By JOSH BENDER

Capital News Service

LANSING — James Atkinson’s art draws inspiration from a plethora of microscopic life found in a single drop of pond water.

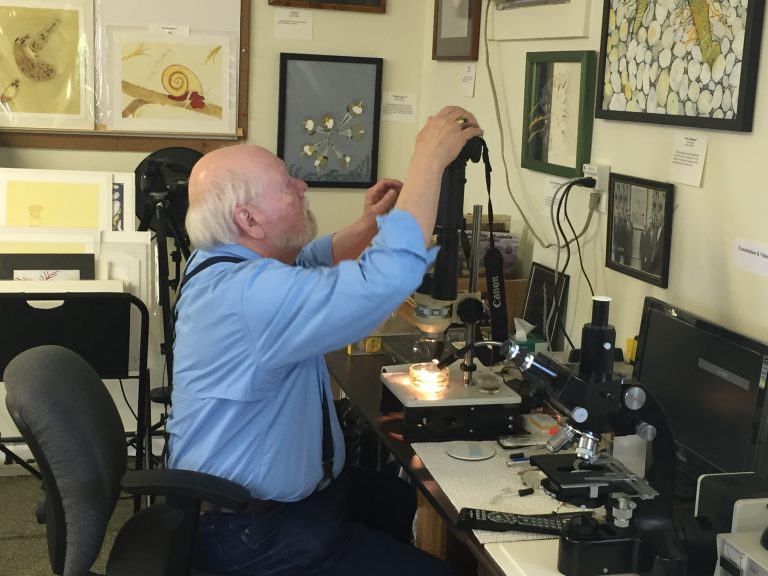

The St. Clair County artist paints from still images taken from videos of organisms that the retired zoologist shoots through a microscope. Filming the critters began as a way to engage students during his teaching career at Michigan State University.

Painting came toward the end of his 43-year academic career, he said. “I wanted to get people in general to realize how beautiful these creatures are, so I decided to start painting.”

Artist James Atkinson prepares to video microscopic organisms. Credit: Josh Bender

