LANSING — While the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops garners much attention as the leading voice of the church in the U.S., the Leadership Council of Women Religious — which represents 35,000 Catholic sisters — is also working on a number of social justice issues.

The council holds political power, as sisters take part in legal advocacy and activism which can influence lay Catholics across the country.

The council, which is headquartered in Silver Spring, Maryland, is composed of leadership from 300 congregations. As such, it represents 80% of women religious, a term that refers to Catholic sisters, across the country. In the past 40 years, the Council has become much more active both on issues in the institutional Church and in American society.

In 1979, council President Theresa Kane, Religious Sisters of Mercy, called on Pope John Paul II to consider women’s ordination to the priesthood in front of a crowd of 5,000 sisters. In more recent years, the council was subjected to a seven-year doctrinal investigation. That ended in 2015. Just last year, sisters associated with the council were arrested in New Jersey and Washington, D.C., at protests focused on family separation and the treatment of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Council Director of Social Mission Ann Scholz, a member of the School Sisters of Notre Dame, helps member congregations get informed and work on issues the council has determined to be of importance.

“The Gospel calls on us to do a number of things, like welcoming the stranger,” Scholz said. “So we have done a number of things socially and politically to advocate for and help immigrants, asylum-seekers and refugees.”

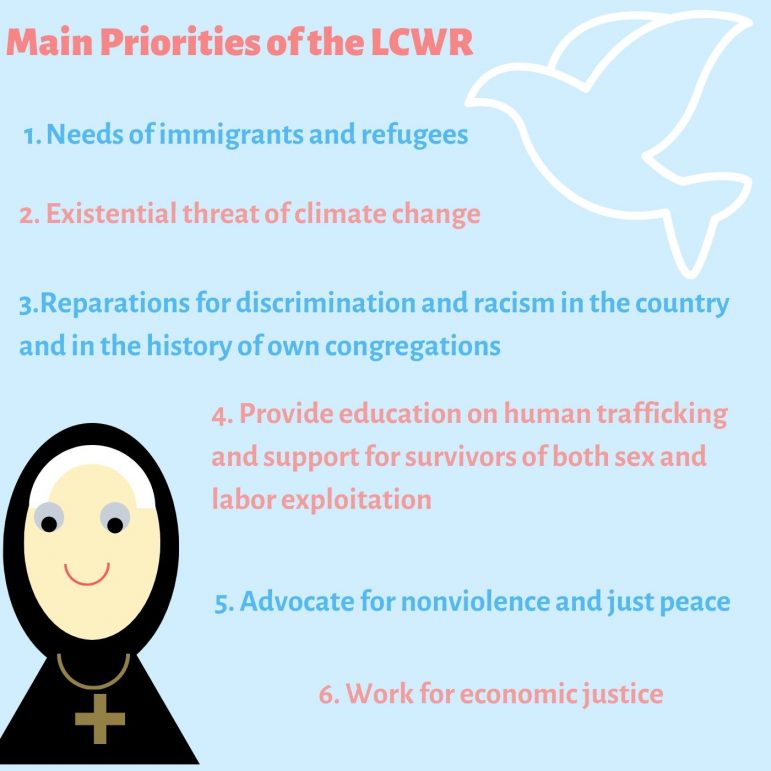

In addition to immigration, the council focuses on five other main issues: climate justice, nonviolence, human trafficking for both sex and labor, economic justice, and discrimination, including racism, within their own communities and in the nation.

Catholic social teaching and its importance to activism in the Church

“Catholic social teaching is grounded in the Gospel, and in Jesus’ life and his action,” Scholz said, “It is, in fact, a whole body of teaching. The Roman Catholic Church provides that revelation comes not just through the Gospel but also through the lived experience of the people of God.”

This body of teaching began during the global industrial revolution, when Pope Leo XIII wrote an encyclical on labor rights. The tradition of writing encyclicals — official documents written by the Pope — to develop Catholic social teaching has continued to the present issue such as climate justice. Although it’s been part of the church’s modern history, Scholz said Catholics shouldn’t be surprised if they’ve never heard of it.

“It’s the church’s best kept secret,” Scholz said. “They don’t preach about it on Sundays. Priests limit their teaching on Sundays to their preaching on the Gospels,” Scholz said. “Some guys may perhaps make reference to Catholic social teaching imbedded in that, but it’s not part of homiletics. And that, unfortunately, is the only adult education we get.”

