By SHEILA SCHIMPF

Capital News Service

LANSING – The idea of graveyard as park, with landscaping designed to aid contemplation and to encourage the illusion that the visitor had left the regular world behind, is a surprisingly modern one.

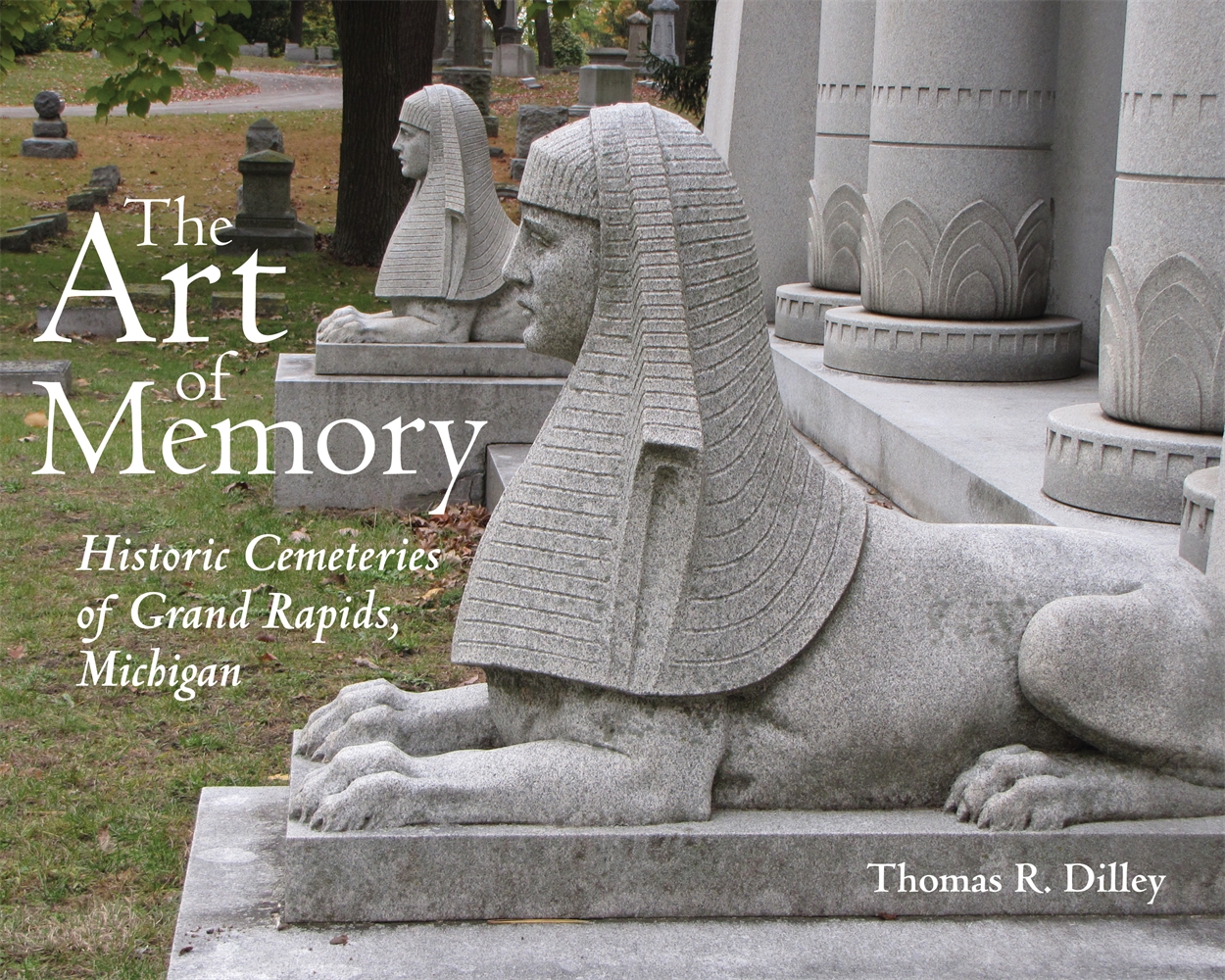

In fact, in this country it goes back only to the 1830s, says Thomas Dilley, author of “The Art of Memory: Historic Cemeteries of Grand Rapids, Michigan,” a new book published by Wayne State University Press ($39.99).

