By BRANDON CHEW AND TAYLOR HAELTERMAN

Capital News Service

LANSING – Michigan requires political candidates to report donations and expenditures of their campaigns, but it can be challenging to track them.

And that can include a lot of money, even in county-level races for posts that many voters rarely think about.

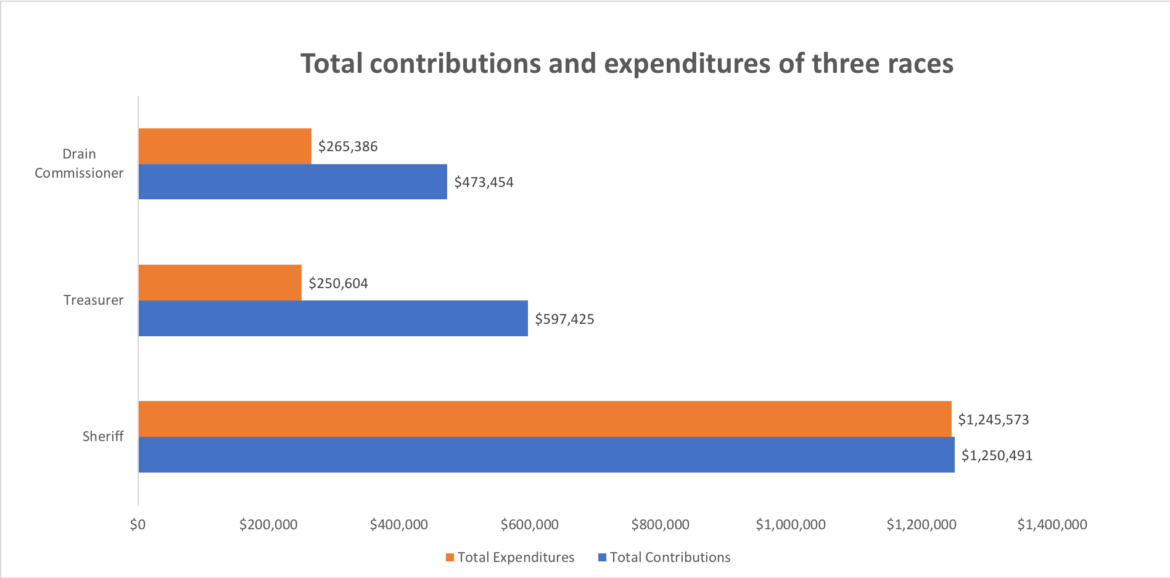

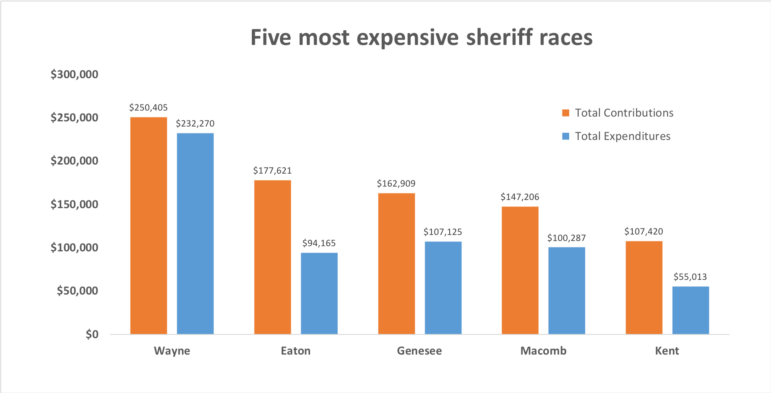

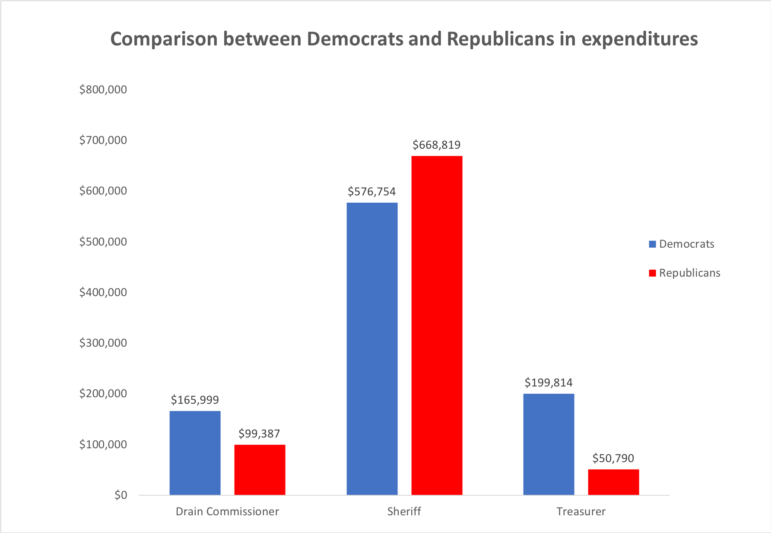

In a study of three county level races encompassing 56 Michigan counties, Michigan State University journalism students discovered that between Jan. 1, 2018 and Sept. 23, 2020 candidates for sheriff raised more than $1.25 million to fund their races.

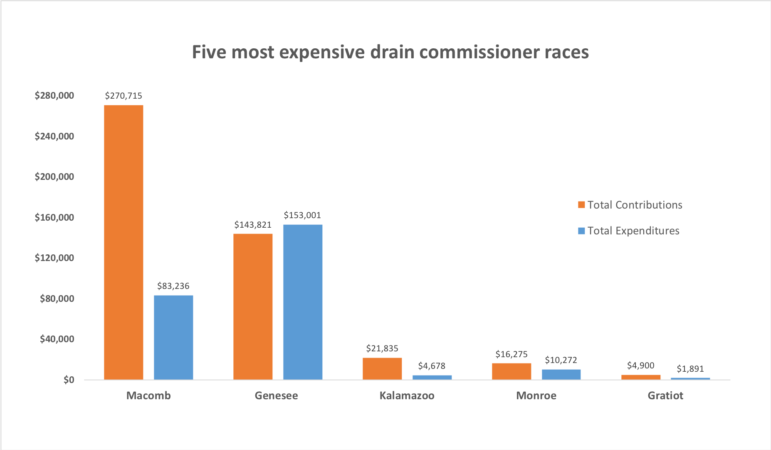

