I woke up on the morning of Feb. 13 with my mind moving a million miles a minute.

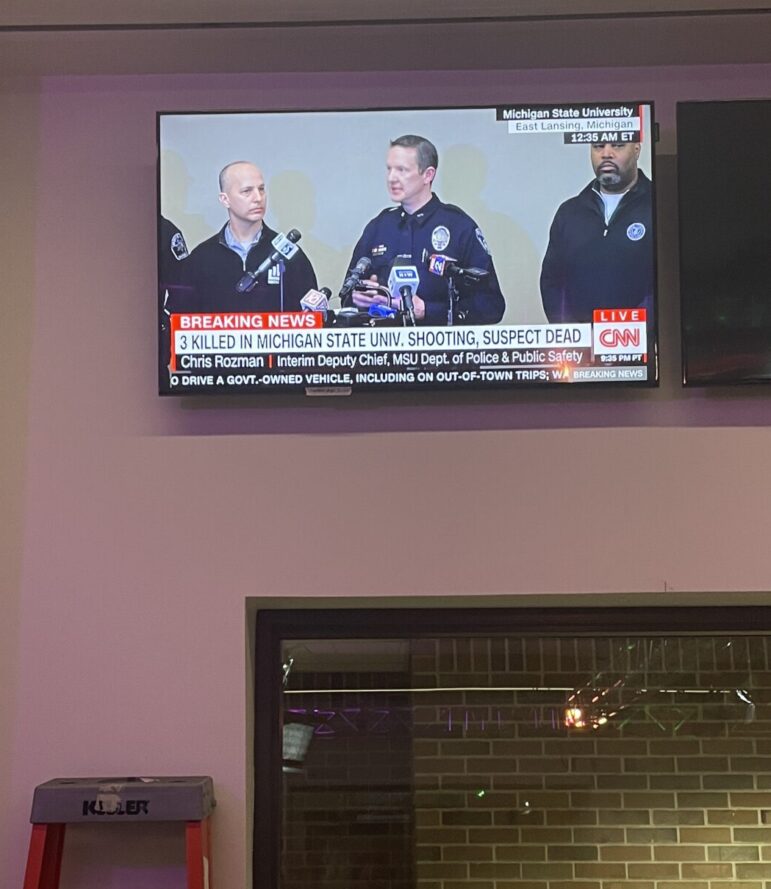

Jason Laplow

A TV in the newsroom reports of the shooting at Michigan State University in the early morning of Feb. 14.I was used to it at that point. Ever since the new semester started, my life and responsibilities had felt like a snowball constantly rolling down the side of a mountain, picking up speed and mass along the way, with a big crash imminent. Juggling classes, work, and extracurriculars as a sophomore at Michigan State University was proving to be difficult for me. I’d called my mom just a few nights earlier and begun to cry.

I needed a break.

Fortunately, I had a break built into my schedule that night. Monday nights are a special time for myself and dozens of other student journalists who have an interest in sports. I direct the Spartan Sports Report, a SportsCenter-like show that showcases MSU athletics. We have a very talented, dedicated, and friendly group of students who make the show the best it can be. Additionally, in between editing, script writing and filming, Monday nights are a time when we all get to hang out and socialize.

On the night of Feb. 13, the team was ahead of schedule. This was the third show of the semester, and for the first two shows, we had to stay in the newsroom until at least 10 p.m. But this time, we were wrapping up at 8:40 p.m.

It was customary for the crew to clap when the filming finished. But when I started to clap this time, it sounded like almost no one was joining in. I hadn’t looked at my phone for the last 30 minutes. Everyone else, it seemed, knew something that I didn’t.

Our advisor, Professor L.A. Dickerson, opened the door and remarked that there was “a situation” at the Union and that we needed to move across the hall immediately to shelter in place. I looked down at my phone. A message from the MSU alert system told of an active shooter on campus.