The Art of Memory: Historic Cemeteries of Grand Rapids, Michigan by Thomas Dilley

Before the 1830s, graves were in or near churches, clustered in tight places. But then, as churches ran out of room, cities dedicated large empty tracts, either within the city or just outside, as burial places. The vacant space had to be structured for the dead and the living who came to bury and visit them.

“There are parts of the cemeteries that were designed to allow peacefulness,” Dilley said. “These parts are near the center of the cemetery. They are landscaped in a way that street noise and the consciousness of what lies beyond the cemetery is more or less erased. The way it is laid out encourages rambling through this area.”

Dilley is a frequent cemetery rambler. He has led 7,000 to 8,000 people through Grand Rapids cemeteries in the past.

“These people are not there to look at their own families,” he said. “They are there to look at the markers.”

The markers are worth looking at. Dilley’s book has 236 photos of lambs, angels, symbols, buildings, words, sculptures all designed to remember the dead, honor their memory and—possibly—impress the neighbors.

Fulton Street Cemetery, the first dedicated cemetery in Grand Rapids, dating from 1838, includes a 5-foot- tall granite boulder with the names of John and Mary Ball inscribed on it. The Balls, who died in 1883 and 1884, gave the city the land for a large park. The boulder was removed from that land and used as their grave monument.

Dilley admits to getting hooked on cemeteries and stories like the Balls’ as a 10-year-old growing up Grand Rapids when his bus drove past Oak Hill Cemetery and he caught sight of a pyramid. The idea of a pyramid in Grand Rapids intrigued him. In truth, the retired attorney still gets excited talking about something equally as Egyptian: obelisks.

“Obelisks are the oldest form of memorial in this country,” he said. And, he said, putting an obelisk into a cemetery in Grand Rapids in the 19th century was not much easier than erecting one in ancient Egypt.

Some obelisks in Grand Rapids cemeteries can be 50 feet tall, weighing 20 or 30 tons. Once the railroads came to Grand Rapids, a granite obelisk could be shipped from Vermont or New Hampshire, but when it got there, it still had to be removed from the train, transported to the cemetery and raised from a horizontal to a vertical position.

“Many pieces of stone fell apart at that point,” he said. “They fracture. That’s why they were so expensive.”

Choosing, designing and creating monuments required a large infrastructure of undertakers, artists and stone suppliers. It didn’t come cheap but family members had their eye on the future. “They wanted something that would make a statement,” Dilley said. Vanity was part of it, but the most elaborate monuments strove for timelessness.

Many of the markers stand over three generations of a family, a custom Dilley sees declining as cremation and mobility erode that possibility.

Dilley’s book includes short stories about the people named on the markers in photos, explaining how they affected Grand Rapids history. Dilley is a member of the Grand Rapids Historical Commission and a trustee of the Grand Rapids Historical Society.

“In my wanderings,” Dilley wrote in the preface to his book, “I have found incontrovertible evidence that these cemeteries are not just places where the dead rest—they are spaces where generations of those who have come before us speak to us, if we will only take the time and expend the efforts to listen.”

Other areas in Michigan have equally old or interesting cemeteries, Dilley said. They are found in areas that used to be thriving, prosperous centers of a business such as mining or lumber, such as the western U.P.

Marquette, for example, has graves that go back to at least the 1860s, said Beth Gruber, assistant librarian at the John M. Longyear Research Library in Marquette. The last half of the 19th century was a time of creative and significant monuments.

“Park Cemetery has some very ornate ones,” she said, citing the Kaufman mausoleum designed as a reproduction of the Parthenon.

The Marquette Regional History Center does community tours once a twice a year, including a “tombstone detectives” tour for grades 1-8.

In Detroit, Elmwood Cemetery offers tours of famous graves including Territorial Gov. Lewis Cass, Underground Railroad superintendent George DeBaptiste and Mayor Marshall Chapin.

Elmwood goes back to 1846, according to the Historic Elmwood Foundation. It was redesigned into a park in 1890 by Frederick Law Olmsted, best known for designing New York City’s Central Park.

Dilley and Gruber both say touring cemeteries is best done in warmer weather. Dilley’s favorite season is early fall. Tours at all three cemeteries end in October, starting up again in the spring. Tours can be arranged by calling the local historical society.

Resources for CNS editors:

In Grand Rapids, http://www.grhistory.org

In Marquette, http://www.marquettecohistory.org/

In Detroit, http://www.elmwoodhistoriccemetery.org