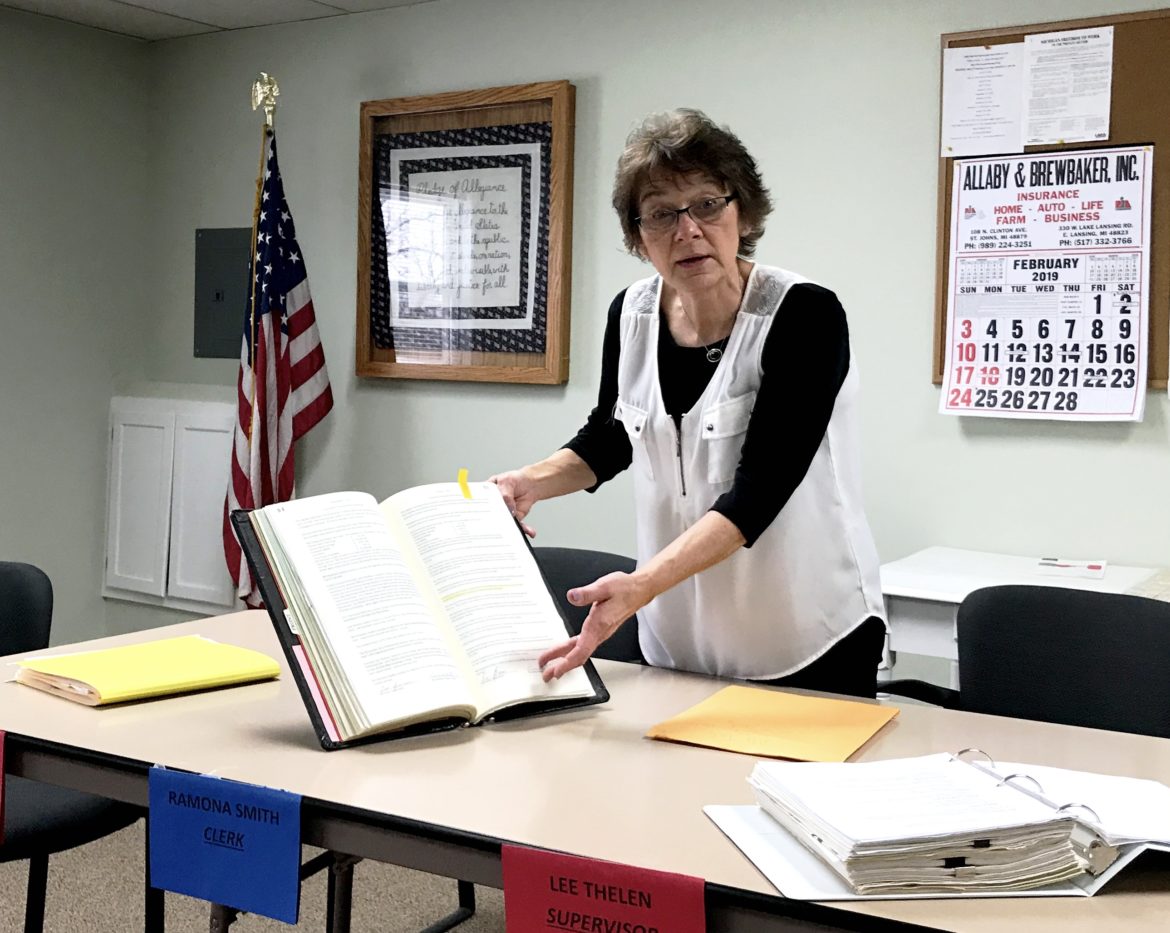

Ramona Smith was a trustee for Greenbush Township in rural Clinton County, just north of Lansing, when she became concerned with a lack of transparency in the township’s government.

So she decided to run for clerk.

In 2016, Smith and four other township candidates won office on a shared platform of transparency.

