By MICHAEL KRANSZ

Capital News Service

LANSING — In portions of the northern Lower Peninsula next year, farmers in need of relief from hungry deer and hunters in search of turf might mutually benefit from an expanded state land-access initiative.

The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) initiative, called the Hunting Access Program, would open more private land to hunters in the northern Lower Peninsula with a new federal grant of nearly $1 million.

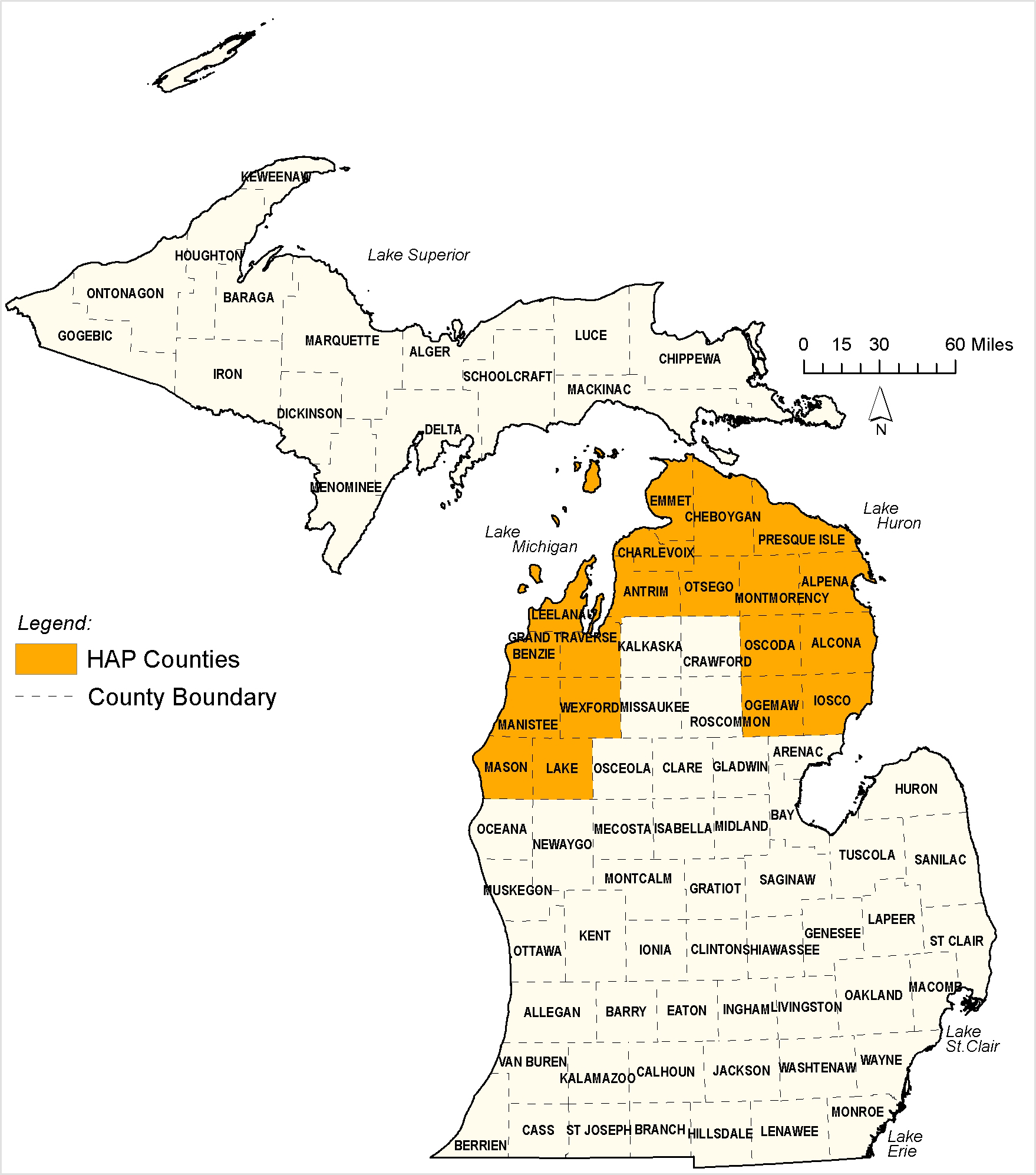

Counties: Mason, Lake, Manistee, Wexford, Benzie, Grand Traverse, Leelanau, Antrim, Charlevoix, Otsego, Emmet, Cheboygan, Presque Isle, Montmorency, Alpena, Oscoda, Alcona, Ogemaw and Iosco.

