By KURT WILLIAMS

Capital News Service

LANSING — Three men pull a fat-tired wagon filled with scientific equipment through the sand of Muskegon’s Pere Marquette beach. Dressed in layers against the late spring cold, their camo-print chest waders lend a rocking character to their gait not typical of beachgoers.

“It’s one of the most fun things we get to do in our jobs,” said Steve Pothoven, a fishery biologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory in Muskegon.

Kurt Williams

NOAA scientists prepare to seine net Lake Michigan for juvenile lake whitefishPothoven and fellow researchers Jeff Elliott and Aaron Dunnuck work beaches along Lake Michigan in May and June, studying how well young lake whitefish grow to be adults.

Lake whitefish in Lake Michigan and Lake Huron have a recruitment problem.

Since the early 2000s, fewer young whitefish have been making it to adulthood. Fewer adults mean fewer fish for commercial fishers to catch.

“We just don’t know a whole lot about these fish and what supports them early in their life,” said Pothoven.

They study the problem at familiar and popular beaches – places like Pere Marquette and Grand Haven State Park.

They get to work.

Dunnuck hits the water. Walking straight into the lake, he drags 150 feet of seine net weighted on the bottom, the water rising to his chest. Turning left, he walks parallel to shore, the net unfurling, forming a crescent as he returns to shore. He and Elliot pull in the net, gathering up any fish in its path.

On shore they open the net to assess their haul.

On this day it’s scant.

A few small silvery fish – what most people would call “minnows” – lay in the net.

They rapidly identify and count all the fish, keeping the whitefish and tossing the rest back.

Dunnuck heads back into the water with a small net on a pole with a small jar on the end to sweep through the water. He’s collecting zooplankton – baby lake whitefish food – to see what’s out there for them to eat.

Back at the NOAA lab, Elliott looks at the zooplankton under a microscope, identifying the tiny animals based on differences in their otherworldly bodies. He’ll open the stomachs of the young whitefish to compare what they’re eating with what’s living in the water.

Understanding the decline of lake whitefish recruitment is important as fishery managers and regulators approach the deadline to update a 2000 consent decree regulating recreational and commercial fishing in lakes Huron and Michigan.

Prized for its mild flavor, finding whitefish on the menu of local restaurants is an important part of the “Up North” experience for summer tourists.

Lake whitefish compose 95% of sales of commercially caught fish in Michigan, with a dockside value of just over $4 million, Sea Grant, Michigan reported in 2020.

Kurt Williams

Juvenile lake whitefishFor members of tribal communities, lake whitefish are much more than a source of income. The fish have been integral to their diet and culture for thousands of years.

Understanding why young lake whitefish struggle across much of the Great Lakes is a major focus of fisheries research by the state and tribes.

“You have to remember, 99.9% of all fish eggs laid, die,” said Mark Ebener, a fishery biologist who worked 37 years for two inter-tribal Great Lakes organizations. He is the lead author of a 2021 review addressing declining recruitment in lake whitefish published by the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

Most of the evidence for poor lake whitefish recruitment points to one culprit: invasive mussels.

The premise is that quagga mussels have fundamentally changed how energy flows through the system, dramatically reducing zooplankton in nearshore waters, Ebener said.

Zooplankton are the primary food source for baby lake whitefish.

The timing of the mussels’ arrival and the drop in lake whitefish recruitment is likely more than mere coincidence.

“Yeah, certainly, we think that’s one of the primary causes of the decline in whitefish recruitment – the lack of zooplankton,” Ebener said.

With so many people fond of a fish struggling so mightily to hold its own, a key question for negotiators is how many can be harvested each year if fewer are reaching adulthood?

It takes more time now for lake whitefish to become large enough to be caught commercially and old enough to reproduce the next generation.

“It used to just be two to three years and they’d be in the fishery, probably reproducing,” said NOAA’s Pothoven.

Because of the mussel’s impact on the base of the food web, now it takes at least five years, and perhaps up to seven or more, he said.