“We were having many conflicts in this township, and that was our main goal: Our residents would know when we were spending their money and how we were spending their money,” she said. “Anything they wanted to know, we were open to that.”

That’s the guiding principal behind Michigan’s Freedom of Information Act, a 1976 law that requires most local and state governmental entities to provide public access to their records. But local governments often have different resources to respond to such requests by citizens.

Students in four classes in the Michigan State University School of Journalism, working together for the Spartan Newsroom, filed public records requests with most of the 79 cities and townships in Clinton, Eaton and Ingham counties — as well as the counties themselves. The requests sought logs of all public records requests received in 2018.

Smaller, more rural communities — where the local government often is run directly by elected officials with few, if any, full-time government employees — were less likely to keep formal logs than local governments in more urban areas, the project found.

[infogram id=”6909480f-95f3-4d1e-8af2-1625b37ecdf3″ prefix=”5yE” format=”interactive” title=”FOI Requests”]

Range of records

Requests made to local governments in 2018 under the state public records law, often referred to as FOI or FOIA, ranged widely, from a copy of the emergency response plan for Potterville’s water supply system, to property records in Lansing, to employee compensation information in St. Johns.

In general, anyone can request any government document and, barring certain exemptions, they’ll receive it. There are about 25 specific exemptions to the state’s FOIA that give public officials the right to keep some types of records secret.

Not surprisingly, more urban and populous municipalities in the area received more FOIA requests in 2018, Spartan Newsroom’s research shows.

Some smaller local governments might not even receive a single request in a year. East Lansing, the area’s second largest city, received 147 public records requests. In comparison, Greenbush Township with a population 2,200, has received two requests since Smith became township clerk in 2016.

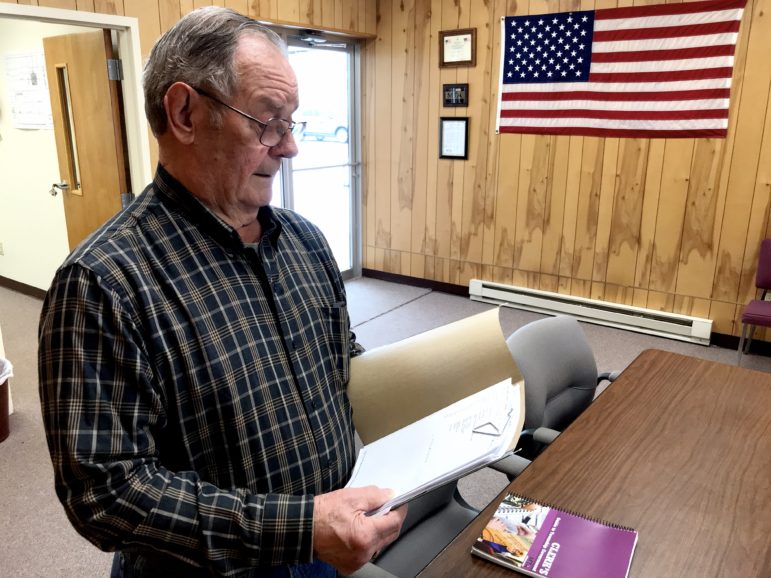

Ten minutes east in Clinton County, Duplain Township, population 2,400, received three public records requests last year.

“Because we’re a small town, it doesn’t make us any less important,” Duplain Township Clerk Richard Bates said.

More development, more records

One factor driving the disparity in the number of public records requests received in urban and rural communities is the differing amounts of development. More development often means more requests.

A majority of East Lansing’s 2018 records requests dealt with planning and development issues.

East Lansing is home to about 48,000 residents and Michigan State University, with its student population of more than 50,000. Housing and retail developments surround the campus.

In Delta Township in Eaton County, which has 33,000 residents and received 81 public records requests in 2018, property transfers are among the most requested records, said township Supervisor Brian Reed, who serves as the local government’s Freedom of Information Act coordinator.

