By NICK KIPPER

Capital News Service

LANSING — Michigan lawmakers are considering moving 17-year-olds from the adult to juvenile court system.

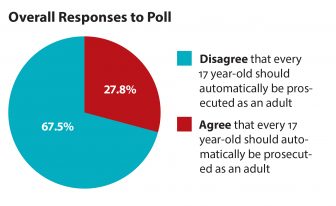

Voters Overwhelmingly Support Raise the Age Legislation. Source: Michigan Catholic Conference

Supporters say the change is needed to protect juvenile offenders from violence and reduce the likelihood that they will reoffend. Michigan is one of only four states that treats 17-year-old offenders as adults.

“Adult correctional facilities are not designed for children,” said Jason Smith, the director of youth justice policy at the Michigan Council on Crime and Delinquency. “Research shows that young people under the age of 18 are highly susceptible to being victims of violence at the hands of older inmates and staff, sexually and physically.”

The largest roadblock facing the 19-bill package is the projected additional cost to county governments and the juvenile court system.

“There’s no funding attached to any of these policies,” said Meghann Keit, a governmental affairs associate at the Michigan Association of Counties. “In order to really serve the additional population we need more resources because the juvenile court system is much more costly than the adult. There’s a lot more treatment and rehabilitation that goes into it.”

Other groups opposing the move are the Michigan Probate Judges Association, Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan and the Michigan Association for Family Court Administration.

The Raise the Age legislative package would cost the state and county governments a combined $27 million to $61 million annually, according to the Legislative Council Criminal Justice Policy Commission.

“Right now a lot of northern counties and rural counties are having difficulty finding detention bed space for their 14-, 15- and 16-year-olds that are already in the system,” Keit said. “The Legislature definitely needs to address the capacity issue before we move forward with these bills.”

Groups that oppose the bills support the concept of bringing 17-year-olds into the juvenile courts, but can’t support them until adequate funding is presented, Keit said.

County governments would be hit hardest, as they initially assess a child when they come into the juvenile court system. A judge determines the treatment needs and then the county provides that service. The county sends the cost of the service to the state and is reimbursed for half, Keit said.

There are 21 county or court-operated juvenile detention facilities across the state.

Some local police officials agree that the change is needed to accommodate offenders who are not mature adults.

“They don’t have a lot of adult responsibility,” said Mackinac County Sheriff Scott Strait. “They don’t do a lot of things without parental consent except committing crimes.”

Federal law defines adulthood as 18 years old. But in Michigan, a 17-year-old is considered an adult in the eyes of the court.

“The capacity that the court has to handle juvenile cases might not be there,” Strait said. “That could put in limbo 17-year-olds newly put into the system.”

The Council on Crime and Delinquency is the leading the campaign with a “raise the age” slogan.

“We’re hoping that this legislation can be an opportunity for Michigan and its counties and juvenile courts to take the opportunity to look at where they can reform this system in other ways, just like every other state has when they’ve passed this kind of legislation,” Smith said.

A recent statewide poll by the Michigan Catholic Conference found that more than two-thirds of 600 likely voters said that a 17-year-old should not be automatically prosecuted as an adult.

“We support a two-year implementation date to give counties time to assess and the courts time to assess what their needs are and where the capacity gaps are for staff and facilities,” Smith said.

A similar package passed the House but stalled in the Senate in the last legislative session. The package got a recent hearing in the House Law and Justice Committee. Supporters say they hope that the committee will put the bills to a vote after the fall election, Smith said.

“Compared to previous years, all the parties involved — the county stakeholders, state government, the governor’s office, Department of Health and Human Services — have been much more collaborative and really solution-focused in trying to figure out how to overcome some of the barriers we face, which aren’t much different than other states,” Smith said.