When it comes to school discipline in the United States, punishments such as detention, suspension and even expulsion are nothing new – but in recent years, proponents of restorative justice have become hopeful that for the most part, they may soon be left in the past.

Restorative practices – which Michigan schools have been required to consider as disciplinary alternatives since the signing of Gov. Rick Snyder’s restorative justice law in 2016 – focus primarily on overall harm reduction, and encourage schools to consider the full context of a situation when deciding on disciplinary measures.

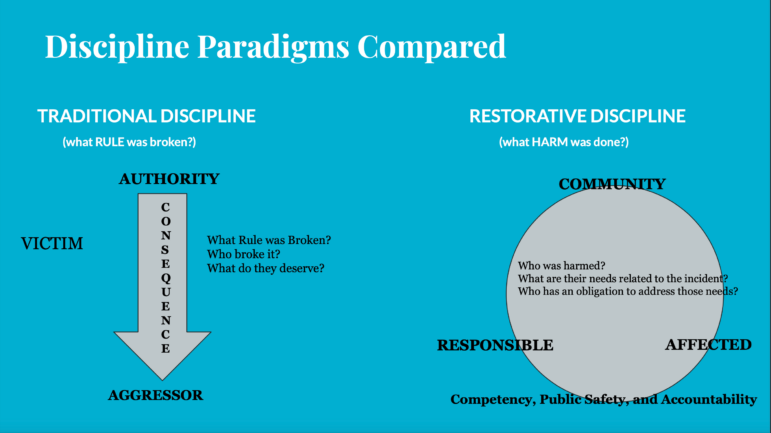

“It’s an approach to addressing conflict and misconduct that focuses on healing the harm rather than punishment, and that values accountability over exclusion,” said MacDonald Middle School Assistant Principal John Atkinson, who spoke about his school’s use of restorative justice at an East Lansing School Board meeting on Jan 22.

“Rather than relying on just punishment, restorative justice expects those who cause injuries to make things right.”

However, when it comes to how these amends can be brought about, schools have found that there is no one right answer.

“It looks different everywhere, and I think that’s because a lot of schools have been shifting more towards restorative practices in general,” said Adam Brandt, an assistant principal at Eaton Rapids Middle School. Brandt, who became one of the school’s assistant principals in July of 2022, believes that one of the core aspects of the process is the intentional fostering of respect and acknowledgement between students and staff – and at Eaton Rapids Middle, this starts with a social contract, which teachers and students work together to create.

“You can reference that throughout the year and be like, ‘hey, are we following our contract that we agreed on in the beginning of the year?’” said Brandt. “[You can ask] ‘How do you want this classroom to look? What is something that we would all appreciate?’ And honestly, most times it all comes down to respecting each other.”

Amy Martin, the principal at MacDonald Middle School, couldn’t agree more.

“It’s not just conflicts with kids, right? We as adults also participate in the process, and it’s really [about] giving everyone an equal voice and feeling heard and respected.”

Martin, who inherited a significantly less-developed version of MacDonald’s restorative justice system when she first joined the school, largely credits the system’s recent success to the full-time presence of the school’s restorative justice coordinator, Adeline Alderink (affectionately known by students and staff as “Miss Addie”).

“Having someone dedicated to the process that’s trained in restorative practices, that that’s their priority and that’s their number one job, that’s going to be kind of a must if you’re going to really implement RJ with fidelity,” said Martin. But it’s not just Alderink’s presence that makes things work – it’s also the positive relationships she’s able to foster with the students she works with.

“Miss Addie is very well liked by the students, and they seek her out,” said Martin. “So I think it also depends on the person that you have in that role – because if you have the wrong person in there, it’s not going to work. So you need the right person, that students are going to relate to, and have a relationship with.”

Additionally, Martin describes MacDonald’s restorative justice system as not only a means of discipline, but also as an opportunity for students to take the initiative to peacefully solve conflicts amongst themselves.

“They met with [Miss Addie], and she didn’t even have to run the circle,” said Martin, describing a recent situation in which two boys had asked Alderink to mediate a disagreement between them. “They just knew the process and worked it out, and just wanted a space where they knew that they both will be heard and respected in that environment.”

And when it comes to mediating issues between students and teachers, restorative practices can often be just as helpful. At Eaton Rapids Middle School, for instance, students who exhibit disruptive behaviors in class are typically sent to a room known as the Responsible Thinking Classroom (RTC), where they are then guided through the process of coming up with a plan to remedy and make amends for their behavior.

“When they come in, we have someone there who is trained in this, and they give the students what’s called a responsible thinking plan,” said Brandt. “And that’s where they then review what happened in class. ‘How did that affect others? How did that affect myself? What are some strategies or a plan that I can create moving forward to go over with my teacher to be then let back into class?’”

Then, the student must meet with their teacher, where the two of them will go over the plan together. “[The teacher might say] ‘Okay, I like this plan,’ or ‘You know what? There’s some weaknesses in this plan,’” said Brandt. “Either way, they work through it. They talk through it, and then they’re like, ‘okay, you can come back into my class today and let’s try again.’”

However, while restorative practices can – and often do – have an overall positive impact on the schools in which they’re implemented, Martin warns against relying on them too heavily, especially in the beginning.

“It’s not perfect. I mean obviously there’s times when conditions aren’t met, and we have to go more of the punitive route,” said Martin, recounting her school’s initial struggle to find a balance between restorative justice and more traditional discipline methods. “I mean, John and I can probably talk to any school about [how] we’ve seen articles like ‘RJ ruined our school’ — well, it kind of almost ruined ours too, because we leaned too heavily on that when we didn’t have other or traditional consequences in place.”

But with a good combination of discipline methods now established, Martin’s next goal is to improve communication with families, and to provide them with the opportunity to learn more about what restorative practices mean for their students.

“Often times, especially when families come in and something’s happened to their child, they want to know what’s going to be done to the other student who harmed their child,” said Martin. “And I think that we just need to educate our school community, our families, [our] parent community, that this is the approach that we use when possible, [but it] doesn’t mean that we also don’t use more of a consequence.”

Brandt also hopes to increase family outreach, and is eager to educate parents and families about the ways in which restorative justice is impacting their students’ lives.

“I think it’d be nice for the community to know more — that we actually are doing a restorative process,” said Brandt. “Because I think a lot of parents, you know, they come from a time… where if you got sent out of the classroom, it was always punitive. It was always discipline. It was never a process, it was always, ‘No, you’re just in trouble.’ And I think that’s a lot of times how parents first react, before they understand what it is.”

Brandt also acknowledges that this lack of knowledge about restorative justice often goes beyond just parents, and posits that other schools may find it intimidating to initiate the shift to restorative practices, especially if it is a concept they’ve only recently become familiar with. But though the prospect of such a major shift may be daunting, his advice to them is ultimately simple: don’t overthink it.

“It doesn’t have to be as complicated as we may make it in our own heads,” said Brandt. “We gotta stop thinking of it as a daunting task, and more of something that we can implement pieces of, and eventually build something over time.”