Map courtesy of the Department of Natural Resources

Among the counties included are Alcona, Montmorency, Emmet, Cheboygan, Antrim, Leelanau, Grand Traverse, Manistee, Mason, Lake and Wexford.

Currently, only landowners in Southern Michigan, mid-Michigan and the eastern Upper Peninsula who want to be paid to open their property for hunting are eligible, said Mike Parker, the DNR biologist spearheading the program.

Landowners set restrictions on the type of hunting and can earn up to $25 per acre, depending on the type of hunting allowed and habitat quality, according to DNR.

Most lands currently enrolled allow all types of game hunting, with the exception of the eastern U.P., where hunts are restricted to sharp-tailed grouse and small game.

The principle of the initiative, dating back to 1977, has been to expand hunting access in parts of the state with little public game areas, Parker said.

“Research shows that if people don’t have a place to hunt that’s relatively close to home, they just don’t hunt,” Parker said. “Hunting participation has been declining for several years. It’s a slow decline, but any decline is alarming.”

But what’s unique about the expansion into the northern Lower Peninsula is the intersection of that founding principle with wildlife management objectives: on the west side to mitigate deer damage to orchards, and on the east side to further cull the herd that harbors bovine tuberculosis, Parker said.

Jim King, owner of King Orchards, estimated that each year he might lose 10 to 15 percent of his crop of peaches, apples and cherries to deer.

“We cannot grow fruit trees without a fence, and it’s not that they eat the fruit — they eat the buds that will be next year’s fruit, and they eat everything from knee high to 5 feet in the air,” said King, whose orchards are in Central Lake and Kewadin in Antrim County.

Bucks also cause devastation to younger trees. One year King planted 40 trees that never made it to maturity because a buck came through and rubbed its antlers on all of them, destroying them, he said.

Many in King’s family hunt. With most of their land allocated to fruit production and to avoid the high cost of buying more land for hunting, they used to hunt in the orchard, King said.

But the irony, he said, is what they realized after starting to install an 8-foot tall fence around their orchards 20 years ago:

“Once we put up our fence, we realized that with the cost of our fence and with the amount of losses we had over 30 years, we could have easily purchased hunting ground,” he said with a laugh.

On the east side of the northern Lower Peninsula, deer present another problem to farmers: They’re reservoirs for bovine tuberculosis.

If the disease spreads to cattle, it renders them unfit for use, said Rick Smith, the bovine tuberculosis program manager for the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

While eradication of the bacteria in the white-tailed deer population is nearly impossible in Alcona, Montmorency, Alpena and Oscoda counties — where the majority of infected deer dwell — the estimated proportion of infected deer has dwindled from 5 percent 20 years ago to 1 percent, said Steve Schmitt, a DNR wildlife veterinarian.

But that small fraction of the deer population shouldn’t deter hunters looking to eat game, said Schmitt, who studies bovine tuberculosis in deer.

“We’ve had tens of thousands of hunters in that area and no hunter, as far as we know, has become infected from eating the meat,” he said.

The bacteria is found primarily in lung lesions. And the only reported case of a hunter contracting the disease was when he poked the lesions and then poked himself with the same knife, Schmitt said.

The acreage covered by the Hunting Access Program in Michigan has tripled in the last five years — thanks in large part to grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Parker said.

In 2010, the program enrolled 47 farms and nearly 7,400 acres. In 2014, those numbers increased to 153 farms and 17,353 acres, he said.

One of the most recent additions was the easternmost U.P., around Chippewa County, last year. The area is known for its sharp-tailed grouse population, which is found primarily on private land, he said.

Unlike the Lower Peninsula areas, hunters on land in the program in the new U.P. region can hunt only sharp-tailed grouse and small game.

To locate enrolled private lands or get information on how to enroll your land, visit michigan.gov/hap.