By ERIC FREEDMAN

Capital News Service

LANSING – Farm auctions in Southeast Michigan. The trauma of the Flint water crisis. Ice canoe racing in Quebec.

Donovan Hohn has been there, part of what he describes as a preoccupation with “trying to make sense of where we are, where I live, by attending to the natural and the human both, by looking at places where the natural and historic overlap.”

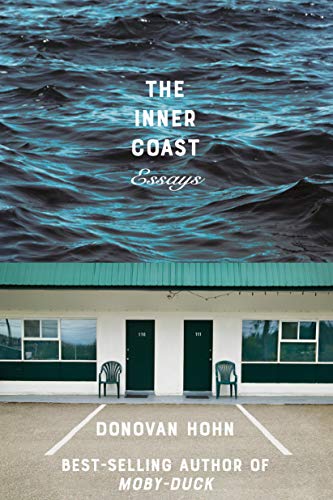

The Ann Arbor writer’s latest effort to find that overlap is a new book of essays, “The Inner Coast” (W.W. Norton, $16.95).

In it, the associate professor of English and coordinator of creative writing at Wayne State University, tells stories in search of that overlap.

“A Romance of Rust,” the opening essay, tells of Tom Friedlander, an Ann Arbor teacher and collector of tens of thousands of wrenches and other “formerly useful things,” many garnered from farm auctions. They’re classified, cataloged, curated, labeled and displayed – although not where the public can see them.

“Old tools are relics of a mythic past, they are also antidotes to automation, standardization, acceleration, infantilization and to the docile brand of utopianism that holds all change to be progress,” writes Hohn, who grew up in California but is descended from generations of Illinois farmers.

In an interview, he said his encounter with Friedlander’s “artifacts of that recent Midwest past” are a way to think of his own “inherited nostalgia.” And writing about the auctions is a way to “honor the other side of the emotion, loss of places,” small farms absorbed into larger operations.

Flint is a different story.

“The Zealot,” a story of the city’s contaminated water crisis, centers on Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech engineering professor whose testing provided evidence both that the water contained dangerous levels of lead and evidence that state and federal officials put expediency ahead of public health. It’s also an account of Edwards’ transformation from neutral scientist to advocate, from “troublemaking outsider” to “authority,” Hohn writes.

He said, “One legacy of that crisis is a corrosion of trust. I was trying to make sense in the essay of how trust can or should be earned.”

And he saw good reasons why Flint residents, mostly African American, mostly low-income, lost trust in government and even in science, saying, “There are dangers to the conferring of authority that comes with the lab coat.”

So what’s that about ice canoe racing?

“Revival of the Ice Canoe” recounts the passions, the dangers and the allures of what Hohn describes as an “obscure sport” with roots in French colonial North America in the 1600s. That’s when missionaries, explorers and fur traders followed water routes from the Atlantic Ocean through the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico.

Hohn had his own dream to follow that entire route himself.

Although that dream was never fulfilled and is now abandoned, he chanced upon the competitive sport that connects to the history of the St. Lawrence River as the terminus of the Great Lakes. The series of annual races includes a competition along an unpredictable and chaotic stretch of river at Quebec City and a comparatively tame event at Montreal.

The race begins,” he writes, “madly, with a cumbersome yet agile dash, a burst of scooting, the teams pushing their canoes across the land-fast ice to the river’s edge, trying to build momentum.

“Heard from the pier,” the essay continues, “the noise of canoes on ice was reminiscent of the sound a skate’s blade makes on ice, or a skateboard’s axle on the curb. Heard from within the canoe, the noise is thunderous.”

Of the athletes who compete, sometimes in the water, sometimes atop the ice floes, he said, “How crazy it is, a really mad thing to do.”