East Lansing Catholic Network co-leader Al Weilbaecher also called Catholic social teaching the “church’s best kept secret.” Weilbaecher, a commissioned lay ecclesiastical minister in the Diocese of Lansing since 1977, helped form the area’s chapter of the Network Lobby, a faith-based organization started by Catholic sisters and made famous during the debate over the Affordable Care Act due to its Nuns on the Bus movement, which featured Catholic sisters and others who advocated on its behalf.

Women religious work to build “God’s loving community”

Weilbaecher became involved in Catholic social teaching through action under the guidance of Sister Liz Walters. She was very involved in social justice ministry and said women religious have pushed the Church forward, even at risk to themselves.

“It’s amazing what women religious have done in terms of Catholic social teaching,” Weilbaecher said. “And some have stepped on toes and gotten in trouble with the institutional church. They’ve really been pioneers for social justice. Network is comprised of mostly women religious from different orders at the top, and they’ve done some amazing work.”

Weilbaecher said, “it’s called, ‘The two feet of love in action.’ One foot is charitable works — meeting immediate needs. A lot of people like this because it’s really concrete and tangible. The other foot is social justice. This gets to the cause of questions like, ‘why do you have to have a food pantry or a homeless shelter?’ This foot tries to solve the systemic crises that create these problems. You need both.”

Weilbaecher and Scholz are aware that many Catholics and non-Catholics may never hear the term Catholic social teaching.

“We hope it plays a role even if they don’t put the same words on it,” Weilbaecher said. “We’re trying to bring the Gospel and the theology of human dignity to politics. In some ways, we’re still trying to put this in language that resonates with the decency and humanity of people, whether or not they’re religious. This obviously is faith-based for us, but we want to appeal to the basic human dignity and compassion that’s in everyone.”

Scholz says that while women religious have been active in promoting social justice, building what Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. called “God’s loving community” falls on every religious person.

“That’s our call as Catholics, Christians, and people of faith,” Scholz said. “You might even make a pretty good argument that it’s our obligation as citizens of the United States. I expect it from Catholic sisters as much as I do from any other person of faith in this country.”

Women religious come with diverse beliefs and strategies

Scholz acknowledges that stereotypes about women religious make some people not expect their activism at all.

“People have a stereotypical image of Catholic sisters that predates the civil rights movement, for sure,” Scholz said. “However if you look at the founders of religious congregations and those who brought it to the U.S., you’ll find many brave women who built hospitals and schools, and took covered wagons west. They were certainly among the most independent and adventurous women of 19th century America.”

Former Detroit Free Press reporter Patricia Montemurri, whose photo book, “The Immaculate Heart of Mary Sisters of Monroe,” will be released March 9, covered the Catholic Church for many years. While she wasn’t on the religion beat, she quickly showed that she understood the Metro Detroit Catholic community to the point that the paper sent her to Rome during the election of Pope Benedict XVI. Her interest in women religious ties back to the IHM sisters who taught her at St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic School in Dearborn, Michigan. She agreed with Scholz, and said Catholic sisters cannot be boxed into stereotypes.

“Part of the IHM direction in recent life is to explore their feminist origin,” Montemurri said. “When they were founded in 1845, and honestly for the next 125 years, nobody used the word feminism to describe what sisters were doing. But, the IHMs decided to really explore what their founders endured in educating legions of children in Michigan and other places in the country. They took huge chances. They ran colleges and schools, and that was all on the women.”

Montemurri agreed that not all sisters want to be activists.

“It speaks to the wide tent of the Catholic church and the wide viewpoints and perspectives,” Montemurri said. “In many ways it mirrors lay American politics. There’s a sister at every point of the spectrum. Even though the IHMs are seen as progressive and liberal, some individuals are not and are more conservative. There’s tension and discussions around some of that, as there are in every congregation.”

Non-partisan advocacy in a partisan system

Even with diverse viewpoints, Scholz said that women religious and the council press forward for social justice in a nonpartisan way.

“We don’t endorse candidates,” Scholz said. “We do not endorse any political parties. We absolutely do encourage participation in the political process.”

Weilbaecher expressed a similar sentiment, in that network is also nonpartisan, but struggles with that in the current political climate.

“Religion and politics make strange bedfellows,” Weilbaecher said. “What we try to be—and we’re not perfect—but we try not to make it partisan because neither party embraces the whole Catholic social teaching.”

To sum up what she thinks women religious think about when they vote, Scholz said that it would be similar to the beliefs they exhibit through their actions.

“The positions we take as an organization are really informed by Catholic social teaching, the Bible — specifically the Gospel, and the words of Pope Francis, who has been really clear that we have an obligation to preserve the dignity of our fellow humans and work for the common good. That’s — in broad strokes — what informs us.”

Debrah Miszak