By COLLEEN OTTE

Capital News Service

LANSING — It might seem counterintuitive, but when trying to examine the bottom of Lake Huron, researchers discovered it is helpful to take a look from space.

Satellite imagery offers a new tool for identifying nearshore habitats where lake trout spawn across broad areas of the Great Lakes, according to a recent study in the Journal of Great Lakes Research.

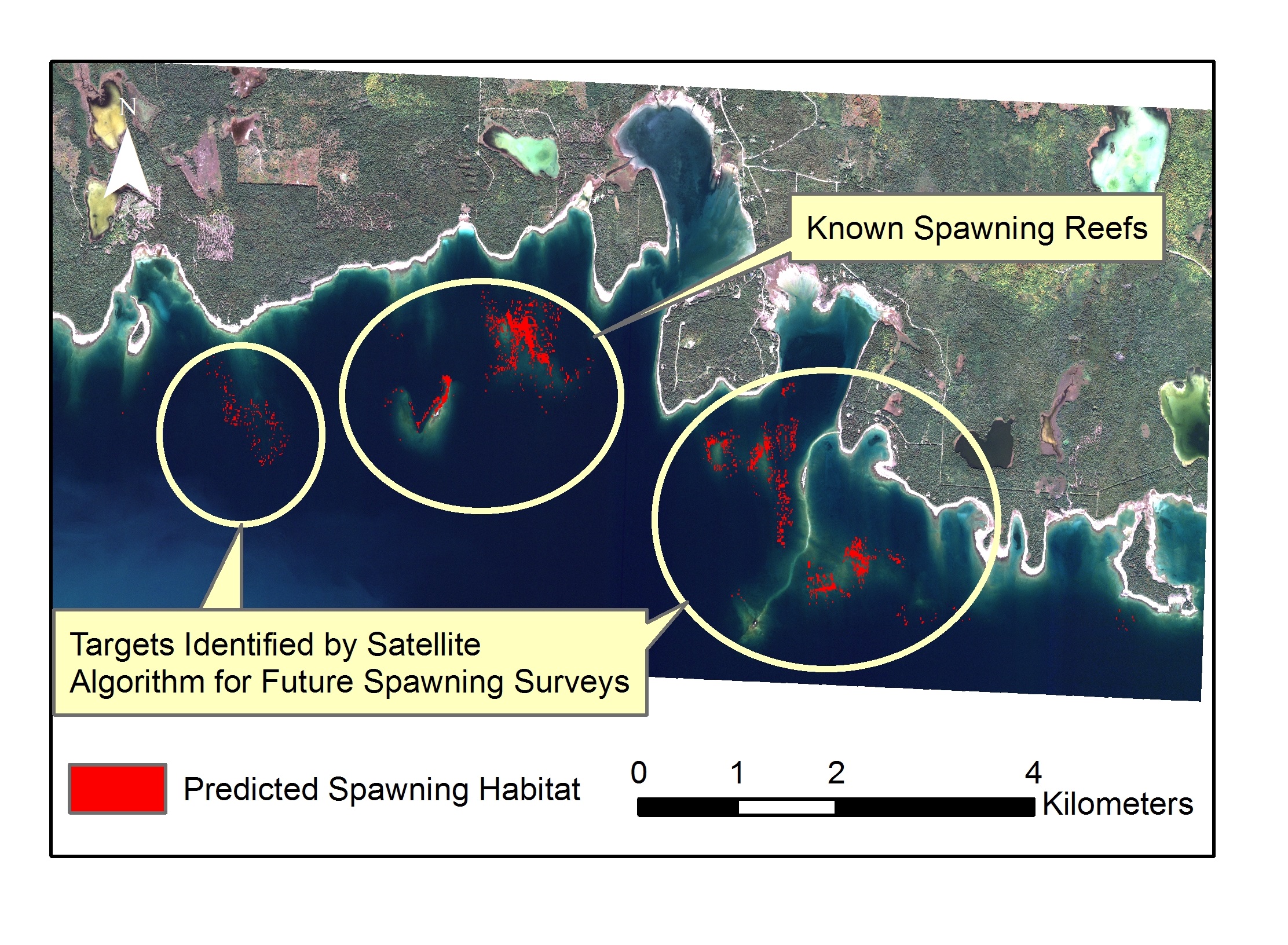

Areas within the Drummond Island Refuge identified by satellites as likely spawning habitat are shown in red. Credit: Michigan Tech Research Institute.

