, the executive director of Punks with Lunch Lansing, said she views testing strips as one way to remind substance users to be careful and think about recovery. Her group feeds people who lack housing, provides warm clothing and staffs an office at a former church called the Fledge where syringe services are offered.

Fentanyl testing strips are a routine part of the outreach to about 35 people a week.

“It’s making more people aware of what they are using,” she said.

Miller added that getting a test that is positive for fentanyl doesn’t mean users throw those drugs out.

“Most of them tell me they make sure they use a little less of it or make sure they have someone with them,” who could administer overdose aid, she said.

Community Health Awareness Group in Detroit enrolls about 2,500 people in its syringe service program, said Barbara Locke, its director of prevention programs.

Fentanyl testing has been used for a few years, she said, and her group has worked on educating drug users on how to use the tests.

“Knowledge is power,” Locke said. “Fentanyl is so dangerous. We don’t want them to overdose. They don’t want to overdose. Nobody wants that.”