By COURTNEY BOURGOIN

Capital News Service

LANSING — Anti-nuclear groups are identifying the types of transportation needed to haul nuclear waste across the Great Lakes region if a national waste storage site in Nevada wins federal approval.

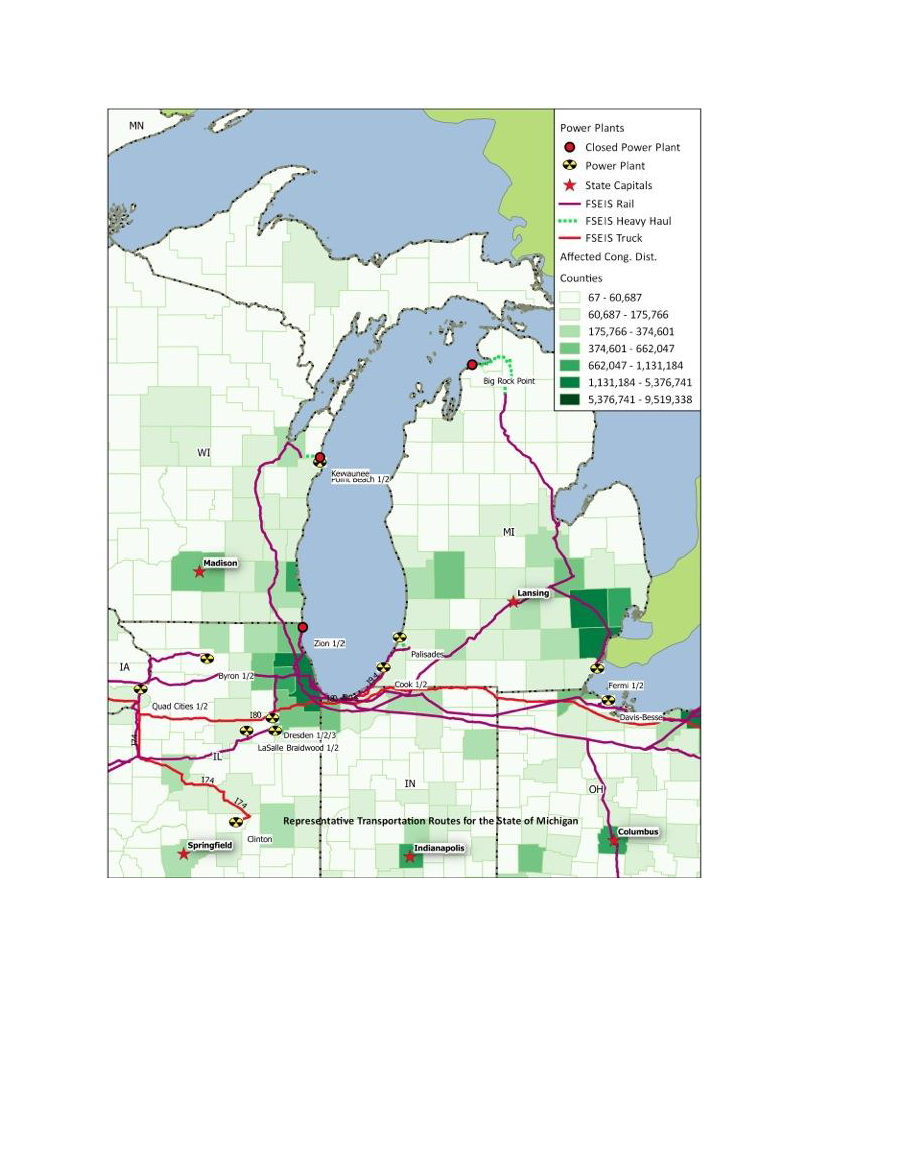

They are adding state-specific details to U.S. Department of Energy maps to show where barges could move waste across Lake Michigan and where trucks and trains could move it across the region.

Beyond Nuclear and Nuclear Information and Resource Service said they wanted to localize a national policy by highlighting truck, rail and water routes necessary to move nuclear waste under a proposed storage policy.

Possible trucking and train routes for nuclear waste in Great Lakes region. Credit: Nuclear Information and Resource Service/ Beyond Nuclear.

