By SYDNEY BOWLER

Capital News Service

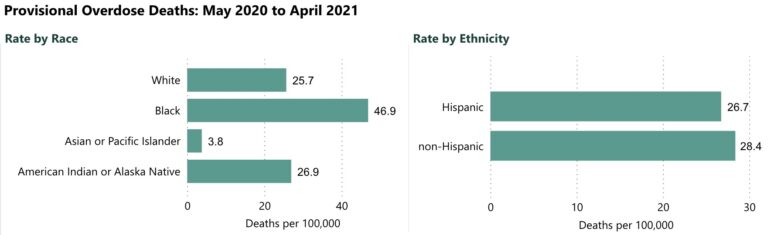

LANSING – Opioid overdose deaths have increased dramatically among African American and Hispanic populations in the state, according to new data from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

In Michigan, the opioid overdose death rate among Black residents rose by 28.8% between 2019 and 2020 and by 48.6% among Hispanic populations.

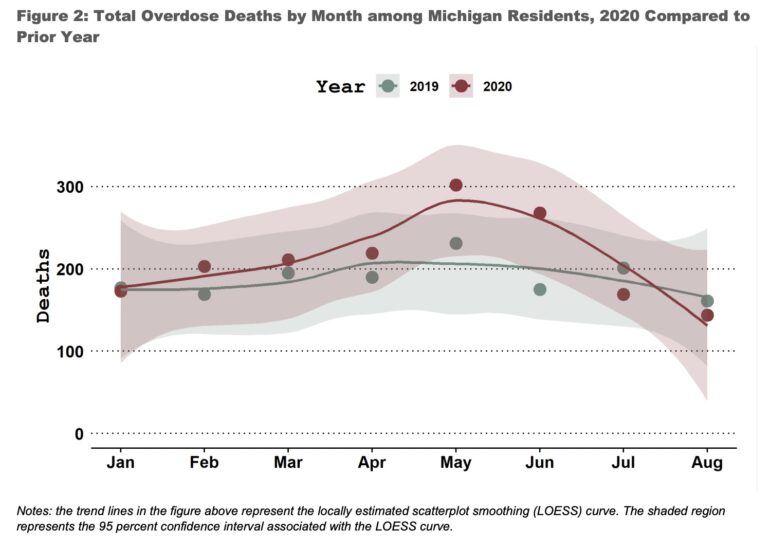

Among all races and ethnicities, there was a 12.7% increase in the number of overdose deaths from January through August 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.

Nationally, there was a large increase in drug overdose deaths from April 2020 to April 2021, mostly from synthetic opioids, according to preliminary data from the the National Center for Health Statistics.

“The growing disparities in overdose data that we are seeing in (Black, Indigenous and people of color) communities have made it clear we need to refocus on our strategy to better improve services for these communities,” said Chelsea Wuth, an associate public information officer for Health and Human Services.

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

Total overdose deaths by month of Michigan residents.According to the state, the five counties with the most overdose deaths from May 2020 to April 2021 are: Wayne (826), Macomb (332), Oakland (237), Genesee (183) and Ingham (116).

To combat racial disparities in overdose deaths, the Michigan Opioids Task Force put together a Racial Equity Workgroup to develop initiatives to expand services for affected communities and raise public awareness to reduce the stigma of substance abuse disorder, according to Wuth.

The work group will also develop recommendations to reduce racial disparities by “harmful and unjust” government policies and practices that create inequities in health care based on race, ethnicity, gender identity, class, sexuality, geography and disability, she said.

“Inequities in health care exist among African Americans. Despite the rise in African American overdose rates, opioid use disorder is often perceived as mostly an issue among white populations,” Wuth said.

The workgroup will collaborate with the Opioids Task Force on proposals to reduce racial disparities by creating new systems, policies and practices.

According to Mark Greenwald, the director of the substance abuse research division at Wayne State University, many factors explain the increase in opioid use and overdoses.

“Some treatment facilities cut back in-patient (capacity) when COVID initially hit, along with structural changes to out-treatment programs that made it more difficult for patients to receive their (treatment) doses,” Greenwald said.

Only around 10% of those with opioid use disorder are in treatment, Greenwald said.

“We need to get more people into treatment because it’s lifesaving,” he said. “The medications we have that are FDA-approved reduce the risks of overdose and death, and that helps stabilize the individual so they can begin recovery, which is a longer-term process.”

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

Provisional overdose deaths: May 2020 to April 2021.COVID-19 has also put broader stresses on the community and has temporarily altered health care for people with opioid and other substance use disorders, he said.

Greenwald said the pandemic has exacerbated mental health problems.

“People who are susceptible to drug use, (their) emotional or physical problems may lead people to use opioids more,” he said.

One potentially positive outcome of the pandemic was a loosening of outpatient methadone regulations. That removed restrictions of taking home doses of methadone, providing more flexibility and care for patients, he said.

Meanwhile, Wayne State’s Opioid Workforce Expansion Program aims to prepare workers in the field, according to Anwar Najor-Durack, the assistant dean for student affairs in the university’s School of Social Work.

That training emphasizes working with people at risk of, or who are already developing, an opioid or substance abuse disorder in high-need areas, like Detroit.

“Our hope is that these folks will have an interest and be dedicated and find positions in our community in Southeast Michigan, and provide these services for people who really need them,” Najor-Durack said.