By COLLEEN OTTE

Capital News Service

LANSING — A stretch of lakefront. Expanses of forest on either side. Abundant wildlife.

These are characteristics that most people view as ideal for a family cottage or a retirement home.

They are formally known as the wildland-urban interface and are detailed in a recently U.S. Forest Service publication.

“The atlas brings together maps of the whole U.S. and each of the states that show where the wildland-urban interface is,” said Susan Stewart, one of the book’s authors and a staff scientist at the University of Wisconsin.

It shows where housing and wildlife vegetation coincide. Housing includes individual homes, apartments and condominiums. Wildlife vegetation encompasses forest, grassland, shrub land, wetland and any vegetation that is not agriculture or otherwise human-planted.

Credit: Colleen Otte

“There’s room for people where they’ve been living,” said Richelle Winkler, an associate professor of sociology and demography at Michigan Tech University. “It has more to do with our preferences.”

Both Winkler and Stewart said many states in the Great Lakes region struggle to expand their populations. Michigan lost population between 2000 and 2010.

“But that’s never the whole story because the other thing rural demographers look at is the redistribution of population,” Stewart said. “The changes on the landscape are a result of people moving from one place to another.”

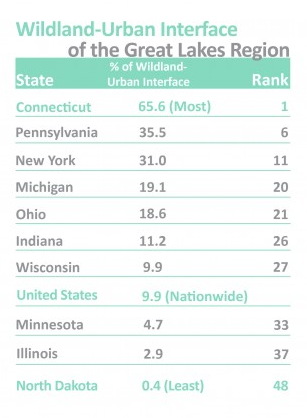

Of Michigan’s total area, nearly 20 percent is classified as wildland-urban interface areas.

In Michigan and other Great Lakes states, that’s mostly due to seasonal homes often at the wildland-urban interface, Stewart said. They attract people looking for vacation or retirement homes.

Because there’s a cultural ideal about “retiring to the lake,” the interface is more influenced by the age of the state’s population than total population, Winkler said. Many baby boomers reaching their retirement years have been considering — if not already building — a second home.

“They’re not trying to choose a home in a place where the commute is easy, and they’re not concerned about schools for their kids,” Stewart said, “so they choose a home based on where they want to live — and people like to live close to nature.”

Such areas are “natural amenity destinations” because their scenic beauty and outdoor recreation attract people, Winkler said.

Other cultural concepts play into growth of the urban-wildland intersection, Winkler said.

“We have this dream about a single-family home with a yard and space,” she said, “and if we all want to live like that, then we’re going to keep expanding into the interface.”

Demographers have noticed that especially in Michigan and other Rust Belt states with older cities, growth typically occurs on the fringes of cities in the form of urban sprawl, Stewart said.

In cities like Detroit, growth manifests itself in the suburbs and beyond.

Winkler said, “They become doughnut-like where the growth is really around the edges and pushing farther into the countryside. In our region, it’s kind of divided north-to-south in the states, especially if you’re talking about Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan.”

In these states, expansion in the north is driven by seasonal and lake home development. Southern growth is primarily a result of larger urban populations building along the outskirts of town, she said.

The intersection of wildlands and urban landscapes is expected to grow.

Stewart said, “The rate of housing growth has been faster than the rate of population growth since about the 1940s because of changes in society, including smaller family sizes, fewer multi-generational homes, more single households and single-parent households.”

And seasonal homes have increased as people have more vacations and time and good health at the end of life.

With population increases come even greater housing increases and pressure for building sites, with accessibility and technology driving these types of growth.

For example, roads make remote areas more accessible, and “the ability to work from a virtual office tends to encourage wildland-interface growth,” she said. “When people are not tied to an office location, locating where there’s nice scenery and lots of things to do outside gets people into the wildland-urban interface.”

The study began as a way to track seasonal home growth in resort areas, Stewart said. However, the work became important to fire management agencies working to reduce fire hazards near houses.

“When you want to do that, you need to know two things: where the vegetation is and where the houses are,” Stewart said.

The Great Lakes region’s wildfire threats are less extensive than those in the West, she said. The Huron National Forest in Michigan’s northeastern Lower Peninsula, the eastern end of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, the Wisconsin sand barrens, and areas in northern Minnesota have all burned.

“Of course, it’s not that common here. But there are these little pockets, and sometimes those are a real concern because the states don’t live in this constant fear of wildfire,” Stewart said. “It’s only these small places, so people tend not to be very aware of it.”

The interface has significance for far more than firefighting here because it shows where people and nature overlap and interact daily, she said.

And while some species, like raccoons, skunks and crows, are relatively happy living around people, other birds and mammals avoid human activity. Animals like wolves don’t do well in fragmented forests, she said.

These animals can cause problems, as when bears dig through Dumpsters or raid campsites.

Pets at the interface also pose concerns, Stewart said. For example, cats kill birds and dogs disturb ground-nesting birds when they run free and sniff around the forest floor.

Another concern is landscaping. Homeowners may water and fertilize their yards and often plant non-native species. New species and additional nutrients are a dangerous combination for introducing invasives that can significantly alter an ecosystem. Another bad habit is dumping yard waste in the nearby forest.

“One doesn’t have to be an ecologist to understand that you’re probably introducing things into the forest that weren’t there before your house was there,” Stewart said.

Colleen Otte writes for Great Lakes Echo

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR CNS EDITORS

The 2010 Wildland-Urban Interface of the Conterminous United States: http://www.fs.fed.us/nrs/pubs/rmap/rmap_nrs8.pdf