On Monday, Oct. 14, a panel of experts spoke about the political climate in Chile at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum in an panel called “Reclaiming the Streets: Arts of Solidarity in Moments of Crisis.” On Oct. 15, the Michigan State University Museum hosted the event “Envisioning Hope: The Story of The Chilean Arpilleras”.

The panel on Monday included Chilean poet and author Marjorie Agosin, professor Edward Murphy and MSU Museum director Mark Auslander. The panelists discussed the street as a political space to resist oppressive political conditions through artistic expression.

Murphy, who studies Latin America and the Caribbean, said that dictatorships in South America were reactionary and counter-revolutionary to social movements aiming to reclaim the streets.

“When these dictatorships come into power, they implement states of siege, they use the horrific forms of sovereign state power in order to prosecute what they are casting as an internal war,” Murphy said. “This led to massive human rights violations and disappearances, and it led to a systematic panic attack on these groups that sought for revolution.”

Agosin had firsthand experience with the political climate of the authoritarian regime under General Augusto Pinochet from the year 1973 until 1990. The prolific author said the streets under the militaristic regime were filled with fear.

“Latin American societies go outside on the streets, it’s their culture. What the artists were trying to do was disturb the order of the streets,” Agosin said. “It was a battle of reclaiming the streets, reclaiming joy, reclaiming activity and reclaiming sounds.”

Auslander, director of the MSU Museum, said that streets can often be thought of as the most mechanical aspects of modern society.

“Streets and highways are very destructive, but streets can be so much more than that,” Auslander said. “A street is a place where you can interact with fundamentally different categories of people, discover new ways, new forms of selfhood, and new kinds of solidarity.”

Murphy also said that reclaiming the streets meant disrupting the well-established ties the oligarchy had with the United States government, which was engaged with these regimes.

“The idea that it’s just something happening out there that’s foreign is historically inaccurate,” Murphy said. “It’s also a part of our interconnected world and hopefully we can have a better understanding of that.”

This event went hand-in-hand with Marjorie Agosin’s lecture “Envisioning Hope: The Story of The Chilean Arpilleras,” which took place the next day at the MSU Museum.

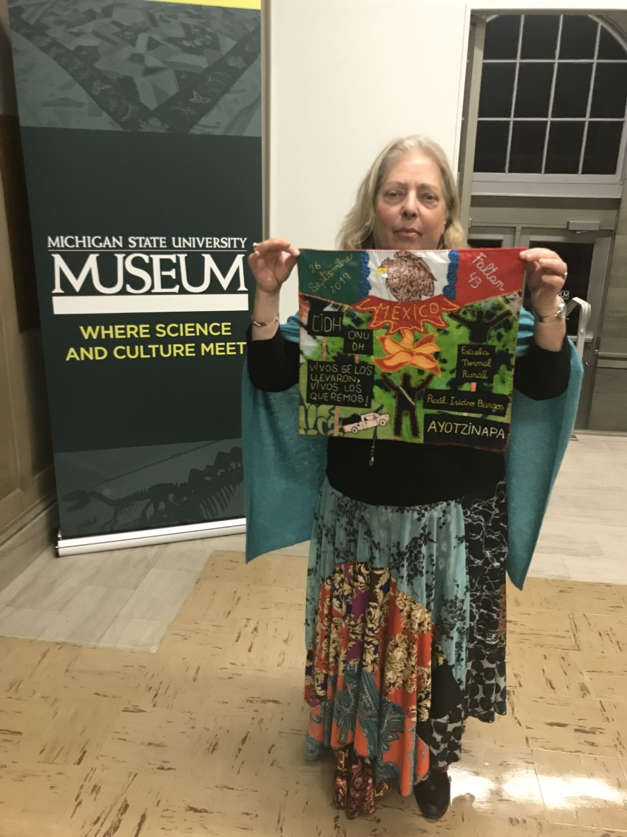

Argosin said arpilleras are pieces of patchwork that tell a story about the life under a dictatorship. The pieces communicated Chilean women’s words about the harsh conditions under Pinochet.

“They (arpilleras) were denouncing the terrible human rights violations that were taking place in the country,” Agosin said. “All of the great revolutions have to tell what happens so that it doesn’t happen again, but unfortunately it always happens again.”

Roxanne J. Frith, photographer and attendee of the Chilean author’s event, was an American foreign exchange student who traveled to Chile in 1976 during Pinochet’s dictatorship.

Frith said that one of her experiences in the South American country as a young photographer changed her understanding of the world.

Alec Reo

Roxanne J. Frith conversing with her friend at the Arpillera exhibit in MSU’s Museum“It was when I was surrounded by machine guns and my camera (was) taken off of my neck and the film stripped out of it because I was photographing a parade. What I was in violation of was photographing military equipment. I didn’t even think about it, it’s a parade,” Frith said. “That was against the law, and as a young 19-year-old U.S citizen, that had not dawnedon me that that could get me shot or put in prison.”