It took Delta Township four days to fulfill the FOIA request for its FOIA log.

Kurt Williams

Duplain Township Clerk Richard Bates says he’s a recognizable and approachable figure when he walks around downtown Elsie in Clinton County. It’s from these kinds of information conversations that he says citizens often get information about their local government.

‘Transparency is very important’

Another factor driving the difference in FOIA request numbers is how government-public interactions happen in smaller towns, Michigan Press Association General Counsel Robin Luce Herrmann said.

Herrmann says residents in smaller towns may not have to file formal requests to get the information they need. In these communities, citizens may have a personal relationship with their government officials or residents may find it easier to personally visit government offices and make a verbal request. Verbal requests generally wouldn’t be logged by local officials because state law requires formal records requests made under FOIA to be in writing.

Speaking from experience, Bates agrees.

“I feel that all politics are local, and we’re not much different out here. We just have small issues,” Bates said. “The local people hardly ever file a FOIA because they know they can come to the township meeting or stop you on the street.”

State and local governments have five days to respond to a public records request, although processors can request a 10-day extension if needed.

Even with a large number of requests, East Lansing City Clerk Jennifer Shuster said she likes to avoid the 10-day extension because she wants to get the information to the requester as quickly as possible.

It took East Lansing three hours to fulfill Spartan Newsroom’s request for its log of public records requests received in 2018. City officials received 147 requests, excluding requests to the city’s police department.

“I believe transparency is very important to the city of East Lansing and that is why it becomes a high priority to us when we do receive a FOIA request,” Shuster said.

Kurt Williams

Richard Bates, clerk for Duplain Township, relies on his Michigan Township FOIA handbook to help him fulfill public records requests. He said Duplain receives on average two requests a year.

Delays and violations

Failure to grant or deny a request within five days is one of the most common violations of the Freedom of Information Act. For small communities, the problem can be a lack of awareness or misunderstanding of the law, Herrmann said.

The public records law was most recently updated in 2015, and some communities have been slow to adapt — although resources are available.

Bates said he relies heavily on his copy of the Michigan Township Association handbook of public records guidelines. The handbook is “worth its weight in gold,” he said.

Bates responded within hours to the request for the township’s 2018 public records log; there were two.

For Hermann, in the same way public officials must understand necessary financial statements, they must understand FOIA. It’s too critical of a service for public officials to ignore, she said.

Michigan Municipal League, Michigan State Extension and Michigan Association of School Boards also offer training and resources on freedom of information requirements, she said.

If those avenues fail, there’s the law itself.

“The Freedom of Information Act is pretty easy to read and understand,” Herrmann said.

Creating a process

Smith, who is the FOIA coordinator in Greenbush Township, she said the process of fulfilling requests can be daunting, even for a small township with a population of about 2,200.

Greenbush initially failed to provide the township’s public records log in an emailed request, but had a followup conversation with a Spartan Newsroom reporter about how many requests the township received.

Before 2013, the township didn’t even have a FOIA procedure, so the Greenbush government is still learning. Smith approached the Michigan Township Association for advice.

“The MTA asked: Do you have a FOIA form?” Smith said.

The township didn’t have a form, a process for handling FOIA request, or a lawyer to help establish either, so township officials went out and got a lawyer and put a procedure in place.

It’s this kind of effort Hermann says even the smallest governments need to do so they can stay compliant with the law and be responsive to citizens.

Having a system in place can also help local officials if they receive a more challenging request. Last year, Greenbush Township was among many local governments across the state that received a request for 2016 election information. Most of those requests were made by someone identified only as “Emily” from an organization called United Impact Group.

The effort was later connected to a voting rights nonprofit affiliated with a Democratic super political action committee, but the mysterious nature of the request put many local officials on edge.

“FOIAs are quite complicated,” Smith said. “I was quite comfortable with our own township ones.”

She’s less comfortable with large requests from non-local requesters.

“That’s quite a bigger concern because it’s something legally you have to do.”