Fatma Alsaif spent the last semester of her senior year at Michigan State University hunting for jobs in the United States.

Like many foreign students who attend U.S. universities, Alsaif said she came to MSU to take advantage of opportunities she couldn’t get in her home country of Saudi Arabia. There, she could have selected only from gender-specific schools.

“Both my parents and I agreed on the idea of studying abroad,” said Alsaif, whose father and older sister also studied abroad. “So, it made sense for me to also go study abroad as well.”

Saudi Arabia was the fourth largest source of international students studying in the U.S. in 2017-2018, according to statistics from Institute of International Education. China, India, and South Korea are the top three.

But while thousands of students from these and other nations earn American educations, they face challenges staying in the U.S. to put those educations to work. U.S. college graduates from foreign countries face tightening immigration rules and high costs to get work authorizations.

Exploring opportunities in America

For Alsaif, who received her degree in media and information this month after living in the U.S. for six years, studying in America meant being out of her comfort zone and being fully independent. Though she doesn’t fully identify herself with American culture, she said she does feel a sense of belonging. She still misses her home sometimes

“Even minor things like pizza, it’s different than here,” she said.

Zhaoyu Zhang, a master’s student majoring in social work from China, studying in the U.S. was not his initial plan.

“It was more like a coincidence,” Zhang said.

During his senior year in China, he applied to several universities in Hong Kong and Australia and received some offers. Then one day, when a professor from MSU School of Social Work was visiting Zhang’s undergraduate academic adviser, an idea came to Zhang’s mind.

Courtesy of Zhaoyu Zhang

Zhaoyu Zhang, a Michigan State University master’s student from China, has faced challenges finding a U.S. company that will hire him for a summer internship. Last summer, he worked at the United Nations in New York.

“America is the cradle of social work,” he said. “Then I thought why not apply for social work programs in the U.S. instead of Hong Kong?”

In 2017, he received a full scholarship from China Scholarship Council. It included tuition, transportation, a living stipend and insurance for two years while studying in the U.S. The same year, he started his master’s program at Michigan State University.

Zhang doesn’t plan to work in the U.S. after graduation, but he’s hoping to gain more experience from summer internships in the U.S.

“I’ve already secured a position with World Food Programme in Rome after graduation,” Zhang said.

Last summer, he worked as a intern with United Nations at New York.

“The rent at NYC is high, but it worth the price,” he said, reflecting back his three-month stay in Manhattan. “Interns would get together after work for a drink every week, and we shared job opportunities with each other.”

Job market challenges

International students need approval from the U.S. government before they can work in the United States, either during college or after. That’s a disincentive for some employers.

“Most employers at career fairs I met will not favor students who need sponsorship to work in the U.S.,” Alsaif said.

One of the most commonly used work authorizations programs for international student is called Optional Practical Training, or OPT. The OPT program is directly related to the to an international student’s area of study. Eligible students can apply to receive up to 12 months of OPT employment authorization, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. For international students who receive a degree in a science, technology, engineering or math, or STEM, field, they can apply for a 24-month extension of the OPT period.

A record 276,500 foreign graduates received work permits under the OPT program in 2017, according to an analysis from the Pew Research Center. But growth in that program is slowing. The number of enrollees in OPT grew by only 8% in 2017, compared with 34% in 2016.

Part of that decline is due to fewer students in STEM areas, Pew said, although the Trump administration also is tightening program restrictions.

Alsaif is looking for internships and full-time jobs in Michigan. She said she cannot afford to move to big cities like New York or Chicago, where there are many open positions in her field.

“But then the question is, is a recent graduate ready to move to big cities?” she said.

Alsaif said it is stressful to find a job because companies are hesitant to sponsor international students. And there aren’t that many companies that accept recent graduates through the OPT program.

Zhang, too, said he had tried to find a job in the U.S.

“It’s hard to launch a job here in the U.S.,” he said.

One of his friends referred him a human resource internship at Michigan company, and several days later he got a Skype interview with a recruiter.

“The interview went quite well I guess,” he said. “But the last question she asked me was ‘Do you need sponsorship?’ and I said ‘Yes’.”

He didn’t get the internship.