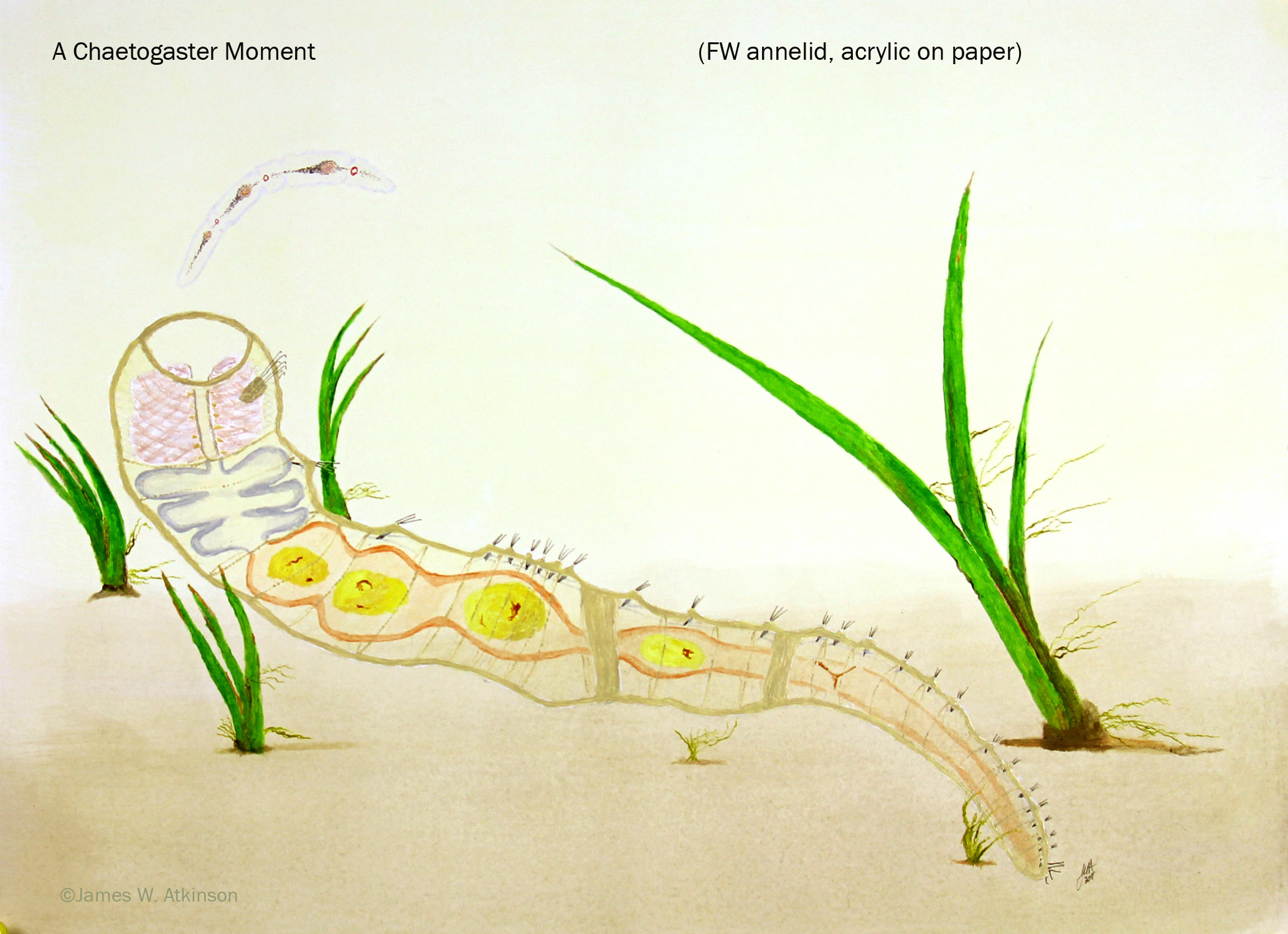

Capturing microscopic fauna in a way that shows their relationship to the larger environment requires a keen eye that blends scientific and artistic skills, he said.

“You have to note all the nuances,” he said. “An artist who wants to do this kind of art can’t just glance, and I think a scientist working at a microscope has to do the same.

“It’s a matter of trying to understand an experience.”

In one painting, an unidentified rhabdocoel flatworm is eating, and an unidentified annelid, a segmented worm, is being eaten. It’s based on an event in a culture dish witnessed through the microscope. The animals were collected from Hewes Lake in the Dansville State Game Area in Ingham County.

Part of the intrigue and challenge of painting and studying microscopic aquatic life is that people don’t understand much about it, he said. “There are so many ponds, lakes and wetlands – big and small – that nobody has ever looked in.”

It’s difficult to estimate the size of populations, and there are potentially many undiscovered species of microscopic life lurking in lakes, ponds and streams, he said. A scientist looking for a species could take 50 samples from the same lake and find a member of it only once.

“They are worse than needles in haystacks,” he said.

Chaetogaster is a segmented worm that preys on water fleas and, as depicted here, a flatworm. It’s common in lakes and ponds throughout Michigan, including the Shiawassee National Wildlife Refuge. Credit: James Atkinson

Atkinson’s wife, Elizabeth, often travels with him around Michigan as he samples bodies of water. She’s impressed with what he finds

“These marvelous, intricate creatures are an important part of the food web,” she said.

At a recent showing in his home studio, about a dozen relatives, friends and neighbors gathered to admire his work.

Violence stands out in some paintings of organisms consuming one another, said Charlie Lewis, Atkinson’s son-in-law. He sees a similarity with what he observes daily without a microscope.

The microscopic food cycle is reminiscent of dairy farming, said Lewis, a farmer. Corn is grown to feed cattle that produce manure to fertilize new corn to feed more cattle.

“Everything eats everything else,” he said.

The complexity of the organisms in the paintings is startling, said Gary Moore, a family friend. “It’s another world.”

The 74-year-old Atkinson who retired in 2011, moved with his wife to North Street roughly a year ago to be near their children and grandchildren.

There, in the midst of the farmland, he set up his art studio.

It houses an eclectic mix of scientific equipment and art supplies. The walls are covered with paintings. Towards the back stands a microscope, video camera and computer monitor for capturing microscopic fauna in action.

Nearby are water tanks housing snails smaller than a thumbnail and other life forms that inspire Atkinson’s art.

The coldly utilitarian design of the scientific equipment and tanks contrast starkly with the vibrant paintings they inspire.

He maintains one saltwater tank for marine life to inspire his work when he cannot collect freshwater samples during the cold Michigan winters.

A Welsh flag hangs in the corner as an homage to his maternal ancestry. Atop a bookshelf is a bust of 19th century Hungarian virtuoso pianist and composer Franz Liszt.

Though a classical music fan, Atkinson isn’t big on Liszt. The bust was bought at a flea market to serve as model for improving his drawing technique.

Many of the older paintings feature organisms taken from a pond at his former home in Mason, he said. Others feature the life found in ponds on MSU’s campus.

One of his favorites is of the carnivorous rosy wolf snail because of the story of how it spread.

The snail was introduced to control the giant African snail, which had become a pest as a result of its widespread use across the Pacific for food and as an aphrodisiac, he said.

Rosy wolf snails are a third to half the size of the giant African snails, but the eradication method worked – perhaps a little too well. In Hawaii, many native snails are now endangered because of the rosy wolf snail’s voracious appetite, he said.

The paintings are more than a hobby. They’re meant to help people who lack a powerful microscope further appreciate the richness and diversity of the world around them, he said.

Even the painting of the destructive rosy wolf snail is meant to teach a lesson: “Don’t introduce a biological control unless you really know what it’s going to do.”

Atkinson’s paintings are sold online and on consignment in some Michigan galleries, though the artwork is mostly a labor of love, he said. Originals costing roughly $300 to $500 are available on his website site, while prints cost around $30 to $50.

Josh Bender writes for Great Lakes Echo.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR CNS EDITORS

JW Atkinson Art: http://www.jwatkinsonart.com/index.php