By BARBARA BELLINGER

Capital News Service

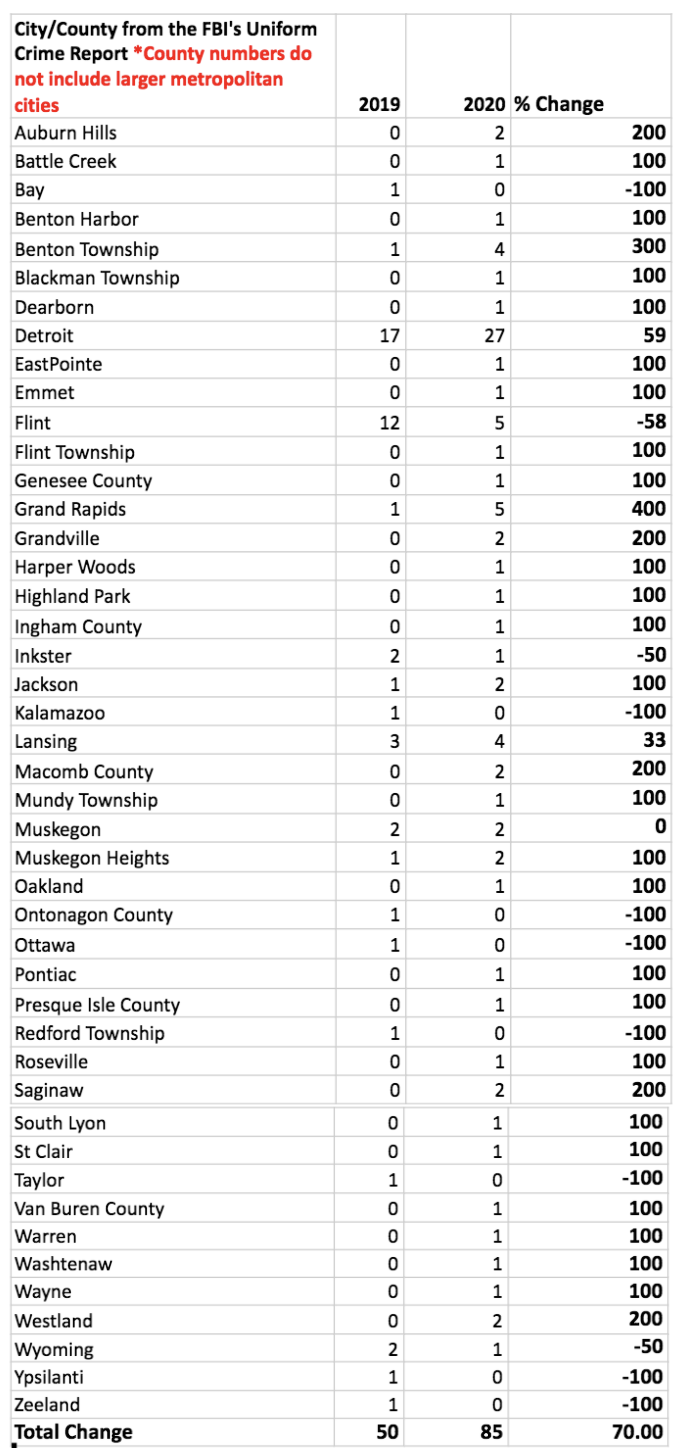

LANSING — The number of Michigan teenagers killed by homicide jumped by 70% from 50 in 2019 to 85 in 2020.

That’s more than double the 31% increase of all homicides for the same period, according to the FBI’s recent Uniform Crime Report.

Teen homicides in cities such as Grand Rapids, Lansing and Detroit rose. The greatest increase in number of homicides was in Detroit, up 59% from 17 in 2019 to 27 in 2020. Most of the deaths were a product of gun violence.

Flint was one of the rare cities that experienced a drop in teen homicides. The city’s teen homicides decreased by 58%, from 12 in 2019 to 5 in 2020.

