“What are you willing to pay for change? What have you paid already?”

Lisa Jackson spoke as if she was presenting off the cuff. Her voice echoed slightly over Zoom in Ann Arbor City Council chambers.

Jackson wears many hats in her day-to-day life – she teaches psychology at Schoolcraft College, researches neuroscience and keeps tabs on her two adult children. She’s also the founding chairperson of Ann Arbor’s Independent Police Oversight Commission, a role she stepped down from in October after serving nearly three years.

On Sept. 6, Jackson was providing her last monthly update as chair to Ann Arbor City Council on the state of police oversight locally and nationally. She reviewed the commission’s accomplishments, then listed the names of people killed by police in June 2022 nationwide. It took her two and a half minutes to get through the list.

Jackson’s quick presentations are “somewhere between a TED Talk and a lecture and a sermon,” said Kevin Karpiak, a professor at Eastern Michigan University and director of the Southeast Michigan Criminal Justice Policy Research Project, which works with the Ann Arbor commission to research criminal justice policy and oversight.

“Early on, I recognized her ability as a leader, as a speaker, as someone who’s able to kind of set the terms of a conversation really powerfully,” Karpiak said.

Elinor Epperson / Spartan Newsroom

Lisa Jackson’s name card sits in city council chambers at Guy C. Larcom Jr. Municipal Building in Ann Arbor. Jackson was the founding chairperson of Ann Arbor’s 11-member Independent Community Police Oversight Commission, which meets monthly.Born in Louisville and raised in Detroit in the 1960s and ’70s, Jackson described her upbringing with fondness.

“I grew up with a Black mayor in a largely Black city,” she said. “It was like living in Black world.

“It was really affirming. I don’t think I really understood, maybe, that the world would ever see me differently until I was older.”

Her mother kept house and worked in banking, while her father was a social worker and therapist.

“That was just a normal thing for us,” she said. “An aunt would come over and babysit all of my cousins and my mom and dad and other aunts and uncles would go off and work at night.”

She said their work continued after hours, when they volunteered at “street schools” in burned-out buildings the 1970s. They would teach adults topics such as reading, writing, voting rights and how to handle interactions with police.

“Volunteering has always been a big thing in my life,” Jackson said.

She estimated she spends almost 40 hours per week on work for the oversight commission – on top of her regular job.

“I liked her right off the bat,” said Frances Todoro-Hargreaves, the oversight commission’s new chair.

She has worked on the commission with Jackson since its inception in 2019.

“She is always working,” Todoro-Hargreaves said. “She definitely brings a great presence and a great passion to it.”

Ann Arbor’s commission began meeting in 2019. Its 11 members review complaints made against the city’s police officers and make recommendations to City Council and police leadership on how to improve communication and trust between police and community members. They meet monthly at Ann Arbor’s city hall.

