The digital divide among students with different at-home resources has existed for years, but the pandemic brings the gap to the state’s attention. Full-time remote learning has revealed disparities beyond devices and internet access, including varied transportation, tech support, and parental support available to students at home.

Access to devices is just the start

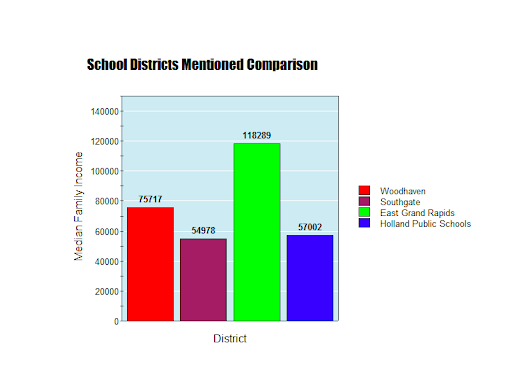

Cathy Mikesell, a 4th grade teacher in the Woodhaven school district, said students in Downriver districts are generally equipped with devices and Wi-Fi.

“Everybody in my class, and I think in my school, has the internet,” she said. “If they didn’t have a computer, the school gave them a Chromebook. We’re really good with that, and that’s not the case everywhere, I’m sure.”

Rachel Lott, a speech therapist from Southgate, also said her district had plenty of devices to spare.

“Once we decided to go remote, [the district] took the time to assess,” she said. “We have to have a fair and equal playing field as much as possible. We can’t control how engaged the parents are, we can’t control how focused the child is, but we can control that every single child has a laptop.”

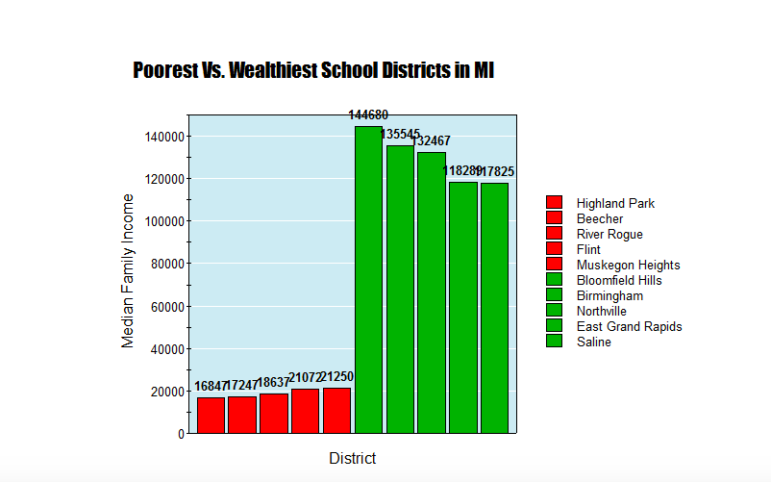

In East Grand Rapids, the fourth wealthiest school district in Michigan, according to MLive, elementary students receive similar treatment.

“They did a survey. They wanted to know if you had Wi-Fi and your own laptop, and if not, they provided one for you.” said Gretchen Deegan, parent of a 3rd and 5th grader.

Internet access is spotty

Lott didn’t see many students lacking internet access, either. She was thankful, as she has worked in districts with much higher rates of poverty.

“I saw a lot of companies — and I know the district would, if it came to it — helping families pay for their Wi-Fi it’s taken for granted that some families cannot afford monthly internet.”

Deegan is a prime example.

“I don’t know what they would’ve done if you didn’t have the internet, though. But we did.”

Wendy Nowak, director of technology services in Southgate, said the district has moderate need relative to other districts.

“We purchased less than 50 hot spots. I really had no idea, at the beginning of this, how many would be requested,” she said. “What we’ve heard anecdotally is that they’ve lost their job, or they can’t afford to pay for the internet at home.”

Nowak said rural areas have more holes in internet connectivity.

“Some districts were putting [internet] access points on buses and driving buses down a street. That was for more rural areas,” she said. “That was a big divide.”

Mike Potts, superintendent of Waldron Area Schools, near the Ohio border, said his schools struggled with internet access when they originally moved to online learning.

“Students have always been underserved when it comes to internet access,” he said. “However, with the [Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief] funds that have been dispersed to schools, we now are able to provide all the students who need them with a hotspot to utilize for their schoolwork.”

