Michigan public schools have been underfunded for two decades, but the results of the 2022 gubernatorial election could change that, education advocates say.

During her first term, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer made K-12 funding a priority by allocating $17.1 billion in COVID relief money to public schools, said David Crim, communication consultant for the Michigan Education Association, which on Dec. 3, sent out a press release endorsing Whitmer, Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson and Attorney General Dana Nessel for reelection.

Crim said the 2021-2022 school funding budget that passed over the summer was “historic and transformational.”

Creating a brighter future for education

K-12 funding took a big hit in 2011 when the newly elected Gov. Rick Snyder diverted money from public education to pay for corporate tax cuts, Crim said.

“You can’t say you support public education and cut funding,” Crim said. “You can’t say you support public education and continue undercutting teachers. Those things don’t go together.”

The day of the gubernatorial election is the most important day for education funding and policy, said David Hecker, president of American Federation of Teachers Michigan. He said he encourages voters to figure out where candidates stand on K-12 funding before casting their votes.

“Everybody running for office says they support public education, but voters have to look into what candidates actually propose to do,” he said.

According to data from the state of Michigan, per-pupil funding in a majority of school districts has increased from $8,111 during the 2019-2020 school year to $8,700 for the 2021-2022 school year.

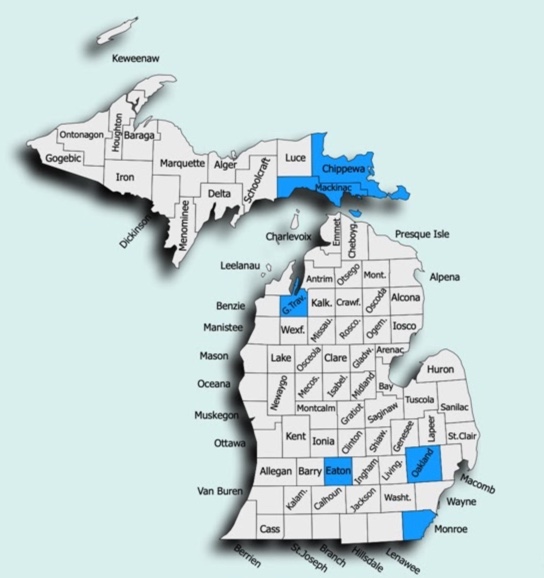

Bloomfield Hills Public Schools in Oakland County received $12,517 per-pupil for the 2021-2022 school year while Saugatuck Public Schools in Allegan County only received $8,686 per-pupil.

“A $17.1 billion funding increase to K-12 education is wonderful,” Crim said. “It will not make up for the two decades of underfunding of public education in Michigan, but it’s a good start.”

Focusing on the students

David Lyons, an English teacher at Kenowa Hills High School, said the district used some of the extra funding to hire more staff.

Lyons said the district hired a school nurse for each building, a diversity equity and inclusion director and a transition coordinator for students graduating.

“When the state looks at funding needs they base it on standardized test scores. My hope is that they will shift the focus to brain health issues,” Lyons said. “We want to be able to work with these students so we don’t have incidents like we did in Oxford.”

Lyons said he worries how the district will continue to support its new hires once COVID relief funds run out. He said he is paying attention to what the candidates for governor propose.

“I’m listening for a focus on the social and emotional parts of students,” Lyons said. “I’m also looking for using funds available to put money back in the classrooms.”

K-12 funding then and now

Crim said the continuation of funding increases under Whitmer depends on who is elected to public office.

“Our education system is in a better place now than before, especially with what Governor Whitmer has done,” Crim said. “Our goal going into this election is to make sure we elect and reelect people that support public schools and public school employees.”

Over the past 20 years, K-12 funding has become more reliant on state funding than local taxes, Crim said. However, some districts in high-income areas still have more per-pupil funding because of the lingering effect of local tax revenue.

“Part of the problem is that for-profit charter schools now get a billion dollars a year out of our K-12 budget,” he said. “A lot of that money’s been diverted from neighborhood public schools.”

