The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

By MORGAN WOMACK

Capital News Service

LANSING – Mid-May is hunting season for Brendan Earl and his team. In place of weapons, they’ll drag large, textured cloths along fields, trails and forest floors.

Big game isn’t what they’re after, it’s tiny ticks: little parasites known for spreading diseases.

And Earl said he’s expecting this tick season to be much worse than the last few seasons because of the mild winter. The warmer temperatures could have allowed ticks to overwinter under leaf litter and survive.

Earl, who is a supervisor sanitarian for the Kent County Health Department, calls these surveying trips “tick drags” — a method used by researchers to collect ticks. They take them back to the lab to test which species might carry diseases. The results from testing are reported to the public to let them know which species to look out for.

“We do tick drags in areas of the county that a lot of people might encounter,” Earl said. “We can identify different types of species that inhabit those areas and then look for some of the ticks that may carry vector-borne diseases like Lyme disease.”

Black-legged ticks, commonly known as deer ticks, can carry Lyme disease, an illness that can be transmitted to people through tick bites. It can manifest in a variety of symptoms including a rash, flu-like symptoms and joint and muscle pain.

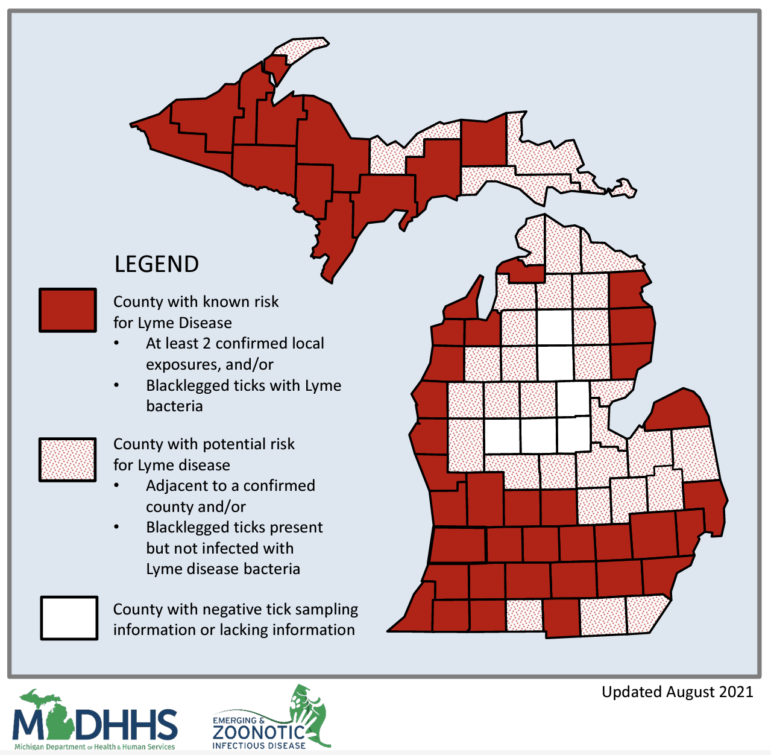

There were 864 reported cases of Lyme disease statewide in 2021 and most exposures occurred in the Upper Peninsula and western Lower Peninsula, according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

All but six Michigan counties have been identified by the department as having a risk or potential risk for Lyme disease.

“We just want to let everyone know that it’s extremely worse than last season and know the proper way to protect yourself from tick bites,” Earl said.

Members of the Kent County Health Department annually distribute materials providing information on tick-borne diseases and safety. They put out signs and attend various festivals, concerts and movie nights to spread the word.

Earl said people exploring nature, specifically in high grass or woodland areas, should wear bug repellent and light clothing — so it’s easier to spot ticks crawling.

“A lot of people get nervous or scared, but we don’t want that,” Earl said. “We want people using the outdoors. It’s just (important) to be cognizant and have a reminder of these little things you can do to prevent the spread of vector-borne diseases.”

Emily Dinh, a medical entomologist at the state health department, said people who visit grassy or forested areas should monitor themselves for Lyme disease symptoms for about 30 days afterward.

Dinh said the black-legged tick can be active for 10 to 12 months out of the year, or anytime the weather hits 38 to 40 degrees or higher.

The first layer of protection against tick bites is clothing, Dinh said. People should wear long pants and sleeves and tuck in clothing that might expose any skin. Repellents add another layer of protection. After hiking, they can put their clothes in the dryer for about 10 minutes to kill any stragglers.

Then, Dinh recommends scanning the body for ticks, especially crevices like the belly button, hairline and joints. American dog ticks are also a commonly encountered species, but are larger and easier to spot than deer ticks, which can be the size of a black pepper flake.

To remove a tick, grab as close to its head as possible and use gentle, firm pressure to pull up. Michigan residents can send in photos or mail their capture to the health department by visiting michigan.gov/lyme.

“There’s a lot to be done on trying to understand ticks and Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases in Michigan,” Dinh said. “That’s one effort that helped contribute data into our Lyme disease risk map that we update every year.”