The ever-shifting landscape of college football has meant head coaches must adapt constantly. Currently, coaches must not only recruit players based on the luster of their program but also through a name, image and likeness.

Name, image and likeness, commonly referred to as NIL, gives players the ability to earn money off of their name. This is done through promotions and advertising. Many versions of NIL funds exist, but most are independent funds, separate from university affiliations. One of these independent NIL funds at Michigan State University is the new Spartan Nation Fund.

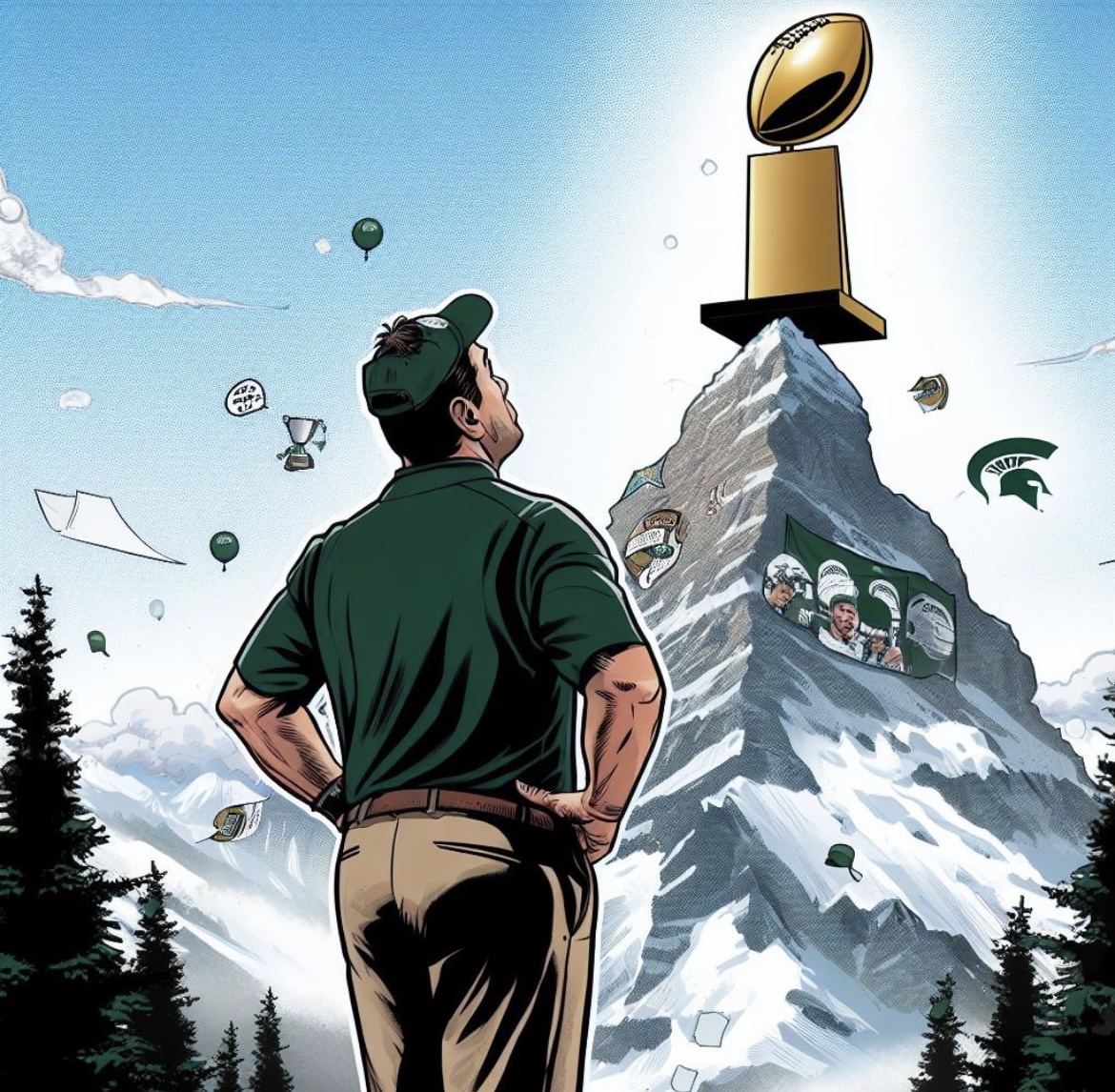

The Michigan State football program is entering their first spring under new head coach Jonathan Smith. Smith’s record as head coach at Oregon State has given the Spartan community something to be hopeful for, and that hope has brought new potential revenue for college athletes.

“I feel extremely excited and blessed to have someone like him who has shown he can take a team from a losing record and turn them into a championship team with bowl appearances,” said Jax Wilson, defensive end on MSU’s team. “I think he brings great knowledge of the game and an innovative offense to the table.”

Wilson chose to stay for the next season rather than transfer to another program due to the changing coaching staff. Wilson also has a sponsorship with JBL, one of the many NIL sponsorships with MSU players.

According to Sports Illustrated’s NIL tracker, most players make around $10,000 to $50,000 annually. They also noted that the top five players per roster are making more than $100,000 per season. The highest earner is Colorado quarterback Shedeur Sanders, who makes $4.7 million annually.

“If college football turns into something where they are just employees, then it’s just a pathetic version of the NFL,” said Mike Valenti, a Detroit sports radio host. “We don’t need that, it just doesn’t do anything for me.”

Sports commentators like Valenti, as well as other sports journalists, researchers, and coaches, have begun noting the way money has started changing the nature of college athletics.

“Maybe this doesn’t work anymore, that the goals and aspirations are just different and that it’s all about how much money I can make as a college player,” stated former Alabama football coach Nick Saban during a congressional hearing on March 11 about the topic of NIL and college sports. “I’m not saying that’s bad. I’m not saying it’s wrong, I’m just saying that’s never been what we were all about, and it’s not why we had success through the years.”

Saban, who many consider the best college football coach of all time, recently retired as the head coach at University of Alabama. Many sports commentators and fans alike have speculated that Saban retired because of the changing landscape and player motivations.

A 2020 legal analysis by a researcher at Fordham University noted that the O’Bannon vs. NCAA court case which legalized NIL income for college athletes has two sides. It stated that college athletes were legally owed compensation for the labor they provide to universities that make millions of dollars from their athletic programs. But it also complicates the student-athlete dynamic, and ultimately, implementations of the decision have “fallen short of their goal.”

While Johnson reportedly stands to make upwards of $52 million over the next seven years, NIL concerns for players seem to pale in comparison.