Two-hundred seventy-eight Afghan refugees have arrived in Lansing since August 2021. St. Vincent Catholic Charities has received all of them.

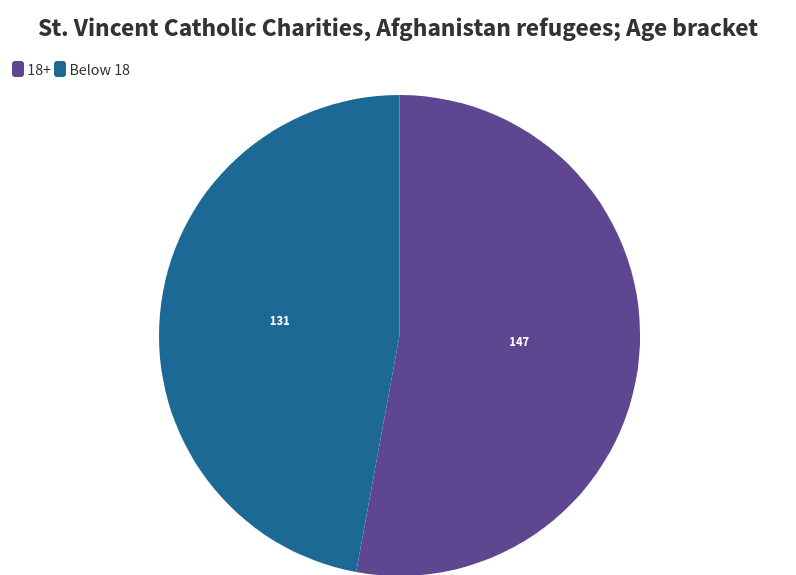

Judi Harris, director of refugee services at St. Vincent Catholic Charities, said the organization sets up housing for refugees, provides job assistance, offers English classes and gets people signed up for benefits, such as Medicaid. She said that of the 278 Afghan refugees, many are young children. About half are under 18. Four babies were born here, and 13 more babies are on the way.

Olivia Schornak

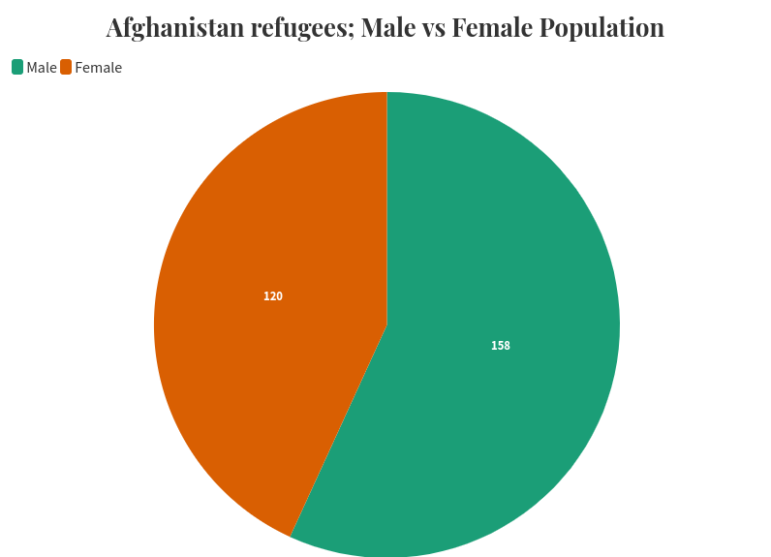

St. Vincent Catholic Charities welcome many refugees. Based on gender, they have received 158 men and 120 women since 2021.

Even though some families were able to stay together, many more were separated.

“We have stories of people who, at the airport, the door closed with their family on the other side, and they ended up getting on the plane alone,” said Harris. “Plus, what’s happening now in Afghanistan is very concerning for everybody because there’s still a brutal regime there. There’s no economy anymore. They’re predicting mass starvations. There’s a drought. A poor harvest. So everybody here is very very concerned about their families over there.”

Afghans are being driven from their homes after the Tablian took over the country in August 2021. The Taliban takeover displaced about 700,000 Afghan people according to the UN Refugee Agency. The United States has welcomed over 70,000 of those refugees. Michigan is expecting about 1,300. Three hundred will be resettled in Lansing. This is one of the largest refugee resettlement efforts Michigan has seen since 2010.

As well as being separated from family, the Afghan refugees are arriving in the United States with trauma, said Harris.

“Most of them are under a lot of stress, partially because they’re fresh from a conflict. Usually, when we’re resettling folks, they’ve been in a refugee camp for a while or some kind of holding situation overseas. These Afghans were witnessing atrocities as they were getting on the plane.”

