By ERIC FREEDMAN

Capital News Service

LANSING – When it comes to freedom of expression, students are like other Americans – divided.

Students are divided about how much First Amendment protection they have to speak freely on their own campus, whether colleges and universities should ban racial slurs and whether they feel uncomfortable or unsafe because of what somebody else said about their race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation or gender.

Student attitudes are divided by race and ethnicity, by political orientation and, to a lesser degree by gender.

But overall, they increasingly say speech rights are less and less secure than in the past.

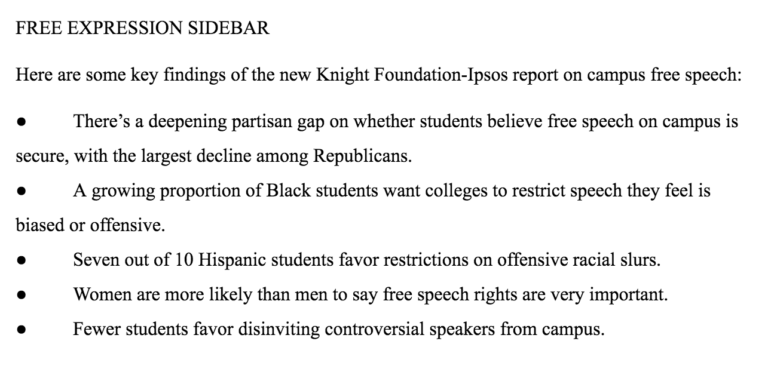

Those are troubling key take-aways from a new study by the Knight Foundation and the market research firm Ipsos.

“College campuses have long been places where the limits of free expression are debated and tested,” according to the study based on a national survey of more than 1,000 students.

The COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 presidential election and the racial justice movement have influenced the dialogue about free speech both on campuses and in wider American society, it says.

“This survey reinforces that students are not a monolithic group when it comes to speech,” the study says. “Partisanship, race and ethnicity drive meaningful differences on how college students view speech.

“Understanding where different groups stand is vitally important for higher education leaders as they seek to foster free expression and create a campus environment that is diverse, equitable and inclusive,” it said.

First Amendment protections for free speech apply only in public institutions, such as public community colleges and state colleges, but not on private campuses.

The most recent controversy in Michigan erupted when Ferris State University suspended history professor Barry Mehler with pay for posting a video describing students as “vectors of disease” and using profanity while talking about his plagiarism policy. A university statement described the video as “profane, offensive and disturbing.”

A federal judge has rejected Mehler’s bid for immediate reinstatement in a federal lawsuit that accuses Ferris State of violating his First Amendment rights.

Earlier, in 2018, fights erupted and arrests took place when white supremacist Richard Spencer spoke at Michigan State University.

Press reports at the time said Spencer’s remarks included comments that alt-right groups draw more hostility than groups like the Nation of Islam and Black Lives Matter and that whites are becoming a minority in America.

Elsewhere around the country, a number of controversies involving free expression at public institutions have drawn recent media attention.

For example, a federal judge ruled in January that efforts by the University of Florida to prohibit professors from testifying in a voting right case were unconstitutional. The university unsuccessfully argued that it is a conflict of interest for faculty members to serve as expert witnesses in lawsuits against the state.

Also in January, a Texas community college agreed to pay $70,000 in damages to a professor it fired for “insubordination” because she had tweeted that a moderator in a 2020 vice presidential debate should “talk over Mike Pence until he shuts his little demon mouth up.” Collin College agreed to the payout to settle ex-professor Lora Burnett’s First Amendment lawsuit.

But the same month, the same college fired another history professor who claims he was terminated for “speaking out about a topic that the college’s leadership didn’t like,” namely a student assignment about the history of epidemics and pandemics from the time of Christopher Columbus to COVID-19, the Chronicle of Higher Education reported..

And last December, the state attorney general asked Louisiana State University to punish a journalism professor for calling an assistant attorney general a “flunkie” in a tweet. Professor Robert Mann sent the tweet after the assistant attended a university faculty senate meeting to read her boss’s letter calling COVID-19 vaccine mandates “problematic” and a violation of religious freedom.

Overall, the Knight Foundation-Ipsos study found that students feel it’s important to be exposed to a wide spectrum of speech on campus but that they also have serious concerns about the actual and desirable degree of free expression allowed there.

Their beliefs sometimes appear in conflict. As the study said the students increasingly say the campus climate “prevents some from saying things others may find offensive, and fewer feel comfortable disagreeing in class.”

On the other hand, the survey found that slightly more students claimed to feel unsafe due to remarks made on campus last year than in 2019, especially students of color and women.

Eric Freedman teaches journalism at Michigan State University where he is the director of Capital News Service.