Other contributors to the 70% increase lie scattered across the state in smaller municipalities that went from zero juvenile homicides to one or more.

There has been a noticeable increase in youth aggression and violence in schools across the nation, said Marc Zimmerman, the director of the Youth Violence Prevention Center at University of Michigan, one of only five National Centers of Excellence in Youth Violence Prevention funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Trends on social media encouraging theft and violence are among the drivers of the increase, say community advocates in Jackson and Lansing.

They cite TikTok’s “devious licks” trend, which encourages students to steal items from schools, and the “slap a teacher challenge” in which students film themselves hitting a teacher on the back of the head.

TikTok and Snapchat are popular social media platforms for watching videos and making and posting your own.

The platforms are also sed by teenagers to call each other out, said Allen Anderson, a co-partner of Yardables, a boxing club in Jackson that brings young people together to work out their differences in the “yard” rather than on the streets.

Anderson used to be a security guard, substitute teacher and football coach at Parkside Middle School in Jackson. Some of the kids he got to know are now in high school and on Snapchat, he said.

“There’s a guy on my Snapchat. He’s antagonizing all these different gangs. He’s calling them out. He’s posting his location. He’s trying to get more people to shoot at him.”

“Kids continuously troll each other, you know, embarrass each other, bully each other,” said Michael Lynn Jr., co-founder of the nonprofit The Village Lansing, which focuses on empowering Lansing’s youth.

Some of that is done through drill music, which is defined by its violent lyrics.

“They’re making these, you know, songs where they’re talking about actually going out and doing these violent things,” Lynn said.

It’s not just about social media and types of music, although those contribute to the problem.

The issue of increasing teen violence that leads to homicide has multiple layers that encompass screen time, the pandemic, environmental triggers and adult influences, said Zimmerman, who holds a doctorate in psychology.

“One of the things I often say is that the youth violence problem isn’t a youth problem. It’s an adult problem, we’re the ones who created the world they live in,” he said.

Flint and Genesee County have been a focus of Zimmerman and his colleagues’ efforts in youth violence prevention. They have partnered with Flint and Genesee County organizations and community members since the mid-1990s.

In 2010, they began collaborating on a multilevel approach that includes youth empowerment, father-son and mentoring relationships and community focused projects.

The approach brings residents, community organizations and law enforcement together and couples it with evidence-based research to gain an understanding of what is working and what isn’t.

Recently, Anderson spoke at an assembly at Parkside Middle School. When he asked the kids what wasn’t working and what they thought the community needed, hands went up across the room.

“A lot of them said after-school programs and additional gyms being open,” he said.

“These kids, they feel like if there’s nothing for them to do, like, they’re going to find something to get into, and nine times out of ten it’s not going to be positive.”

“One of the things that has changed over the past decade is funding to after-school programs, which provide activity for young people, more constructive activity, be it educationally based or recreationally based,” said Flint police spokesperson Detective Sgt. Tyrone Booth.

This reduction in funding has led to teenagers being put out into their community when school gets out and they have time to get involved in things that aren’t constructive, Booth said.

FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports

Spreadsheet of the teenage homicides in Michigan counties and major metropolitan areas in 2019 and 2020 recently reported in the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports.“And, typically, that’s crime.”

In Lansing, teen homicides by gun violence in 2021 have already surpassed last year’s numbers by 133%, from three deaths to seven, as reported by the Lansing State Journal.

Lansing officials recognize that the lack of after-school activities for young people are a problem and are working on making changes.

“Once COVID allowed, we reopened community centers and reactivated many programs for our youth,” Mayor Andy Schor wrote in an email. “We’ve allocated new funding to youth programming, as well as street outreach to reform those who may already be going down the wrong path.”

Whether it’s the wrong path or a perfect storm of external influences, violence and aggression can be a precursor to homicide.

“Rarely is it a person just picking up a gun and shooting somebody,” Zimmerman said. “They get aggressive first. Then that aggression leads to retaliation, and somebody feels like they need to carry a gun to protect themselves.

“And the next thing you know, homicide’s happening.”