Olivia Schornak

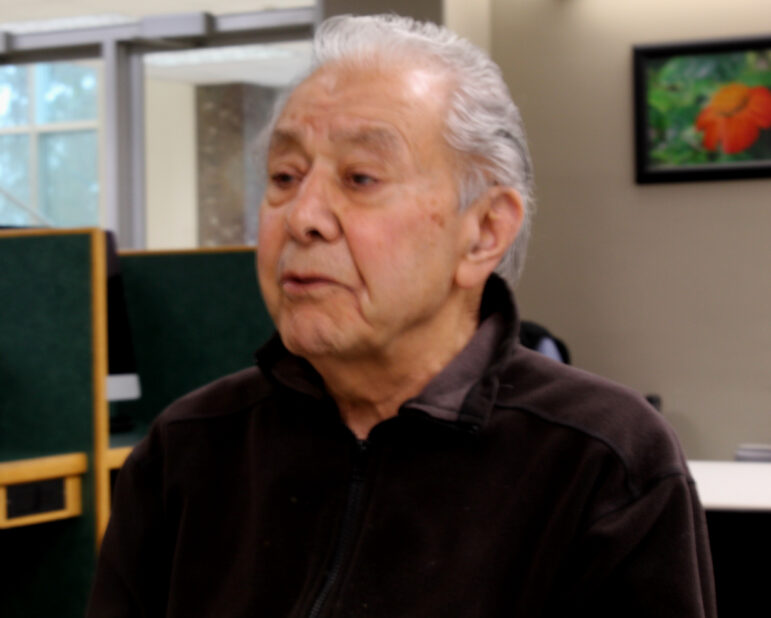

Dr. M. Jamil Hanifi, 86, speaks about his expertise in immigration policy, his many years building an education, and life as an Afghan immigrant.After getting away from the conflict, Afghan refugees are put in a new environment with an unknown culture and language. Adjustment can be tough.

Dr. M. Jamil Hanifi was born in Logar Province, Afghanistan, in 1935 and raised near the capital Kabul. After high school, Hanifi received a scholarship sponsored by the Afghanistan government to attend university abroad. He decided to come to the United States and study police administration at Michigan State University in 1956.

Hanifi is not a refugee. He is an immigrant, but, like refugees, he had to adjust to a new culture.

He said he drank his first Coke and went to his first club during his layover in Tehran, Iran. He was 20. At university, Hanifi said his friends introduced him to new American experiences. He celebrated his birthday for the first time the day he turned 21.

“I had never celebrated a birthday or anything like that in the culture I was raised in,” said Hanifi, who grew up in an urban Pashtun tribal society. “It was June 27, my birthday. That day I hear a knock on my door. It was my roommate and several other guys singing ‘Happy Birthday.’ They said, ‘Come with us. We will celebrate your birthday.’ So, we walked to a bar, and I had my first beer.”

Hanifi said learning English was another cultural adjustment he struggled with. At MSU, Hanifi took an English improvement class because his English was “zilch.”

He said, “My English teacher sometimes got mad at me because I would ask him, ‘Why do you call a woman Miss and yourself Mr.?’ I had a lot of questions like that.”

Harris said the biggest challenge for refugees coming to the United States is not knowing the language. It prohibits them from being able to communicate their needs and understand what is going on around them, Harris said.

St. Vincent Catholic Charities and the Refugee Development Center provide English classes for incoming adult refugees. Harris said once they learn English, they can get a job and become less reliant on assistance.

For younger refugees, language teachers help students learn English in school. Sara Daniels is an ESL teacher at Caledonia Public Schools in West Michigan. She teaches two Afghan refugees in 9th grade.

Daniels said her primary goal is to help her students learn English, but her support “goes well beyond the classroom.” She works as an informal counselor and as their advocate. She said her students often come to her first when they have a problem.

In April, Daniels said she had to advocate for her Afghan students during Ramadan because some teachers were unaware of the Muslim holy month’s traditions.

“I had our Afghan students’ foster mom reach out to me. She wanted me to reach out to the gym teachers to let them know that doing gym class during Ramadan is actually really hard for our Afghan students because they can’t eat or drink anything, even water, during the day.”

ESL teachers ease Afghan refugee students’ adjustment to their new community. Daniels said even though the job can be emotionally taxing, it’s rewarding to be able to help her students.

“If I can help make their transition to life here even just a little bit easier, it means the world to me.”

— Sara Daniels

“I remember particularly when these two boys started to feel comfortable enough to be their goofy selves, and we could start to see who they really are. That to me was massive,” she said. “If I can help make their transition to life here even just a little bit easier, it means the world to me.”

Beyond the classroom, Harris said the Lansing community has “poured out support” for the Afghan refugees. They’ve received cash donations, furniture and household goods, and many people have volunteered as mentors and friends. All the support has helped the Afghan refugees integrate into the community.

“We hope and we know that they are going to be really successful,” said Harris. “We look at the kids and think ‘Gosh, you’re going to live here, and you’re going to be able to eat a meal every night and sleep in a safe, warm bed. You’re going to be OK, and you’re going to go to school. And you’re going to have a good life.’ And I don’t think that’s the case for all of them if they had stayed in Afghanistan.”