By ERIC FREEDMAN

Capital News Service

LANSING — The bees are coming! And so are the hairy maggot blow flies!

Both had already come uninvited to Michigan. And now there’s proof they’re continuing to spread in the Great Lakes region.

The wrong-place bees are leafcutters — and they don’t belong in Chicago, the first place they’ve been identified in Illinois.

Northwestern University.

Non-native female leafcutter bee found in Chicago. The invasive species has been spreading inward from the East and West Coasts.Where they do belong is Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Introduced accidentally to North America, they appear to be rapidly spreading “inward from both the East and Western coasts,” according to a new study by researchers at Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden.

Scientists found 30 of the leafcutter bees near the Clybourn Metra train station, about 3½ miles from downtown Chicago. Their presence was previously confirmed in Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

As for the hairy maggot blow fly, its presence has been confirmed in Indiana for the first time, a separate new study says.

The Australian native arrived in Costa Rica in 1978 and spread into North America, including the Great Lakes states of Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin – and now Indiana.

Valparaiso University researchers identified the invader in a remote part of the campus, about 50 miles southwest of St. Joseph. That’s where biologist Kristi Bugajski teaches forensic science students about the decomposition of bodies.

Hairy maggot blow flies feed on dead and decaying tissue. Forensic scientists use them to estimate time of death.

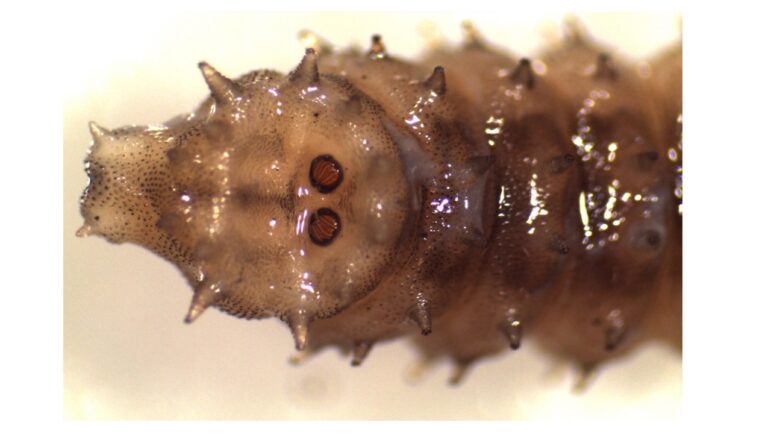

Valparaiso University.

Hairy maggot blow fly collected in Valparaiso, Indiana. The invasive species has been found in Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin and now, Indiana.Bugajski first spotted them where she’d set up a couple of dead pigs in the research area.

“I got really excited,” she said. As for her students, “They didn’t quite share my enthusiasm.”

Is there cause to worry?

“Nonnative species can have detrimental effects on native ecosystems, yet the consequences are generally unknown, especially for unintentionally introduced species,” the bee study said.

And invasive insects can create major problems, according to Scott Lint, a Michigan Department of Natural Resources entomologist.

To illustrate, the emerald ash borer has killed tens of millions of ash in Michigan. And the destructive hemlock woolly adelgid has appeared in the western part of the state,

“They’re unimpaired in their ability to cause damage, at least during the initial infestation because our plants (that they feed on) have no natural defenses against these new species,” Lint said.

An upcoming worry: the spotted lantern fly, an Asian native predicted to arrive in Michigan from Pennsylvania “probably not too long” from now, Lint said.

“Our biggest concern is pretty much the human pathway,” he said, noting, for example, that the invasive gypsy moth spread by laying its eggs on campers and railroad cars.

The bee study said the leafcutter’s discovery in a heavily urbanized part of Chicago suggests it’s “fully capable of taking advantage of extreme, urban environments,” and its apparent preference for nonnative plants “suggests it may be able to flourish in highly disturbed areas.” It feeds on common spotted knotweed, another invader.

“Although we do not know the extent of the impact of nonnative bee species, there is evidence they may compete strongly with native bees for nesting resources,” the study said. “As urbanization continues to grow worldwide, it is important to monitor the spread of nonnative bee species to help us determine the potential impacts they may pose on native species.”

Lead author Andrea Gruver said it wasn’t surprising to find Illinois’ first known members of the species in Chicago, given the spread of nonnative insects across the United States.

How they got to Chicago is uncertain, however.

“We don’t really know how far really small bees can potentially fly,” said Gruver, a graduate student in plant biology and conservation. Possible explanations including being accidentally carried in pollinator nesting tubes of another bee species, or possibly they “nested in some structure that got here and woke up in Chicago.”

As for the congested urban setting of its discovery, she said, “We see more nonnative bees in highly urban areas and cities and fewer native species.”

Now back to the hairy maggot blow fly.

How it reached Indiana is also uncertain, Bugajski said. Possibilities are hurricanes or other “weird weather patterns,” warming temperatures that let them spread – or “they have been here for a while and nobody found them.”

Her study expressed concern that it could outcompete native species of blow flies.

However, it said the invader isn’t expected to have a large effect because Northwestern Indiana’s native species prefer warm weather and typically aren’t around in the fall, when the invader is present.

Both studies appeared in the journal Great Lakes Entomologist.