By KURT WILLIAMS

Capital News Service

LANSING — Lake Huron is now the clearest Great Lake, dethroning Superior from the top spot while shedding new light on shipwrecks in Thunder Bay.

Lake Huron wasn’t always so clear.

In the past, untold numbers of microscopic plants and animals – phytoplankton and zooplankton – clouded the lake, especially in summer.

Now the numbers of these tiny life forms have plummeted, making the lake clearer, said Gary Fahnenstiel, a research scientist at Michigan Technological University.

Fahnenstiel and his colleagues made this startling discovery using sophisticated satellite imaging of the upper Great Lakes between 1998 and 2012.

The spread of invasive quagga mussels, which filter plankton, and reduced levels of phosphorus that feeds them, contributed to a dramatic increase in clarity, he said.

That change in the second-largest Great Lake has benefited the underwater experience for visitors to Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

The sanctuary encompasses 4,300 square miles of Lake Huron off the coast of Alpena. Nearly 100 shipwrecks have been identified there, but there may be as many as 200 in its waters, said Stephanie Gandulla, the sanctuary’s maritime archaeologist.

The wrecks and clear water make Thunder Bay popular with scuba divers from around the world, Gandulla said.

She’s been at Thunder Bay for 10 years and said she’s never known its waters not to be so clear.

But Steve Kroll has.

The 69-year-old retired math teacher from Alpena has been scuba diving in Lake Huron for 54 years. He remembers what it was like to dive the wrecks before the mussels’ invasion, when underwater visibility was often poor.

“When I first started diving shipwrecks, we had what we called braille dives,” Kroll said.

“A good day of diving was when you could see 5 to 7 feet,” he said. “Now if you have 5 to 7 feet of visibility, there are probably some people thinking we shouldn’t be diving,” Kroll said.

Dive conditions now couldn’t be more different, Kroll said.

When diving on 110-foot-deep wrecks in Thunder Bay, the visibility is so good that “it’s like all the water came out of the lake,” he said. Visibility at those depths is limited only by the amount of light reaching the lake bottom, not by the clarity of the water.

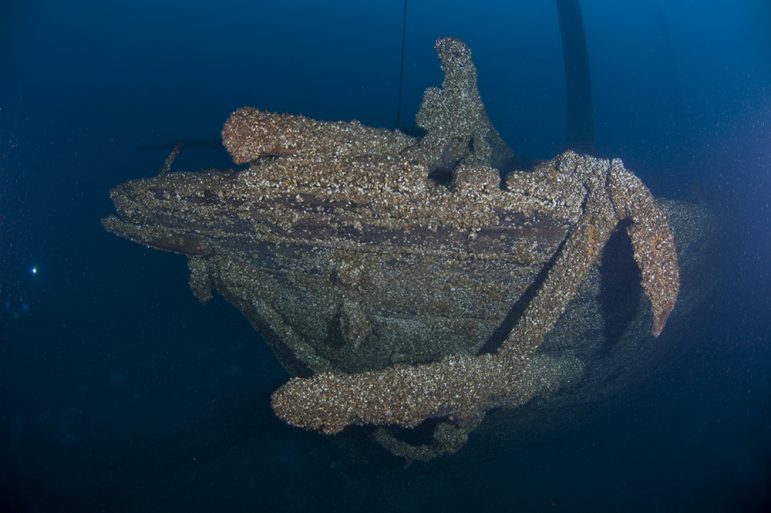

While the mussels contribute to increased visibility, divers encounter wrecks covered in them, making it difficult to appreciate their intricate details, he said.

Kroll refers to such wrecks as “chia pets” because of their resemblance to the popular figurines sporting sprouted spikes.

In the old days, he and his dive partners could admire the wood and sculpture and shape of the vessel, he said. They saw details of the ship’s construction and knew whether it was pinned or spiked.

Those details now are mostly lost under a coating of mussels.

For Gandulla, the mussels make cataloguing details about newly discovered wrecks difficult.

Her team uses photogrammetry, a technique that relies on obtaining detailed photographs of the wrecks, to identify them. The mussel layer obscures important details necessary to do the work accurately, she said.

How can something so seemingly simple as mussels play a role in clearing a lake the size of Lake Huron?

While we don’t know how many quagga mussels there are in Lake Huron, we do know something about their capacity to filter water.

Ashley Elgin, who has studied quagga mussels for years at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Muskegon, is astounded by the filtering capabilities of these humble animals no longer than the width of your thumb.

“If I were to give you a conservative estimate, one mussel can filter one liter of water per day,” said Elgin, a benthic ecologist — one who studies organisms that live on the bottom of water bodies. There are some reports of individual quagga mussels filtering up to 7 liters of water per day.

Knowing their capability, if you know the volume of Lake Huron and how quickly they cleared the lake, you can do a back-of-the-envelope calculation to figure out the population of mussels.

It’s a large number, she said.

Gandulla said the coating of mussels doesn’t appear to have damaged the wrecks yet, and the biggest risk to the wrecks may be from the weight of the mussels.

Elgin said the mussels produce byssal threads, fine hair-like structures, along with a sticky glue-like substance, to firmly attach to the vessels. If divers pull mussels off, they may pull wood off with them.

Now that clear water is the new normal for Thunder Bay and northern Lake Huron, people are used to it, and for those making a living around the sanctuary, clear waters lure visitors.

It’s a selling point to potential visitors, Gandulla said.

Kroll said he’s happy with dive conditions and knows what would happen if Thunder Bay went back to the way it used to be: “We’d lose a lot of divers. I don’t think we’ll ever go back. We’ve done what we’ve done.”

Kurt Williams writes for Great Lakes Echo.