Asterra

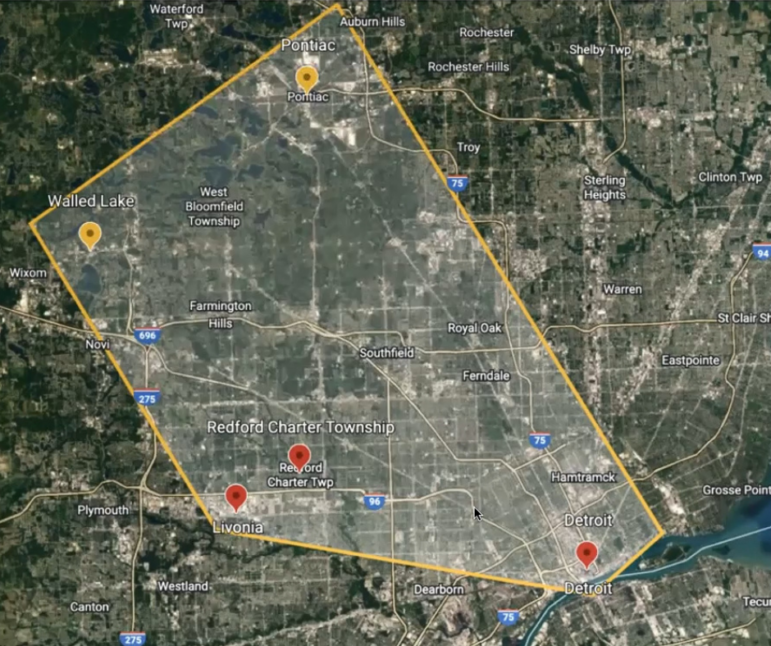

Map of an area scanned by SAR technologyBy VLADISLAVA SUKHANOVSKAYA

Capital News Service

LANSING – The radar technology developed to find water on Mars is cheaper and more effective in detecting leaks in public water systems compared to traditional ones. And now it has arrived in Michigan.

The Great Lakes Water Authority is doing a pilot project in collaboration with Asterra, an Israeli company, to get data on water leaks and share the results with other municipalities.

Communities that already participate in the project are Detroit, Livonia, Pontiac, Redford Township and Walled Lake.

The company used synthetic aperture radar or SAR on a hundred to a couple of hundred miles of water lines in each place: 600 miles in total.

The authority draws water from Lake Huron and the Detroit River and provides water to parts or all of Wayne, Monroe, Macomb, Oakland, St. Clair, Genesee, Lapeer and Washtenaw counties.

Eric Trerotola, Asterra’s sales manager for North America, explained the water loss numbers and how the company employs satellites and artificial intelligence to detect leaks.

Every year, U.S. water systems lose 2.1 trillion gallons, Trerotola said, the equivalent of “33 days of continuous flow of Niagara Falls.”

Waste of electricity and treatment chemicals is tied to loss of water too, and that costs billions of dollars annually, Trerotola said.

He added, “Leaks don’t fix themselves. They either persist or they get worse.”

Now Asterra employs SAR in 64 countries.

The company says it has so far saved over 368 billion gallons and found over 100,000 leaks worldwide.

Traditionally, utility companies find leaks by walking their entire system and looking for drops in pressure, “listening” to pipes and putting boots on the ground to find and repair leaks.

Listening to leaks is literal. Leaks create high-pitched noise that gets picked up by sensors – ground microphones, said John Norton, the director of energy, research and innovation at the Great Lakes Water Authority

The sound travels through metal pipes and the frequency changes, depending on how far away listeners are from the leak.

Trerotola said, “They have to go listen, and it’s painstaking, hundreds of miles.”

SAR works differently. It starts with taking fresh images of the Earth with several satellites going orbiting it every 90 minutes.

Satellites send a radio signal out and pick it up when it is reflected from the surface. Trerotola said it’s similar to dolphins using sonar and bats using echolocation.

Pipe materials have different properties, as do different types of water. Looking at it, experts can tell what is potable water and what is wastewater.

That’s how SAR can “see” a water leak even in the middle of a tidal marsh.

Artificial intelligence analyzes the data and shows where it is on the map. Then that image is overlaid on a map of the utility company’s pipes.

Trerotola said it shows all of the utility’s pipes, valves, hydrants and meters.

After that, actual people must verify and fix the leaks, but the area they need to walk is much smaller – a 330-foot radius, Trerotola said.

He added, “Rather than them walking up and down all of the areas, we highlight 5% to 10% of the overall system’s length.”

In one of its projects in Arkansas, Asterra found 14 times more leaks in less working time than the traditional search system did. The cost to find a leak was $678 each with SAR, compared to $14,130 for traditional detection.

Right now, Asterra and the authority are working together in Detroit, Livonia, Pontiac, Redford Township and Walled Lake. Crews from each municipality learn additional skills in leak detection on the ground.

The approximate cost of the project is $90,000, according to Norton and Trerotola. The funding comes from the authority.

Asterra also sends experts to work with detection crews on the ground. The company wants to complete its field investigation by the end of November before it becomes too cold.