By CLAIRE MOORE

Capital News Service

OWOSSO — In my hometown there’s a little castle upon a picturesque riverbank.

It’s a peculiar sight, really. The old structure stands strong today, its slate peaks and wheatfield-tinted stucco exterior still well maintained even though it’s nearly 100 years old.

The interior is filled with hunting trophies, oil paintings, dusty books and furnishings from a time long past.

One might think the castle belongs in a fantasy novel or in a period film set in Europe, not in the midst of Owosso, a small mid-Michigan city once filled with sawmills.

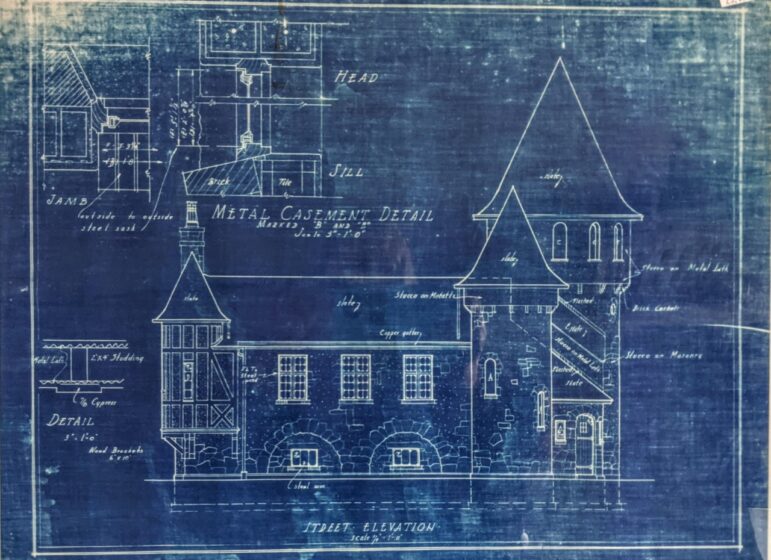

Owosso Historical Commission/Owosso City Museums

A copy of the original blueprint for Curwood’s French-style château castle, which he built in Owosso in 1922.High school students pose before the fieldstone-dotted stucco and in a nearby grove of trees for prom pictures. Couples young and old hold hands and pass by the castle on romantic walks.

Sometimes, a lone angler with a fishing pole or a reader lost in thought can be spotted sitting on the smattering of simple benches that line the riverbank.

I like to think the castle’s original owner, if he were still alive, would be pleased with the reverence the spot receives.

After all, it was he, adventurer and author James Oliver Curwood, who encouraged people to cherish the natural world around them. He was a famous writer in his lifetime, with his stories inspiring dozens of Hollywood films.

This place was home for Curwood, and it’s now home for me. It’s rather unremarkable, cut through by the river called Shiawassee. Curwood is part of its handful of celebrities, including native son Thomas Dewey, the New York governor who lost two presidential races against Franklin Roosevelt, and Rob Oliver, the Emmy-winning animator and director for “The Simpsons.”

Truth be told, I’ve always considered Owosso a sleepy place. But Curwood liked it well enough.

It was in Owosso, partly on the banks of the Shiawassee, where he perfected the wilderness adventure genre.

The city holds an extravagant Main Street parade and festival in his memory each year, but theatrics spread out over a single weekend don’t illuminate the author for all he was.

People with affinities for local history, a love for Curwood’s specialty genre or who have adapted his books into motion pictures remember his legacy.

I recall visiting Curwood’s castle on a school field trip when I was a child, but only faintly. I’ve rediscovered him in adulthood, and a number of his novels will soon be added to the burgeoning book collection on my coffee table.

I was delighted when I found out a young Curwood had tried his hand at reporting. In his early 20s, he studied journalism at the University of Michigan and found work as a reporter in Detroit.

In later years, the Canadian government commissioned him to travel through that country and document his endeavors. His writing, Canadian officials hoped, might bolster tourism.

It was Curwood’s journey through untrodden north Canadian wilderness that sparked his best-known works: His action-adventure books — 33 in total, 28 of them novels — dominated bestseller lists in the 1920s.

They catapulted him to prominence. Set in the Great Northwest and Canadian wildernesses, his novels centered on animal protagonists and were infused with descriptions of the great unknown he’s said to have explored.

It was this proximity to nature that stoked Curwood’s later fixation on conserving wilderness and wildlife.

In his early life, Curwood hunted with devotion. But a hunting trip to the Rockies resulted in an epiphany.

Curwood recalled shooting a bear, but only maimed it. That gave the bear a chance to return the attack.

For some reason, it didn’t. Curwood was astounded.

The encounter changed him. He swore off trophy hunting and adopted a strict adherence to preserving nature.

Streams stocked. Hunting limits. Reforestation. In Michigan, Curwood pushed for all of these things.

In the preface of his 1918 novel “The Grizzly King,” Curwood lamented his history of hunting.

“And that is only one instance of many in which I now regard myself as having been almost a criminal — for killing for the excitement of killing can be little less than murder,” Curwood wrote. “In their small way my animal books are the reparation I am now striving to make, and it has been my earnest desire to make them not only of romantic interest, but reliable in their fact.”

The book was the basis of a 1990 film, “The Bear.”

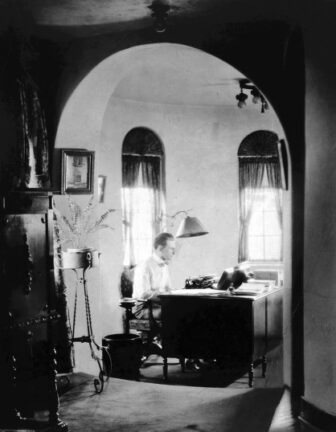

Owosso Historical Commission/Owosso City Museums

Author James Oliver Curwood sits in his writing studio in one of Curwood Castle’s turrets.More reparations came. He donated land and matched funding to build the Shiawassee Conservation Association’s clubhouse.

In 1927, he was appointed to the Michigan Conservation Commission. But Curwood’s hardline, idealistic stance on conservation was “poorly equipped to understand or advance” the early movement’s methodologies, according to James Yates, the author of a 1998 volume of the “Michigan Historical Review” which focused on him.

Curwood’s love of nature ultimately led to his premature demise. He died at 49 in the hot August of 1927. The cause was blood poisoning, thought to be the result of an infected insect bite or sting sustained on a fishing trip.

I find it surprising that unwavering environmental advocates of this modern age haven’t yet elevated Curwood as an icon who refused to relent on his conservationist ideals.

The author lived and breathed idealism, though this is unsurprising — anyone who builds a French-style château to house a quaint writing studio that overlooks a favorite river is, by most accounts, an idealist.

Tours and visits of the castle are open to the public, though it has been closed temporarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic. See owossohistory.org for more information

Claire Moore is a reporter for Great Lakes Echo