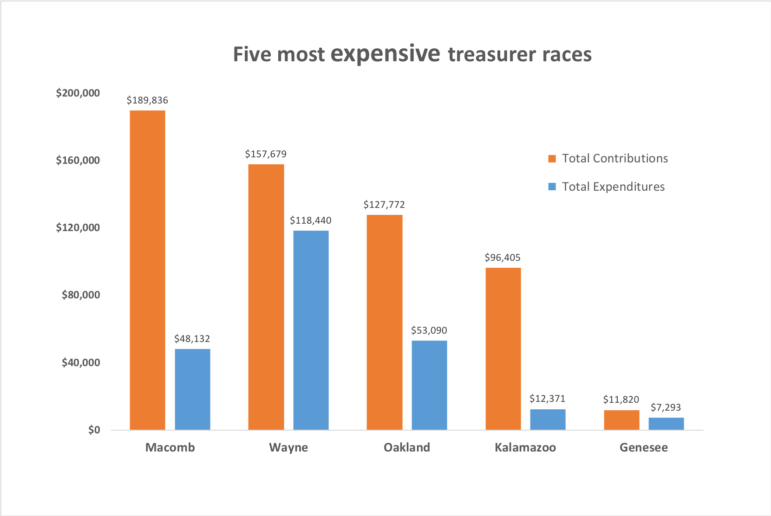

Candidates for treasurer raised nearly $600,000 during the same period. Even candidates for drain commissioner raised nearly a half-million dollars.

And it is likely more. The reporting period studied ends at a post primary deadline that does not include the time immediately before the general election when fundraising and spending intensifies.

Among the barriers to obtaining records the study found:

- Few counties put them online

- Reports come in formats difficult to analyze

- Clerks are slow to respond, especially during the hectic election season

- Fees are sometimes required to obtain records

- A decline in local news reporters means fewer people track local contributions.