Researchers have been using satellite imagery to look at how the distribution of lake-floor algae in the Great Lakes is changing, said Amanda Grimm, lead author of the study and an assistant research scientist at the Michigan Tech Research Institute in Ann Arbor.

While studying lake trout rehabilitation in the Drummond Island Refuge in northern Lake Huron, U.S. Geological Survey researchers noticed that the stony reefs, where they found lake trout laying eggs, were cleaner of algae than surrounding areas, Grimm said.

They realized the difference might be seen from satellite, which would help find good lake trout spawning grounds.

Satellites scan broad geographic ranges, said Tom Binder, an associate scientist at the Hammond Bay Biological Station and a coauthor of the study. They help avoid labor-intensive searches with divers and underwater cameras.

Grimm said, “It’s not really realistic to physically survey the whole lake when you have a lake the size of Huron. The satellite data really helps us narrow down the likely candidates for where this natural reproduction of lake trout is happening.”

It does that by analyzing how much light is reflected from the lake bottom.

The study began after a project that looked at the physical variables within Drummond Island spawning sites, Grimm said. The researchers already knew where spawning was occurring, allowing them to test the satellite imagery against it. The idea was to confirm that the density of algae indicates higher-quality spawning grounds.

“It seems to work pretty well,” she said. “It’s potentially a useful method for identifying likely spawning areas in other parts of the Great Lakes, especially the clearer lakes, Michigan and Huron. There’s some interest in taking this methodology and applying it to the spawning areas around Beaver Island in Lake Michigan, but that’s not underway yet.”

There are limits. Satellites can only see so far into the water and trout spawn in deeper waters. But since Lake Huron is so clear, the researchers can see the lake bottom to about 40 feet deep, she said.

“The other troublesome part is that lake trout spawn in the fall, which is storm season,” said Steve Farha, a researcher at the Great Lake Science Center in Ann Arbor and a study coauthor. “So it was pretty difficult to get these satellites in the right place at the right time with the right conditions.”

And it’s just a first step.

“It tells you where the probability (of finding spawning sites) is the highest,” Binder said.

Understanding lake trout spawning habitat long-term could help find ways to improve or evaluate hatchery practices, Farha said.

The combination of overfishing and deaths from sea lamprey led to the collapse of lake trout in all the Great Lakes in the 1950s, he said. The Great Lakes Fishery Commission started lake trout restoration in the 1960s, and it is now one of the largest predator recovery endeavors in all of North America.

“It’s sort of unrivaled in terms of scale,” Farha said. “You’re talking 50 years or so of both stocking and sea lamprey control, with the expressed objective of restoring self-sustaining stocks in each of the Great Lakes.”

Sea lamprey are invaders that latch onto fish with a suction cup-like mouth and live off their blood.

Considering the money and effort that’s gone into stocking lake trout for more than 50 years, anything to maximize the probability of bringing the fish back is worthwhile, he said.

Binder said it’s uncertain whether hatchery fish are any good at reproducing in the wild.

If the researchers can determine where spawning sites are, they can study the spawning behavior, he said.

Farha said, “You could imagine that the wild-spawned fish are better at finding the best substrate than hatchery fish are.”

The satellite technique could ease the work in building artificial reefs, he said.

“If we know more about what lake trout use to select habitat, we can build those reefs to suit their needs a little better,” he said.

The researchers are unsure why lake trout spawning grounds are cleaner than the surrounding areas.

“It’s possible that the spawning dislodges a lot of algae and causes the lake bottom to be cleaner,” Grimm said. “But alternatively, it’s also possible that trout are selecting areas where there’s stronger currents and wave action so that their eggs don’t get buried by sediment and debris – and that also results in less algae build-up because the algae is getting fluffed off of the rocks as well.”

According to Binder, lake trout’s preference of cleaner, algae-free spawning sites is key to relying on the satellite imagery. It is as yet unclear if the approach is applicable to other species.

Colleen Otte writes for Great Lakes Echo.