“They don’t grow like they used to.”

Pothoven and a team are trying to understand the early life history of lake whitefish.

The team is led by Kevin Donner, the Great Lakes Fisheries program manager of the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians in Harbor Springs,.

“For us, when we started this in 2013, whitefish were already in decline, but we didn’t know how much,” Donner said.

Predicting the future is always dicey.

Kurt Williams

Jeff Elliott and Aaron Dunnuck collect juvenile lake whitefish from a seine netA major concern is that by the time they collect information on fish big enough to be commercially caught, six or seven years may have passed without anyone knowing there might be problems that began while the fish were babies. Nobody was looking.

“So, if something bad happens, = for example today, let’s say no whitefish are born for whatever reason, we are going to continue along on our merry little way for seven years before anyone has enough data to say, ‘Oh God, something’s wrong.’” Donner said.

It could also go the other way.

If the group’s work bears fruit, it might calm nerves and predict better how many are available for commercial harvest years in advance.

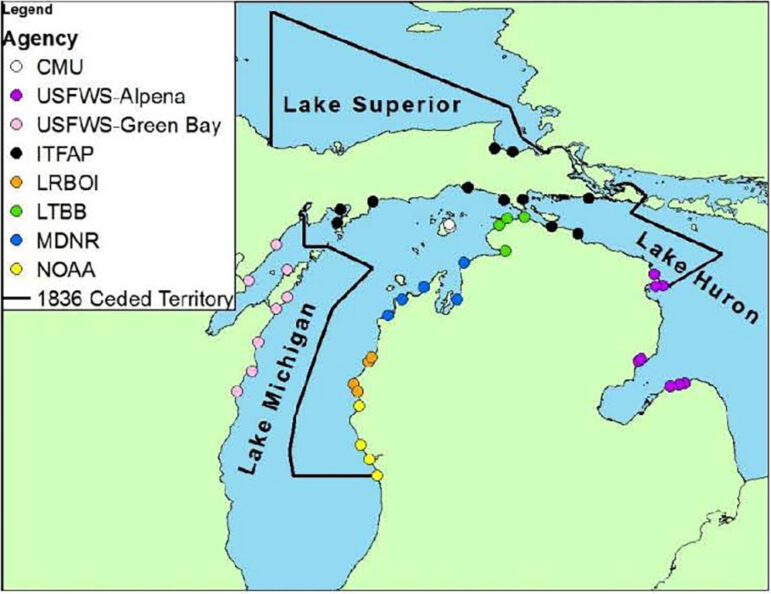

Since 2013, the survey team has sampled beaches in the spring, mostly in the northern Lower Peninsula.

Lake whitefish spawn in autumn, favoring protective rocky nearshore areas. When eggs hatch in the spring, the larval whitefish survive off a yolk sac, a pouch coming off their bellies filled with fats and other goodies, until they’ve grown enough to hunt on their own.

When this happens, they venture into open waters, many choosing the seemingly barren environment found on sandy beaches favored by people.

“Most people wouldn’t even know that larval whitefish exist right around their ankles just before they’re comfortable swimming in the lake,” Donner said.

There are places in the Great Lakes where baby lake whitefish do much better.

Ebener said, “Lower Green Bay is still good, Saginaw Bay is good, the north channel of Lake Huron is good, Lake Superior is still good. The problems are in the open waters of the main basin in Lake Michigan, Lake Huron and Lake Ontario.”

In areas where lake whitefish do best, mussels don’t have the stranglehold they do in the open waters of lakes Michigan and Huron.

It’s always been risky to be a baby lake whitefish. Improving their odds for survival even a little bit can pay off significantly, Ebener said.

If 99.995% of fish eggs don’t survive, even a miniscule bump in baby fish surviving can be very important to the species, he said.

“It’s a numbers game.”

Kevin Donner

Map showing Michigan sampling sites in the 1836 Treaty waters where juvenile lake whitefish have been collectedKurt Williams writes for Great Lakes Echo.