By ANASTASIA PIRRAMI

Capital News Service

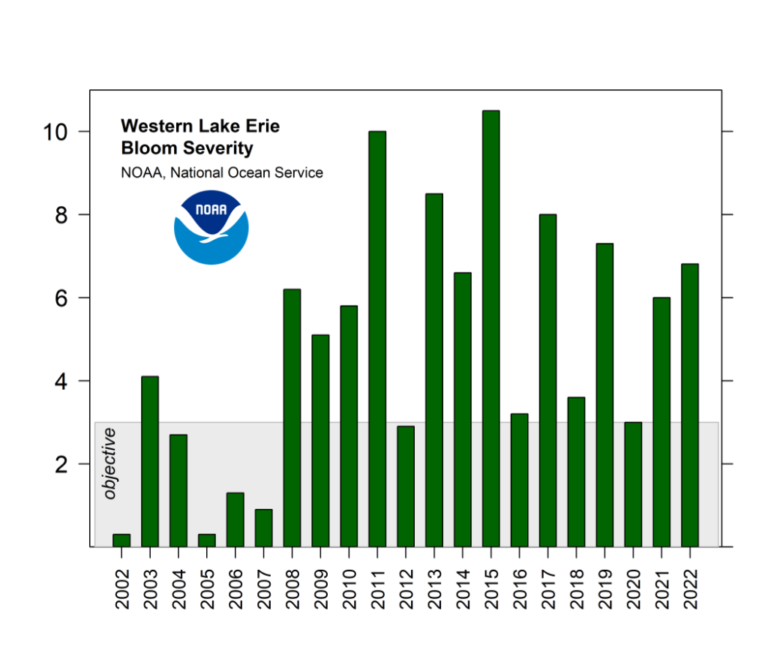

LANSING – Harmful algal blooms were much larger in Lake Erie than experts predicted for 2022.

A year-end report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said that the algae bloom was more severe than expected because of an increase in biomass that caused more algae.

There are two reasons, said NOAA oceanographer Richard Stumpf.

One is a longer-than-normal peak of bloom.

“What we saw this year was a plateau rather than a peak,” Stumpf said. “A typical year goes up, hits a peak level and comes down.

“Now, that peak might be really large for a severe bloom like 2011 or 2015, or it might be small, but it generally goes up to a peak. This year tended to hit that maximum state at a plateau for a month,” he said.

Stumpf describes the plateau as “newish.”

The algae bloom was more extreme last year, but it seems to be trending that way because the blooms seem to be starting earlier than they did 15 years ago, he said.

Another reason is phosphorus, the key nutrient affecting the blooms in Lake Erie, Stumpf said.

NOAA predicts the amount of phosphorus entering the lake from the Maumee River and other sources to calculate the expected bloom. In 2022, there was more than anticipated.

“So, there’s either phosphorus that was used more efficiently this year, or there’s some additional source of phosphorus that may be in the lake or such that we’ve not accounted for,” Stumpf said. “The combination of both are a part of the factor for the underestimate of the bloom.”

One idea that could further explain the bigger algae bloom is rising water temperatures, said Laura Johnson, the director of National Center for Water Quality Research at Heidelberg University in Ohio.

Johnson said that doesn’t mean that temperatures were very hot last fall, but rather not as cool as typically expected for algae blooms to still be around.

In a typical year, microcystis algae blooms in spring and summer. By September or October, the weather starts to change in a way that not amenable for the blooms survival, Johnson said. The water tends to have more waves and turnover during the fall, compared to calmer water in the summer, she said.

Microcystis is a type of cyanobacteria that grows naturally in freshwater. When algae blooms form and cyanobacteria degrade, many release algal toxins that can be harmful, according to the Environmental Protection Administration/.

Stumpf said cool fall weather will stop the microcystis from growing and dispersing through the lake until they are gone.

In 2022, the bloom switched from microcystis to a different type of blue-green algae called dolichospermum that tolerates cooler water better than microcysts. It does occur in Lake Erie but generally does not bloom.

The two major nutrients that dolichospermum need are phosphorus and nitrogen.

“One of the thoughts is that the bloom was able to continue on because it was able to pull nutrients from a different source,” Johnson said.

There’s still a lot to be learned about the blooms, such as whether air and water have any effect on the bloom or whether it may be something else, she said.

Stumpf said, “We can say that it’s reasonable for it [dolichospermum] to be there, but we don’t have a good explanation as to why it appeared this year and it hasn’t appeared in other years.”

The prediction model was inaccurate possibly due to the duration of time that the biomass estimate was taken, Stumpf said. That can be corrected by more accurately estimating when ta bloom starts by relying more on when water temperatures increase, he said.

There’s a temperature dependency that could be accounted for. That means that if waters are warmer, then the bloom will start sooner.

The second part of correcting the prediction model appears to be determining why more phosphorus was used last year than in the past, he said. That’s still a research question for NOAA because there could be a multitude of ecological factors involved.

Potential explanations include phosphorus coming from sediments or competing species in the lake.

The only other year that was a problem for the prediction model was in 2013, Stumpf said. If there is a similarity between 2022 and 2013, that gives NOAA a reasonable chance of explaining why the bloom was much bigger last year.

“It becomes very difficult if you only have one year with a problem,” Stumpf said. “I’m hoping that between looking at these two years out of the last 20 years, that we can come up with an explanation and then an adjustment for the model to correct us.”Anastasia Pirrami reports for Great Lakes Echo.

NOAA

Bloom severity index for 2002–22. The severity index is based on the amount of biomass over the peak 30-days. The 2022 bloom had a severity of 6.8.