Although this is a start, he believes more could be done. “While this is a great improvement, it is not comprehensive for our kids.”

Even for remote learning, transportation is vital

Woodhaven has relatively solid access to devices and Wi-Fi, but Mikesell said those are not the only resources necessary for remote learning. Younger students need access to hands-on supplies and that can mean a car to pick them up.

“For elementary, we do a material pickup. Every couple weeks, the parents will come to the school and we have bags of things ready for them,” she said. “But then there’s people that don’t have a car. So, I deliver it to their houses.”

Mikesell delivers supplies by choice. If not for her extra effort, there would be a major divide in her classroom.

“I’m not trying to say everybody wouldn’t do that but … I do it because I feel for the kids,” she said.

Nowak said transportation drives a divide between students in Southgate, too.

“You can put a ticket in to us and we can help you, but if you can’t come up here to get it repaired there’s nothing we can do,” she said. “The kids had to rely on some kind of motor transportation to come up here and get a new Chromebook. Sometimes three or four days would go by, and they’ve lost those four days of instruction.”

Like Mikesell and others, Nowak took the matter into her own hands to help students in need of resources.

“I’ve delivered two Chromebooks personally because the parents can’t,” she said. “I know principals have, I know teachers have … it’s amazing what our staff has done to help kids and lessen that divide.”

Technology support is essential

Nowak said access to tech support varies among students and causes a major divide.

“We had 400-500 [tech support] tickets, from just students. There were also hundreds of staff tickets,” she said. “We’ve never had this many tickets. We couldn’t even keep up.”

Candace Duane, a social worker in Southgate, said the quality of students’ devices is another aspect of the divide. Communication with students is less effective when their devices malfunction often.

“The Chromebooks crash,” she said. “Some kids’ mom or dad outfitted them with a nice little laptop or desktop so they never had Wi-Fi problems or connection issues. And then you’ve got kids on the Chromebooks that didn’t always function that well. The digital divide was big time.”

Educators are not alone in feeling the frustrations of uneven technology. Duane said connectivity issues take a heavy toll on students’ stamina.

“You’ve got to have solid technology, or it makes everything about all of this so much harder,” she said. “It’s almost the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Like, ‘I already miss being in person, I’m already struggling online, this is already sucking the life out of me, and now my Chromebook crashed for the fifth time today.’”

When school-provided devices became an obstacle to learning, Duane said she needed to purchase better equipment for her own child.

“I have a fifth-grade daughter and we kept her home the first trimester,” she said. “My husband and I decided it’s not really in the budget, but we bought her a desktop. We cannot struggle with technology. It’s hard enough for her to hear the kids walking by going to the bus stop.”

Parental support drives access to all resources

Nowak said most aspects of the divide–devices, internet connectivity, transportation, and technology support–depend on parental support.

“With the divide, it really comes down to parental support. The kids that have it do better,” she said. “There are kids who are sitting at home on their own, without parents to guide them or follow up on their education, or make sure they are logging in on time, or logging in at all.”

Nowak said the technology department often deals with parents that do not email or know how to submit a tech support ticket.

“We’ve had a lot of grandparents that we’ve talked to this year say, ‘Their Chromebooks aren’t working or I don’t know what their login is’,” she said.

Nowak said the divide boils down to missed instructional time.

“When you wait three days for a support ticket, that’s three days of instruction lost,” she said. “We felt that pressure deeply. I felt that every time I saw someone not being able to be helped today, I thought, ‘That child missed a whole day of instruction because they’re waiting for us.’ And that’s just horrible.”

‘The greatest resource is a loving parent’

However, some say that the love and dedication of a parent can help children overcome even the hardest circumstances.

“Almost every one of the cases of the kids that I’ve worked with, one thing you can never underestimate is the love of the family,” said Mary Siebers, Kids Hope mentor for students in underfunded schools in west Michigan. “Even though there are very few, if any, resources the greatest resource is a loving parent.”

To Siebers, just one loving parent can make a world of difference for a child’s future.

“When I was a volunteer probation officer for the Kent County juvenile court, every kid who eventually broke out of the system was one who had a loving parent. Maybe not two loving parents, but one loving parent.”

She has seen this apply to the students she mentors.

“That was the strongest resource they could have, even if material resources were few and far between.”