By JENNA CHAPMAN

Capital News Service

LANSING – The Michigan State University Museum has discovered something it didn’t know it

possessed – a full skeleton of a passenger pigeon.

Visitors can even touch the rare skeleton of the now-extinct bird – in a digital form, said exhibit

curator Pamela Rasmussen. Viewers can enlarge and rotate the image of the skeleton on a touch

screen.

Mounted specimens of passenger pigeons on exhibit: Credit: Pearl Wong, MSU Museum

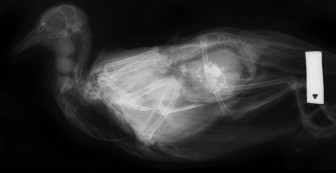

The real skeleton is in a stuffed skin in the museum. It was found while researchers from the

museum worked with the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine to take computed tomography

scans of passenger pigeons to measure their bones.

This is a rare occurrence, for most stuffed skins have few bones in them, Rasmussen said. The

discovery was especially surprising because the bird has been extinct for so long – a full century.

The scans are part of a new exhibit, “They Passed Like a Cloud: Extinction and the Passenger

Pigeon,” that includes 3D models of passenger pigeons, fossils of other extinct species and

success stories where species in danger of extinction were saved.

Researchers discovered this full skeleton of a passenger pigeon in a stuffed skin. Credit: Pamela Rasmussen, MSU Museum

The once-abundant pigeons used to nest in flocks of up to a billion birds around the Great Lakes

region. The last large flock was reported in Petoskey in 1878.

Chief Pokagon, last chief of the Michigan Potawatomi people, reportedly described this scene

in 1850: “I was startled by hearing a gurgling, rumbling sound, as though an army of horses

laden with sleigh bells was advancing through the deep forest. I beheld moving toward me in an

unbroken front millions of pigeons. They passed like a cloud through the branches of the high

trees, through the underbrush and over the ground.”

The birds went extinct 100 years ago after people began hunting the giant flocks.

The last known survivor named Martha died in August 1914 at the Cincinnati Zoo. Her mounted

body is at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

“I hope that people will recognize our impacts and think, ‘What can we do to have less sad

stories?’” Rasmussen said.

The MSU museum exhibit runs until Jan. 25.

“We lost an opportunity for restoration down the road that we can’t get back,” said Patrick

Rusz, director of wildlife programs at the Michigan Wildlife Conservancy in Bath, said of the

passenger pigeon.

Rusz said that the problem of extinction as a whole relates in part to lack of information.

“Sometimes people think animals are simply dwindling when they are actually gone, and

sometimes people think they are gone when they aren’t,” he said.