“Michigan has some of the weakest campaign finance rules and regulations in the country,” said Ingham County Clerk Barb Byrum, who like all other county clerks is responsible for reviewing the financial records of campaigns for county office.

The system is unsuccessful at keeping those running for government positions accountable for their spending habits, she said.

Even when a complaint is referred to law enforcement there is often nothing done, Byrum said. How often these complaints are referred to law enforcement or other state officials for enforcement is unclear. Michigan has no centralized system for tracking county level complaints.

“The system’s not great, especially in Michigan, but it’s what we have and I don’t see the Legislature making our campaign finance act more robust,”Byrum said.

Simon Schuster, the executive director of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network, agrees.

“If the goal of the Michigan Campaign Finance Act, and our campaign finance system, is to track all of the money that is used in campaigns and determine who is funding those efforts, then no, it is not effective,” said Schuster, whose nonpartisan nonprofit organization educates the public on money in politics. “But in narrow terms it does succeed in some aspects, such as limiting the amount of contributions an individual’s campaign can receive.” Those limits vary by county population.

A key problem is that the decline of local media means fewer reporters have time to review campaign finance records, Schuster said. That duty then falls upon the local residents who may not know the technical aspects of searching for these records.

These problems make it harder to collect data and explain it to the general public.

The audit found that records were available online for only 11 of Michigan’s 83 counties, according to the Campaign Finance US website. For the other counties, clerk’s offices were contacted directly to request the information.

Campaign finance records were collected from 56 counties. More than a quarter of the 44 people involved in requesting them reported difficulty collecting the records.

In some cases a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request needed to be filed. These are formal requests submitted to government agencies to gain access to records as it is a public right.

FOIA was sometimes an effective tool for gaining the attention of even time-strapped clerks getting ready for the election.

MSU student Matt Dwyer asked the Ontonagon County clerk several times for the documents. He didn’t get a response until he submitted a FOIA request.

“They kind of blew me off, but then as soon as I sent the FOIA for Ontonagon I got an answer within like 30 minutes,” Dwyer said.

Three students received fee requests of under $20. Livingston County officials requested $80 for the records, said student McKoy Scribner who did not pay it or receive the documents.

“I emailed (the clerk) Oct. 13, about the detailed pricing,” Scribner said. “It was $2 a page, but I really haven’t heard anything about what to do, or anything since.”

Livingston County Clerk Elizabeth Hundley, said she has to search for the records by hand. She doesn’t have the funding for an online software to do it electronically which is why there is a fee.

“Depending on the number of records you’re requesting, if putting together that FOIA takes less than 15 minutes, there’s no cost for that FOIA request,” said Hundley.

Hundley recommended those looking for county-wide campaign finance records submit a separate FOIA request for each candidate to keep search time short and avoid the fee.

Byrum was shocked that students needed to file FOIA requests or pay fees.

In her opinion, the only reason fees would be charged is if the individual requesting the documents refused to accept them electronically and the clerk needed to print the information, Byrum said.

“Under no circumstance would I require a FOIA to be filed for information such as campaign finance that should, quite frankly, be publicly available without having to file a FOIA or jump through hoops in order to obtain,” Byrum said.

Schuster was surprised that a clerk would offer a workaround to avoid fees in the system instead of changing the document request system.

“The clerks are often responsible for determining these systems, so if a clerk is suggesting a workaround to avoid filing fees for the system that she established I don’t know if that’s particularly sensible,” Schuster said.

But most requesters had an easy time.

“Overall it was pretty positive I’d say,” said MSU student Tyler Castillo. “I really didn’t have any struggle at all getting a hold of them or getting the files. There was no fee. I didn’t have to fill out a FOIA or anything like that.”

The Michigan campaign finance system will improve only if voters demand it, Byrum said

“Lobby your legislators,” she said. “The problem is the system that you’re lobbying for, a more robust system, they too will have to comply with and they don’t want to.”

Solutions will only come from a grassroots amendment to the campaign finance laws demanded by voters with a ballot initiative, Byrum said.

This story is part of a series that looked at finance reports filed for Michigan county treasurer, drain commissioner and sheriff campaigns. Michigan State University students from four classes examined reports filed between Jan. 1 2018 and the post primary filing deadline of Sept. 23, 2020.

Stories in this series: