Yuri Tomkiw was in his apartment on Feb. 24. CNN was on the television.

Tomkiw, a neuroscience student at Michigan State University, was watching live coverage of Russia’s early-morning invasion of Ukraine.

“I was just pacing back and forth across my apartment, just watching,” he said.

Tomkiw, 21, was born in the United States, but his grandparents are from west Ukraine.

He founded the Ukrainian Students Organization at MSU in 2019. It now boasts 48 members, most of whom are part of the Ukrainian diaspora in the U.S. But student engagement outside the organization has been a challenge.

Related story: MSU joins other U.S. universities in discussing Russia’s war on Ukraine

The first few weeks of the conflict gripped the world, but as it enters its tenth month, the war is less visible on Americans’ radar. A September poll by Pew Research Center found that 11% fewer American adults are following news about the conflict “extremely or very closely” than in March.

“Students don’t really care,” Tomkiw said. “It’s a war far away, and it doesn’t involve (them).”

But for people with direct ties to Ukraine — and the Michigan-based groups working to help them — it is always close.

Several members of student organization still have family in Ukraine, some of whom are fighting on the front lines. Tomkiw said it’s a source of pride. But that doesn’t diminish the ugly parts of the conflict.

“The best thing the MSU community can do is talk about it,” Tomkiw said. “This isn’t like a normal war.”

He urged his peers to stay informed about the conflict, even when it becomes difficult, citing allegations of war crimes by the Russian military.

Yuliya Mironova, a fifth-grade English teacher, was corralling 10-year-olds in Ypsilanti when she first learned of the invasion.

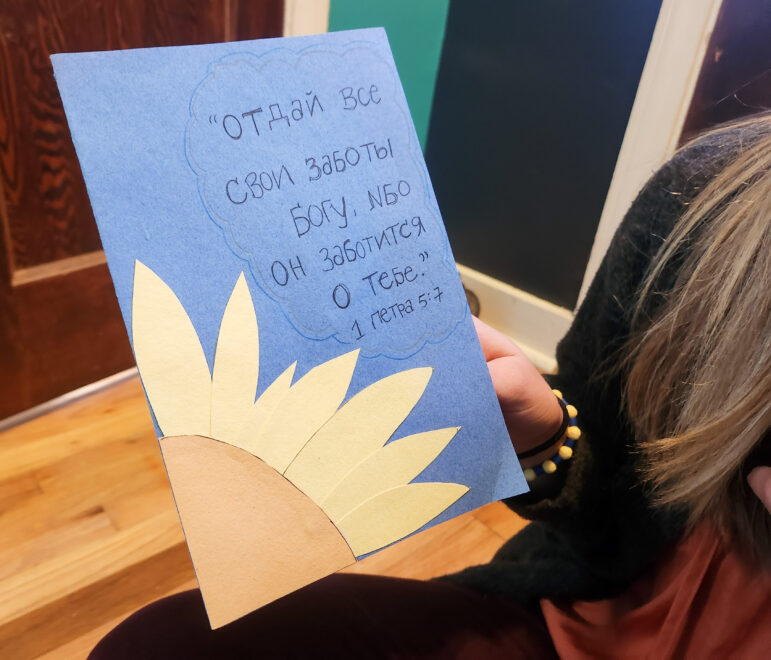

Mironova, 27, was born in the former Soviet state of Uzbekistan to Russian parents. Her family moved to Grand Rapids when she was 2, but she grew up speaking Russian. Mironova visited Warsaw, Poland, in mid-May to volunteer at the Ptak Humanitarian Aid Center.

“I was hoping my Russian could be useful,” Mironova said.

Although Ukrainian is the official language of the country, 30% of Ukrainians speak Russian as their first language.

For a week, her small team organized activities for children living at the shelter. Ptak is the largest refugee center in Europe, hosting 20,000 refugees. Mironova described a sea of cots and sleeping bags laid out in conference halls.

“Seeing everyone so displaced in their lives, just on full display was hard,” she said. “Just seeing these like, full-blown adults, you know, just kind of like crumpled on beds and just kind of broken.”

Mironova said the conflict isn’t as far away as it may seem. A few Ukrainian families have started attending the school where she works — Mironova has been translating for them — and more are on their way.

