By AUDREY PORTER

Capital News Service

LANSING — During 35 years of restoration in the Great Lakes Areas of Concern, there has been gradual progress and a hopeful future ahead, according to a new study.

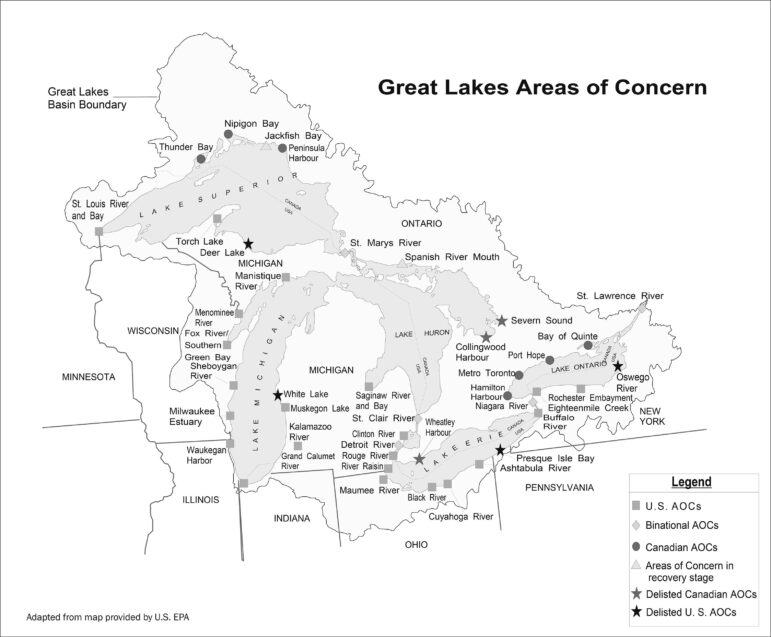

Development of a remedial action plan to restore heavily contaminated sites in 42 Great Lakes Areas of Concern in the U.S. and Canada began in 1985.

Restoration hasn’t been easy, the study said, and it requires focusing on gathering stakeholders, coordinating efforts and ensuring the restoration of a variety of safe uses.

As of 2020, eight Areas of Concern were removed from the list, including the Lower Menominee River on the Michigan-Wisconsin border, White Lake in Muskegon County and Deer Lake in Marquette County. Two others were designated as “in recovery” and 169 environmental impairments were eliminated.

Still listed as Areas of Concern are parts of the Detroit River, Clinton River, River Raisin, Manistique River, Muskegon Lake, Saginaw River and Bay, St. Clair River, Kalamazoo River, St. Marys River, Rouge River and the Upper Peninsula’s Torch Lake.

Between 1985 and 2019, a total $17.55 billion (U.S.) and $6.50 billion (Canadian) was spent to clean and restore the areas. That’s a total of $22.78 billion in U.S. dollars.

“I think it’s a kind of a jaw-dropping number to see $22.78 billion being spent. It’s encouraging when you take that information in the context of the economic benefits that come from investing in cleanup and restoration,” said Peter Alsip, a scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Great

Lakes Research and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory in Ann Arbor.

“My take is that it is encouraging for the rest of the program,” said Alsip, who participated in the study.

John Hartig, an award-winning Great Lakes scientist and co-author of the study, said communities should be involved in restoration efforts.

“We need to inform people about these programs and need to encourage them to get involved, whether it’s citizen science or stewardship programs like river cleanups in the Detroit River or tree planting or invasive species management,” Hartig said.

“There’s so many ways of getting involved in citizen science and stewardship. And the key to that is we’ve got to educate people, and then we have to provide them with opportunities,” said Hartig, the former refuge manager for the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge.

Hartig said a unique thing about the remediation programs is that they call for an ecosystem approach, and an ecosystem approach was a game changer because it led to the creation of organizations like Friends of the Rouge and Friends of the Detroit River.

Co-author Gail Krantzberg, a professor of engineering and public policy at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, said communities have come together over the past 32 years to bring back the ecosystems, to reinvigorate habitat and to clean up the sediment so that the fish and wildlife populations can survive.

The cleanup is not just about the environment, she said.

“It’s really an economic revival of the waterfront, which was a really important finding,” Krantzberg said.

“Prevention is worth a pound of cure,” she added. “Of course, if you can stop something from injuring something else and you don’t have to treat an injury, it’s way, way more cost-effective prevention.”

Raising awareness about how individual actions affect the lakes beyond industrial pollution is crucial.

“So if people understand that when you pour your oil from your car down a sewer, it’s actually going into a river poisoning fish,” Krantzberg said.

The study published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research said lessons learned from the remediation programs included the importance of meaningful public participation, establishing a compelling vision and clear goals in the early phases of the project, and establishing measurable targets for cleanups and focusing on Areas of Concern life after delisting.

Audrey Porter writes for Great Lakes Echo.