Lack of education funding was not always an issue in Michigan. Crim said Michigan ranked highest among Great Lakes states in education funding and student achievement 20 years ago.

However, data from 2020 shows Michigan ranking last in the region in both categories, he said.

Other funding sources

Many school districts get supplemental funding from foundations that alumni and community members donate to, said Amy Stuursma, executive director of the East Grand Rapids School Foundation.

“The funds raised go toward enhancing teaching and learning in our district beyond what the district can do with general funds,” she said. “That comes in the form of enhancement grants to classrooms or programs that we fund.”

Stuursma said the funding from the foundation is used for a combination of meeting the basic needs of the district and enhancements.

“When we were founded over 30 years ago, we were meant to be enhancement only,” she said. “As times have changed and funding has been reduced, we’ve had to fund some of the more basic programs in the district.”

The foundation has been essential for preserving programs that would have been cut when funding was reduced, Stuursma said.

“We hope to get back to focusing more on enhancing our district instead of patching up where funding has been reduced,” Stuursma said.

Over the years, the foundation has paid for teacher training, student scholarships, science data collection devices, revamping classroom libraries and bringing special guests into the schools, she said.

Kristia Postema

A dusting of snow covers the East Grand Rapids High School football stadium. Money raised by the East Grand Rapids School Foundation has helped pay for stadium upkeep and renovations over the years. Photo by Kristia Postema.Inequitable funding

Not all school districts have access to the same community resources as East Grand Rapids, so funding is still an issue for them, Crim said.

Despite only a few miles separating the districts of East Grand Rapids Public Schools and Grand Rapids Public Schools, there are major funding disparities between the two. For the 2019-2020 school year, EGRPS received about $200 more than GRPS in per-pupil funding.

Mary Bouwense, the full-time release president of the Grand Rapids Education Association, said GRPS needs additional funding to meet infrastructure needs.

“We have quite a range of buildings, some fairly new ones and some from the turn of the 19th century,” she said. “It’s disrespectful for the kids to have to go to a school that’s crumbling and has broken sidewalks and leaky ceilings.”

Increasing funding equity

Hecker, of American Federation of Teachers Michigan, said the legislation passed to increase K-12 funding was bipartisan, but Whitmer played a major role.

“We applaud Governor Whitmer, her leadership and the most recent K-12 budget,” he said. “It really helped some districts that were underfunded.”

Hecker said the budget helped equalize funding but it did not create equitable funding. The School Finance Research Collaborative determines equitable funding by taking into account differences in resources and needs between school districts.

“Most schools in low-income communities need more funding for their students to succeed than school districts with more middle and upper-class families,” he said.

Public schools need at least $4 billion more to reach equitable funding, Hecker said.

Extra pressure on teachers

Sandy Keeney, an early childhood special education teacher at Lowell Public Schools, said she has seen a dramatic decrease in education funding throughout her 36 years teaching.

Keeney said other districts near Lowell are more adequately funded.

“I would like to see education funding more evenly distributed, Forest Hills is adjacent to us and they receive more per-pupil funding” she said.

Keeney said funding goes down every year, and she has to buy supplies for her classroom with her own money.

The teacher shortage

The lack of funding is directly responsible for problems such as the teacher shortage, Crim said.

“Teachers have been underpaid, overworked and disrespected for years,” he said. “After the 2020-2021 school year we saw a 40% increase in teacher retirements.”

New teachers aren’t staying in the field either. Over the past decade one in five new teachers left the profession in their first five years, Crim said.

“I have been at MEA for 30 years. I’ve never seen lower morale, or more frustration,” Crim said. “There are many legislators who have no interest in paying teachers higher wages and they don’t believe the teacher shortage is real.”

“If we continue to have this dire shortage of educators, politicians are going to have to decide if they want to fund schools, or if they want to continue to see the destruction of public schools in Michigan,” Crim said.