“It’s like literally trickled into Ypsilanti already,” she said.

Most Ukrainians come to the U.S. under the United for Ukraine program, introduced by the Biden administration in April. Individuals enter the country as humanitarian parolees (not refugees) after connecting with a sponsor already in the U.S.

“There’s a couple kinks in the hose,” said Melissa Goodson, chief development officer at Jewish Family Services of Washtenaw County. “We are the bucket that everybody lands in when the water comes gushing out.”

Sponsors are supposed to help newcomers – financially and logistically – reach independence. Mira Sussman, resource development manager for Jewish Family Services, said it’s not that simple.

“What’s really happening is sponsors don’t know how to do that,” she said. “We have to jump in.”

The organization helps Ukrainian parolees and other refugees with housing, transportation and other critical needs. Other services include health training, employment services and English-as-a-second-language programming.

Sussman said the group has worked with 60 Ukrainians so far in 2022 who have already applied to resettle in the area. She expects “many more” in 2023.

“Sixty is just the start,” Sussman said.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 87% of Ukrainian refugees are women and children. Men of military age are not allowed to leave the country, so family groups often consist of older adults, women and their children.

Goodson estimated it costs $10,000 to get a family “back on their feet.” But the federal government provides resettlement organizations with “very, very, very little funding” to support Ukrainian parolees. To make up the difference, support organizations need members of the community to donate time, household items and money.

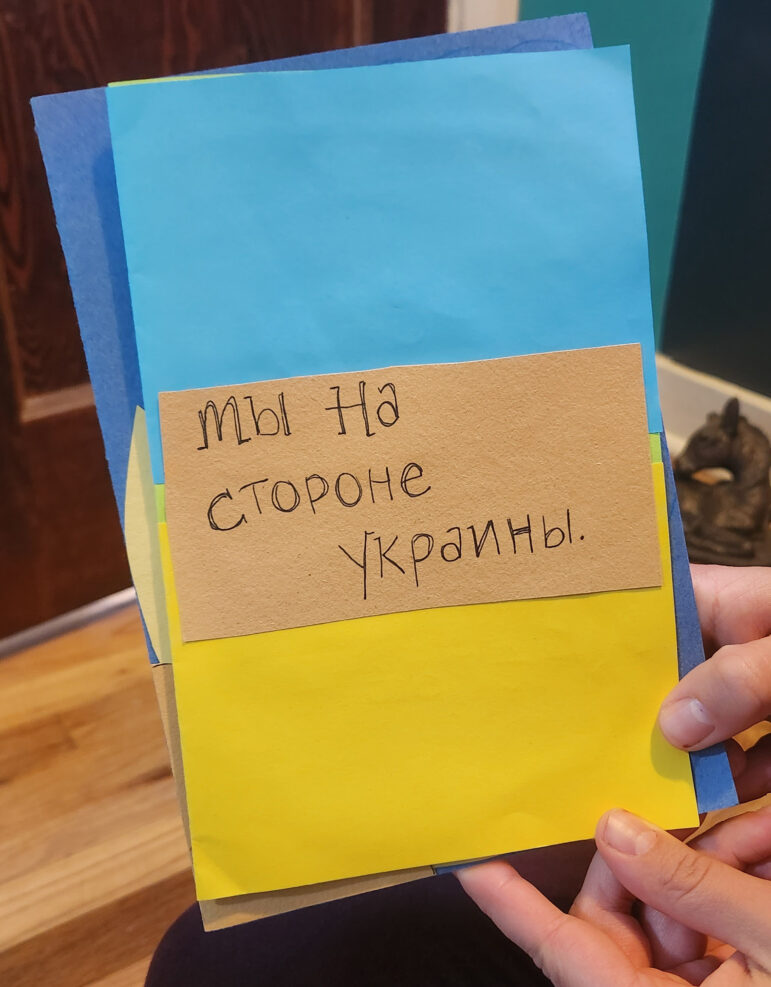

There are other ways to contribute, too. She emphasized “making sure people feel safe.”

“What they need are welcome faces, smiles, help,” Sussman said. “Stop by and say, ‘Do you need something?’”

Ukraine Fast Facts