As we all filed into the room, which was chosen by Dickerson because of the fact that it had a piano that could be used to barricade the door, the mood didn’t really change. We had all been through active shooting drills before, and despite the fact that we received a message declaring “Run, Hide, Fight,” everyone seemed to not be alarmed for the first few minutes until the communication with the outside world really began to ramp up.

It seemed like everyone I knew was texting me. All of the things I had woken up worried about suddenly seemed so trivial.

What’s going on!?!?, my mom texted me.

I don’t know, I replied. I was filming a show and now we are sheltering in place.

I thought back to just a year prior when there was a deadly shooting at Oxford High School. An article I read had documented some of the text messages that students sent to their loved ones as they were hiding and fearing for their lives. The messages I was sending and receiving began to look eerily similar. I began to hear constant sirens and the occasional helicopter whir overhead. We shut off all the lights and laid on the floor.

Zach Beavers, another student director, was a few feet away from me. As I was frantically scanning through my Twitter feed looking for any sort of updates, I read a tweet that he had just posted:

As Beavers alluded to, he really had been “here” for 23 years. He was born and raised in the Lansing area before beginning his studies at MSU. He commutes to campus from his family home, less than 15 minutes away. This was affecting his true home, not just the place he goes to school.

“This is literally my home,” Beavers said. “You list all the places that have been affected by something like this. Michigan State’s always gonna be there. East Lansing’s always gonna be there.”

Beavers, a senior studying journalism, shared that he feels as though he’s been “running on borrowed time” throughout his time at MSU, largely due to the pandemic. He felt like the world was rushing around him before the shooting took place, trying to cram four years of the college experience into just two years, and the shooting had further set things back.

He had felt a sense of guilt lately. A lot of other people I know have had feelings of guilt, too, including me. The random nature of the shooting meant that anybody could have been in Berkey Hall or the Union at that time.

My mind began to think, “Why not me?”

As the night pressed on, so did my anxiety. Messages were constantly soaring in and out of my phone. Many of them were directed to my roommate, Charlie Hunkins, who was playing basketball at the I.M. Sports East building when the shooting took place.

Emergency dispatchers on the police radio, which nearly everyone in the room was listening to via scanner apps on their phones, indicated that callers were reporting they heard shots fired at his exact location. I’d later learn that these reports were inaccurate, just scared students reporting every loud noise they heard out of fear. But for an agonizing ten minutes, I waited for a response from Hunkins. For ten minutes, as the message read simply “Delivered,” I began to accept that I could have lost my roommate.

“I was ready to die,” Hunkins later told me.

I thought I’d lost him. We grew up together. We’d been best friends since kindergarten. Accepting that he could have been hurt or even died was probably the most trauma that I experienced the entire night.

During the ten minutes that he didn’t respond, he had been evacuated from the building by police officers wielding rifles. He was then escorted across the bulk of the campus to Landon Hall, where he was staged with many others.

My girlfriend, Hannah, who was an hour away, had been texting with me all night. Little did I know that she was in and out of a constant cycle of tears while fearing for not only me, but also her best friend, Grace, who could see the Union from the window of her dorm room at Campbell Hall.

After sitting on the ground in a dark room for over four hours, Hannah told me that she had heard police state on the scanner that a possible suspect was located miles away from campus. As I looked up from my phone, it seemed like everyone in the room listening to the scanner must have heard the same news.

When we got back to our dorm, Hunkins and I decided to immediately drive back to our hometown of Midland about an hour and a half away. We packed our bags in just a few minutes, got in the car and drove.

I woke up the next morning with a completely different set of worries on my mind than the day before. I didn’t get out of bed for hours. Beavers said he had a similar experience. We didn’t have any energy.

My girlfriend drove to my house that night. As she embraced me, I broke down in tears.

I was thinking about how those who were shot probably woke up thinking about the same things I had. They were just college students trying to better their lives. They could have woken up with homework on their minds just like I did.

Five of them would wake up the next morning in a hospital bed. Three of them would never wake up again.