By CHIOMA LEWIS

Capital News Service

LANSING — Researchers are asking for volunteers to transcribe paper records on fish observations that date back more than a century.

The historical data from lake surveys will help scientists understand how climate change and other factors have affected fish in Michigan lakes. The records report characteristics of fish communities, food sources, plant life, water conditions, human development and lake mapping.

Some of the oldest records are from the 1880s.

The effort is part of the Collections, Heterogeneous data and Next Generation Ecological Studies, a project at the University of Michigan, and is funded with a $90,000 grant from U-M’s

University of Michigan

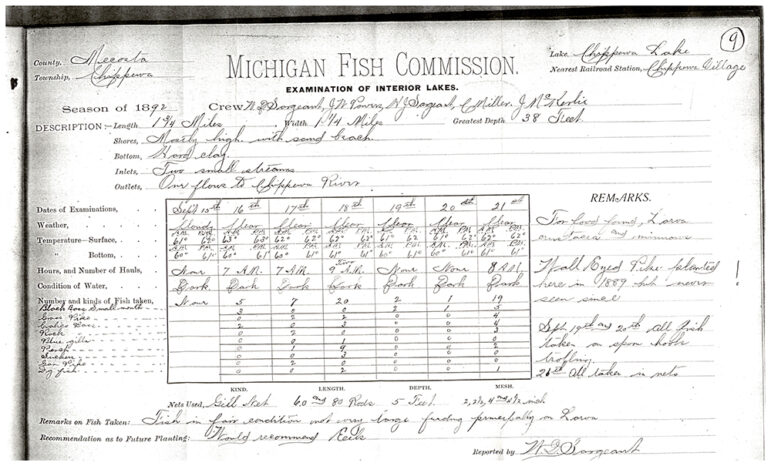

Scanned paper shows examination of Chippewa Lake by the Michigan Fish Commission in 1892.Michigan Institute for Data Science.

Students started scanning data on the cards last year before the process stopped because of the pandemic. They worked at U-M’s Institute for Fisheries where the lake surveys are archived.

The scanning became difficult due to COVID-19 shutdowns. Also, attempts to digitize the cards were hampered by computer software that couldn’t recognize the text well, said Karen Alofs, an assistant professor of ecosystem science and management.

That’s when the research team looked to the Zooniverse platform for help. Zooniverse is an open-source site where anyone can build a project and people volunteer to assist professional researchers.

The platform makes it possible to digitize cards with years of lake survey data. The research team uploads images of each card for volunteers to transcribe.

“When an image is transcribed or classified in some way — it’s going to be done multiple times by different people. That’s how they do sort of data quality check,” said Justin Schell, the director of the Shapiro Design Lab at the U-M Library.

Each image of a single or double side of a card must be classified four times before it is completed.

Alofs said multiple volunteers transcribing data helped the project get past errors from other methods of transcribing.

From a research perspective, Schell said, the most important part is the connection, education and engagement with the people who transcribe the cards. That allows researchers to engage with the volunteers and learn from them.

“The volunteers in some ways become the experts too,” Schell said. “After seeing these cards so often, they’re teaching us things — about the cards — that we didn’t know about.”

Zooniverse’s talk option lets researchers and volunteers provide questions or feedback about the project and discuss individual subjects.

Volunteer participation gets people who are interested in the lakes and fish involved in recording the data and seeing how things change, Alofs said.

“A lot of people are really interested in what’s happening with fish — in lakes that they visit quite often, or they live near, or they’ve heard about,” Alofs said.

The most immediate thing researchers are looking at is the impact of human-caused climate change on water temperature, Alofs said. They will also examine different management approaches and other environmental factors that control the location of fish.

Many declines in freshwater species are due to multiple stressors and changes in the environment like water quality, temperature, invasive species and shoreline development, Alofs said.

Researchers plan to pair the data from the lake surveys to fish specimens and field notes from the collections at the university’s Museum of Zoology.

The data will also create models that can project how species’ distributions will change and how the abundance of fish will change.

“What I often find, in thinking about how lakes or fish are changing through time, is that we really rely upon the data that’s been collected in the past,” Alofs said. “And the people that collected this data couldn’t have imagined what we’re doing with it now.”

Because of the remaining large number of subjects to be classified, Schell says finishing the project will take awhile.

“We probably have another 10 to 15, maybe 20,000, images to put up,” Schell said, estimating that the project will take at least six months to complete.

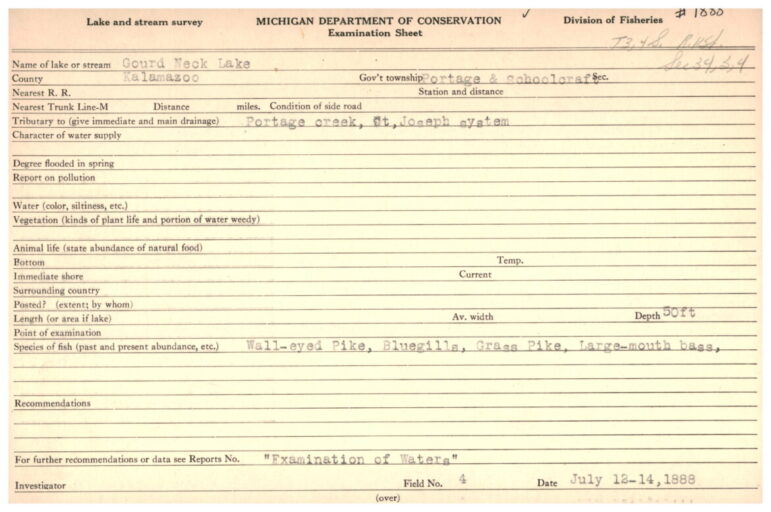

University of Michigan

Scanned card shows lake survey of Gourdneck Lake by the Michigan Department of Conservation in 1888.More than 600 people have volunteered, but the more who are involved, the better, Alofs said.

“This is kind of a unique project. People could sit at home and do this, and capture this data at the same time.”

Chioma Lewis reports for Great Lakes Echo.