For the Great Lakes region, the two anti-nuclear organizations noted multiple places that railways can’t reach and where nuclear waste would instead have to travel across Lake Michigan.

Nationwide, the material would end up at a proposed site at Yucca Mountain in Nevada. There, a potential nuclear repository would lay to rest tens of thousands of tons of radioactive material, said Kevin Kamps of Nuclear Waste Watchdog for Beyond Nuclear, an anti-nuclear advocacy organization based in Maryland.

As many as 453 barges full of used nuclear material could travel across Lake Michigan in total, according to the waterway maps.

Each barge could hold up to 140 tons of waste, according to Nuclear Information and Resource Service. The sheer weight of each container would significantly increase the time necessary to recover spilled nuclear material, Kamps said.

But nuclear energy advocates counter that transporting the waste safely wouldn’t pose a problem.

“This is an incredibly safe process,” said Mitchell Singer, a senior media relations manager at the Nuclear Energy Institute, a Washington-based policy organization that promotes the beneficial uses of nuclear energy.

“Three thousand shipments of used nuclear fuel [have traveled] since 1964 and there’s never been an incident that resulted in a release of radiation from the casks,” Singer said. “There’s no permanent repository for used fuel, but shipments have gone from one plant site to another.”

Still, anti-nuclear groups say they worry about the sheer size of possible shipments, especially when considering the value of the Great Lakes.

“Each container would hold 200 times the long-lasting radioactivity released by the Hiroshima atomic bomb,” according to a Nuclear Information and Resource Service fact sheet.

That number comes from Marvin Resnikoff, a senior associate at Radioactive Waste Management Associates, an environmental consulting company in Vermont that evaluates the safety and economics of radioactive waste management and transportation. His research focused on the possible release of cesium, what Kamps calls a “highly volatile” material within reactors.

Resnikoff found that every pressurized water reactor, like that at the Palisades Nuclear Generating Station in Covert, near South Haven, holds about 10 times the cesium released in the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima, Japan, said Kamps.

“If containers went down in the lakes, water could cause a nuclear chain reaction causing a much greater release,” Kamps said. “If a container breached, it’d be a complete economic shutdown and a rescue would essentially be a suicide mission.”

But Singer says even if a boat went down, containers of waste would remain secure and contained underwater.

“There’s been a long history of safety in these [nuclear waste] casks,” Singer said.

The Yucca repository plan means nuclear waste would travel in heavy-haul trucks in places where railways end. That would present a whole other set of dangers, Kamps said.

The opponents’ Michigan maps show trucking routes from two nuclear power plants- Palisades in Southwest Michigan and Big Rock Point, a closed plant near Charlevoix.

The maps show that Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Illinois would also be required to ship their waste by heavy-haul trucks.

Those trucks must travel up to 30 miles at 3 mph, Kamps said. The catch is that because of their size, the trucks can’t turn. One concern is the risk of breaking wheel axles.

“If these trucks had to stop for any reason during travel, there’s the risk of radioactive exposure to people nearby,” Kamps said.

Singer said that’s not true because the waste would be in secure-enough casks for such problems to never happen.

For now, what Kamp calls “mobile Chernobyl” and “Fukushima freeways” remain on hold. The Obama administration has suspended the budget for the Yucca Mountain repository project. In addition, the administration denied the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and Department of Energy budget request to further review the site.

“The administration made our position clear—Yucca Mountain is not a workable solution,” said Bart Jackson, an Energy Department public affairs official. “The administration supports working with Congress to develop a process that is transparent, adaptive and technically sound.”

But the tides might change with next year’s presidential election.

For Singer, the safest place is Yucca. Its arid nature makes it the most effective place for storage, he said.

Singer said he hopes a new administration will renew the Yucca proposal since no “showstoppers” have definitively shown potential dangers.

Kamps said anti-nuclear groups created the maps to make the public aware of the plan’s health and safety risks. But the only way to protect public health is by keeping waste in dry and secure

Courtney Bourgoin writes for Great Lakes Echo.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR CNS EDITORS

Nuclear Information and Resource Service maps: http://www.nirs.org/radwaste/hlwtransport/mobilechernobyl.htm.