The East Lansing Independent Police Oversight Committee recently held a workshop to gather input from residents on what actions the East Lansing Police Department should take to “minimize use of force and eliminate its disproportionate use with people of color.”

The workshop, led by seasoned facilitators Carlton Evans and Doak Bloss, was meant to generate ideas from residents which, after being compared with ELPD’s current policies, will be converted into concrete policy recommendations by ELIPOC. A subsequent meeting on Nov. 1 will be held to ensure those recommendations reflect the wishes of the community.

During the meeting, members of the community worked in small groups to create policy goals which were then presented to the meeting. The most common suggestions included emphasizing de-escalation practices during training and a stronger system for internal accountability within the police department.

Emilio Perez Ibarguen

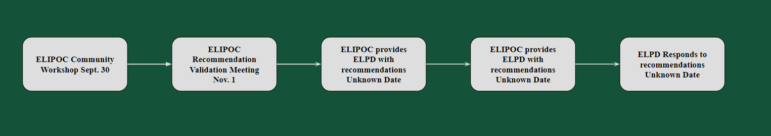

Illustration depicting the necessary bureaucratic steps for community proposals from the ELIPOC workshop to become policyEast Lansing resident Merry Stanford said she views the power dynamic between police officers and civilians as unequal and ripe for abuse.

“I’ve come to understand that if the police view you as a victim, they will be helpful,” Stanford said. “But if they view you as a violator, they’re going to be threatening and attempt to dominate you.”

According to ELIPOC’s annual report for 2022, ELPD’s use of force demonstrated “significant racial disparities,” noting that despite making up only 6.8% of East Lansing’s population, Black people were involved in 56% of use-of-force incidents. ELPD internally defines these incidents as whenever an officer’s use of force rises above “cooperative handcuffing.”

Emilio Perez Ibarguen

ELIPOC Chair Erick Williams discusses potential policy initiatives with other participants at the Sept. 1 workshopAdditionally, various participants of the workshop said they wish for the commission to tackle the culture issue within the police department. Some argued that, regardless of what policy changes are instituted, change cannot occur until bad actors are not able to skirt accountability for unethical behavior.

East Lansing resident Joshua Hewitt likened police culture to that found within the sales industry, where ethics take a backseat to high performance. Even if not explicit, Hewitt added, poor police culture will discourage honest recruits from rising the ranks.

“If you’re a good police recruit, and you go into the police force, and the culture is somewhat unethical, it’s hard,” Hewitt said. “You either buy into it, or you butt heads with the police chief, or you leave.”

Cedrick Heraux, a member of the Study Committee for ELIPOC and an associate professor of criminal justice at Adrian College, attributed the source of poor police culture to the fact that police officers are often taught to always expect the worst from an interaction with a civilian.

“In training, (officers) are reinforced with the idea that at any given moment, the worst possible scenario could occur,” Heraux said. “We train officers something like nine times more often in terms of firing their weapons than in de-escalation. But the average officer will never fire their weapon.”

Following the workshop, ELIPOC Chair Erick Williams said he was optimistic that the ideas brought to the table would result in concrete policy changes.

“It’s always productive,” Williams said. “It’s important to have people come in and put their heads together.”