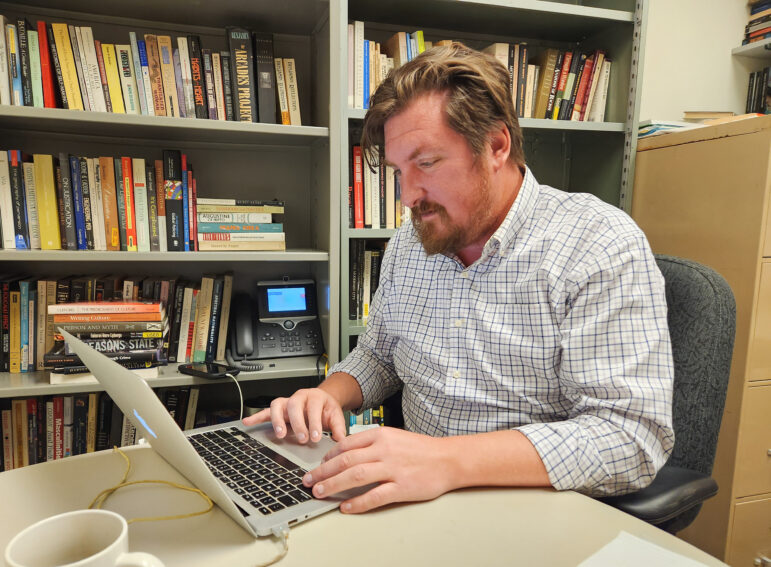

Elinor Epperson

Kevin Karpiak, professor in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminology at Eastern Michigan University, reviews data about police officer mental health in his office. Karpiak is working with Ann Arbor’s oversight commission to analyze traffic stop data from the Ann Arbor Police Department.“Police oversight commissions are nothing new,” Karpiak said. His current research project, studying the structure of community police oversight commissions across the United States, includes a commission that dates back to 1885.

“They’ve become really popular in the last 10 years or so,” he said. “There’s been a real explosion.”

According to a report from the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement, the number of civilian oversight commissions grew 39% between 2010 and 2019.

Ann Arbor’s commission “very rarely (talks) about specific cases,” Karpiak said. “It’s more about bigger visions of what public safety could look like.”

This larger vision includes an unarmed emergency response team in Ann Arbor, the reason the commission originally formed. Jackson learned the value of such a resource as a child.

“We had an extra phone in our house that was red,” she said. “The red phone would ring and no matter what time of day and night my dad would go out. If there was somebody threatening to commit suicide and the police were there, he would be the person – not the police – dealing with that person.”

In the years since, police have increasingly become the primary responders when people call 911 for mental health crises. Calls for mental health emergencies are also growing in frequency. One such call came to Ann Arbor police in November 2014.

Less than a minute after entering the house in question, an officer shot and killed resident Aura Rosser, 40. Police cited self defense, saying that she charged them with a knife. Rosser, who was Black, had a history of mental illness.

“That’s what has happened so many times,” Jackson said, referring to incidents where police have shot and killed someone who was in distress. “And that’s what’s so painful.”

Instead, she said, cities should provide an emergency response where “shooting a person in trouble is not an option.”

Ann Arbor has taken steps towards establishing such a program. In April 2021, City Council directed the city administrator to develop an unarmed emergency response. But Jackson and Todoro-Hargreaves said progress has been slow.

Like other commissions in the city, police oversight has no legal power. City Council and the police department are not required to follow the commission’s recommendations. Jackson and Todoro-Hargreaves said the commission has fought for years to get unredacted files and data for civilian complaints against police.

Just getting the monthly spot at City Council meetings was a fight, Jackson said.

“It’s been a constant battle, so anything that we have now has been a total accomplishment,” Todoro-Hargreaves said.

Karpiak said the commission “has very strong soft power. It’s very hard, I think, in the current moment to ignore them or not follow a recommendation that would be made. You better have a good reason.”

A map of civilian police oversight boards in Michigan, including when they were founded. According to a report by the Department of Justice and National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement, these boards act as “independent and neutral” watchdogs of local police departments. There are seven oversight boards operating in Michigan, with 2 more proposed.

Jackson isn’t sure how long she’ll stay on as a member. According to the city ordinance, commissioners may serve for up to six years, so she could serve another two years.

“If the commission needs me, I’m open to that,” she said. “But I’m also open to being replaced by somebody new who’s willing to bring some fresh blood in there.”

In 2020, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer appointed Jackson to the Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards. She is one of three community members on the state commission, which previously only included law enforcement officials. She also works with the Coalition for Re-envisioning Our Safety, a group of community members focused on creating an independent unarmed emergency response team.

Even as she adds more hats, Jackson said giving up is not an option.

“I know my ancestors endured far more than challenging bureaucratic obstacles to vote, to do things like that, that I have no right to not persist,” she said. “I don’t have the right to give up. And I feel that very strongly in my bones that if I have the privilege to fight this fight, then I am obligated to do it.”

Police Oversight in A2 By Elinor Epperson