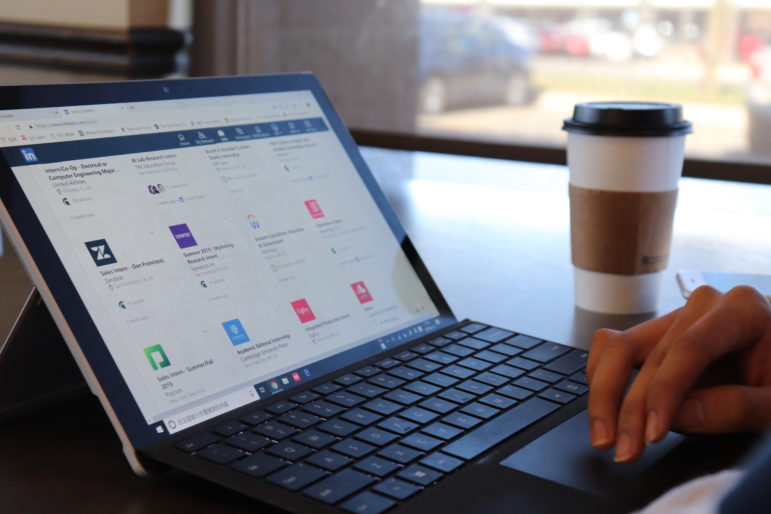

Crystal Chen

Zhaoyu Zhang searches for jobs online. He said getting a work authorization for a job at an American company made it harder to find jobs and internships.

Demand for work visas

After OPT, international students can apply for a H-1B visa, which allows a foreign national to work temporarily in the U.S. Once it’s approved, the duration of stay is three years with an extension to six years. However, individuals cannot apply directly for an H-1B visa. Instead, it is the employer who petitions and pay for it for its foreign employee.

Costs for an H-1B application vary based on the size of the company. According to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the cost ranges from $1,570 to $2,570 for employers under 25 full-time workers. For employers with more than 25 full-time workers, the cost can be $2,320 to $3,320.

“The cost is high for an employer,” Zhang said. “It’s understandable that a lot of employers are not willing to hire international students who needs sponsorship when it comes to H-1B petition.

“And even if the employer petitioned for H-1B, there’s no guarantee that the visa will be approved.”

Each year, only 85,000 are available, including 20,000 H-1B visas that are available only to workers with a master’s degree or higher from an accredited U.S. university or college.

The visas are awarded via lottery. According to Fragomen, an international immigration firm based in New York, H-1B applicants last year had a 38% chance of their application being granted.

The H-1B visa quota cap hasn’t changed since 2004. The U.S. received 190,098 H1B petitions this year.

The potential risks can hold employers back from hiring students and graduates from foreign countries.

“There’s no guarantee that an international student will be able to continue to work in the U.S.,” said Steve Tobocman, executive director of Global Detroit, a nonprofit that works to strengthen Detroit’s connections to the world to produce jobs and regional economic growth.

Tobocman said human resource department staffs are often more focused on risk mitigation and hiring without additional expense.

“All things being equal, most employers are going to opt for someone where there’s no risk of their long-time ability to work for the company that doesn’t require additional legal fees or having to hope that you win the lottery,” Tobocman said.

In addition to the risks involved in pursuing work authorizations, employers may also be worried about international students being pulled by family to return home.

Tobocman said he believes Michigan economy will have a competitive advantage when more employers begin to understand the talent that exists in international students. He said his organization is also work on other ways to try to make it easier for international students to find U.S. jobs and internships.

“Professional network is the biggest challenge that most students don’t pay enough attention to, and it’s something that international students can work on from the day that they arrived,” Tobocman said. “Companies, even big companies, hire people they know. They hire from trusted sources in hiring individuals, more than just a resume.”

Zhang also agrees that networking is important. He heard about the job openings with World Food Programme from an intern.

“His supervisor sent him a list of open positions at several international organizations and he sent it to me,” Zhang said.

Stay in the U.S., or return home?

For international students who hope to stay in the U.S. after graduation, the clock is already ticking.

Alsaif’s OPT period starts in July, which means she needs to secure a job before the end of September. She said she’s a little “picky” about the job.

“I don’t want to get any job,” she said. “And I want to get a job that helps me learn the industry and helps me grow.”

In recent years, Saudi Arabia started to support the film and media industry. The country is reopening theaters and cinemas.

“People now are taking the entertainment industry seriously,” she said.

Crystal Chen

Fatma Alsaif graduated in May with a degree in media and information from Michigan State University. She is looking for a job in the United States.

Alsaif wants to go back to Saudi Arabia “after a while.”

“I want to go home eventually. Not necessarily after a year or two. But after a while,” she said. “I don’t know what a while is, but I don’t want to go home immediately.”

For Zhang, he’s uncertain about where he will go after his yearlong contract position in Rome.

“I might go to courtiers in Africa or Latin America after that,” he said. “As a social worker, you need to go to front line, and it’s good for your career development.”

His parents want him to go back to China.

“My father keeps pushing me to come back home since they’ll soon be retired,” he said, “and they’re afraid if they got older and sick, who’s gonna take care of them?”